Chapter 10 (Part 5): Financial Freedom in Medieval Islam

The Abbasid Caliphate (AD 750 - 1258) has a two-tiered financial economy. The military machine tied the government to land taxation while the merchants developed credit arrangements based on trust.

If you are new here, we are reading David Graeber’s Debt: The First 5,000 Years. Catch up and join us on Thursdays in 2024. My first slow read here on Substack in 2023 was David Graeber’s The Dawn of Everything. These two books showcase his thesis on the development of humanity by looking at how debt evolved and how people organised themselves and their world. Unique among his peers, Graeber still asks the big questions in anthropology.

Dear Reader,

We shall take a break for Christmas and Boxing Day (26th) next week! Enjoy your festivities!

I’m looking forward to cooking two dishes that I have now assigned as holiday meals. Since I experimented last year — ox tongue braised in red sauce and the classic white mushroom sauce, I am more courageous to repeat them this year.

What’s on your table?

Melanie

Two-tier financing in Medieval Islam

The development of banking or any of its forms did not begin with state sponsorship, as Graeber argued. This can be clearly discerned in the Middle East example. There did not seem to be a smooth transition from the coinage-military-slavery systems we have been discussing in the past (see the four-part series on India, three-part series on China and the Far West). Rather, we have two-tier systems that can operate independently from each other.

Context

The timeline of our concern is at least a hundred years after the Prophet died in AD 632. The medieval Islamic period we refer to is the Abbasid Caliphate (AD 750-1258). Their rule was a revolutionary usurpation from the Umayyads (AD 661-750) who were the successful victors following the leadership vacuum after the death of the Prophet.

Prior to their ascension to power, the Umayyads were significant, says Taleb El-Hibri

They were the first to establish the hereditary monarchial institution of the ‘caliphate’ patterned after the early Persian Sassanian dynasty (AD 224 - 651)

Their caliphate rule is a confederacy of Arab tribes that discouraged Islam conversion because the taxation on non-Muslims or jizyah was one of the backbone of their funding (the other is the land tax)

These two developments were central to the motivations of the Abbasids to usurp power from the Umayyads.

There was a question of legitimacy from different Muslim heirs. They were all vying for the right to rule and interpret what a caliphate should be. In his work, El-Hibri explained that the term, meaning ‘deputy’ or ‘successor’ in Arabic, remained ambiguous. The Arabic term can mean ‘the deputy of God’ or ‘the representative of God on earth’. The interpretation of which is the source of the succession conflict in the region.

The Arab-based power of the Umayyad was counter to the vision of the Abbasids, who were the Hashimite branch of the Prophet’s uncle al-Abbas.

They wanted a pan-Islamic kingdom beyond the restricted Arab identity.

They also wanted a fusion of the political office with religion which would be established as the dawla.

It was under the Abbasid that the institutions of government, law, and culture flourished under what El-Hibri calls, a new order. They would rule the golden age of Islamic life with Baghbad as its centre.

Tier one: military funding complex

The bureaucracy of the Abbasid was inherited from the preceding rulers: the Umayyads and before them the Rashidum caliphs (AD632 - 661). They, in turn, borrowed from the Sassanid and Byzantium taxation systems given that Abd al-Aziz Duri says that the Arabs were poor in finance. In the early days of designing fiscal bureaucracy, the best strategy is to copy! These would form the tanẓimāt or the systematisations that would become the foundation of the Islamic legal system on financial matters.

There are two ways that the kingdom funded its coffers:

A poll tax called the jizyah extracts from the protected non-Muslims, ahl-al-dhimmah, who were part of the conquered people in their lands. This is waived once they convert to Islam.

A land tax called the kharāj is a tax paid by a farmer to the landowner depending on a person’s wealth or crop harvest

Alternatively, an ‘ushr’ is a tithe of one-tenth (or variations of thereof) based on the produce harvested

This taxation system cleaved the population into two. According to al-Aziz Duri, those who were Muslim tended to be warriors and those who were not remained in agriculture. The funds from the latter, including other forms of extraction from land, goods, and people, fueled the former.

The military is essential to the kingdom. According to a Persian Abbasid translator and scholar, Ibn al-Muqaffa’s Risala fi’l-Sahaba, a statecraft document, the government must pay attention to its military affairs:

it must ensure that the soldiers were paid on time

it must secure the value of the wages against inflation

This was a central preoccupation of the government—taxation and military affairs. For good reason.

However, this system of funding would become unsustainable as military officers were paid in land grants instead of cash, iqta’ or daman.1 Land grants were tax-exempt. Thus, the tax source diminished and gradually defunded the army.2 This meant that the army eventually relied on military slaves, such as the Mamluks, as conscripts.

This government tier system is a closed loop of extractive practices from the land and its people to fund its army.

Tier two: the trust and credit system

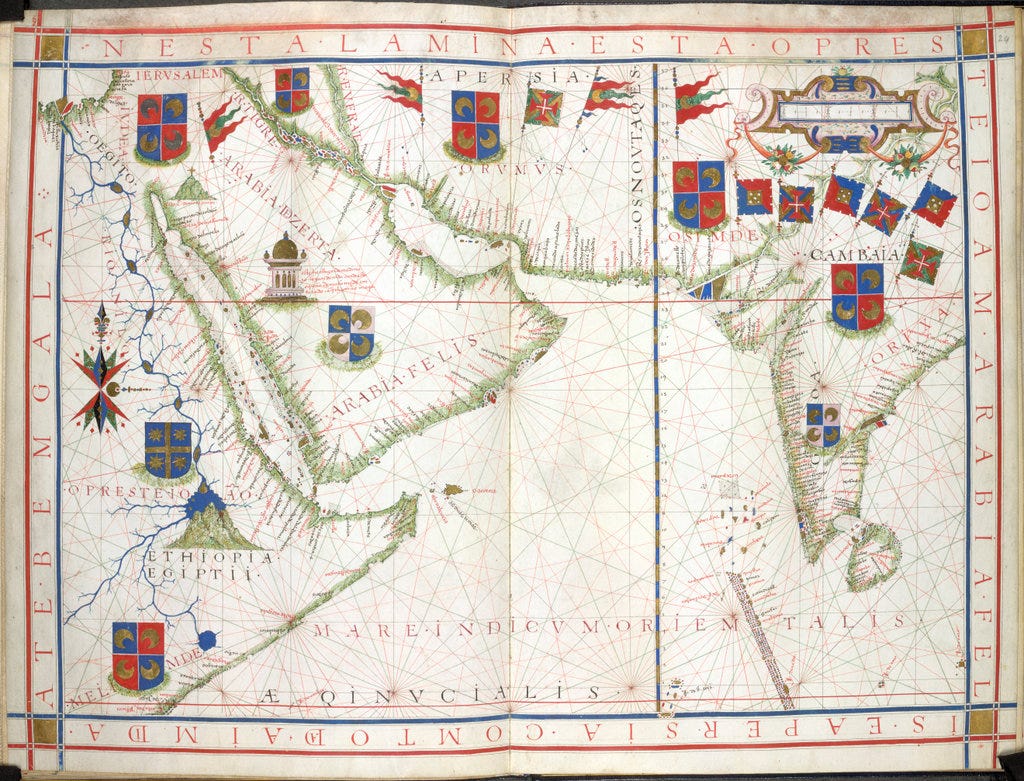

Meanwhile, the merchants and the common man possessed multiple options outside of government control. These are closed and simultaneously open networks of trust and reputation recorded on letters of credit suftaja. This is a promissory note system that is as good as cash without government regulation or enforcement. Any conflict was mediated by merchant guilds and civic associations. Recourse to the legal courts was only voluntary.

These credit instruments allowed for wealth accumulation and lending but also easy money transfer within the trading network. More importantly, with a handshake, these credit partnership investments funded both sea trade in the Indian Ocean and Islamic conversion. It is because these same traders were also legal scholars and part of the Sufi brotherhoods. Inadvertently, these enterprises were the first informal banking infrastructures.

Compared to those tied to the land, the traders appeared to be freer in profiting from their own labour with minimal government interference.

Once freed from its ancient scourges of debt and slavery, the local bazaar had become, for most, not a place of moral danger, but the very opposite: the highest expression of the human freedom and communal solidarity, and thus to be protected assiduously from state intrusion.

p. 278-279

The controls on profit and usury were a combination of religious doctrine, social shame, but also prestige.

The veneration of the merchant was matched by what can only be called the world’s first popular free-market ideology.

p. 278

Why this system is not used by the government to fund their armies (rather than spend onerous time trying to control this market) is indeed, confounding. This goes to show how separate the machinations of the government with the everyday life of their subjects.

Post script: On coinage and meaning

In the concluding remarks in the text, Graeber added a curious entry into the concept of coinage. He opines that there is a convergence between Western economic thinkers with their Mideast counterparts on the division of labour. The points are the following:

Not all men are equal. People are distinct and therefore have different needs. In the Islamic notion of inequality, there is a specific responsibility and accountability between people from different hierarchies. You can assertively negotiate with the rich so that you can be charitable to the poor.

The market is supposed to match needs between two figures of unequal worth

The best medium to match two unequal entities is something that ‘lack(s) any particular feature other than value’

Coinage, as Al-Ghazali (AD 1058 - 1111), a Persian polymath and philosopher defines is one such example of a material that lacks any ‘particular feature.’ It is only a medium of meaning. The exchanging parties constitute the meaning, not the object itself. Interestingly, Graeber points out that this idea renders profit ‘illegitimate’ for there is no meaning in of itself. The value, says Ghazali, is in the movement of gold and silver rather than a coin’s inherent properties.

It is a good reminder of what money is supposed to be.

Round-Up

The Islamic capitalist model differs from what we have seen in the Buddhist monasteries in India and China. Unlike the monasteries, the merchants are themselves the walking banks. They are not just traders but also religious figures who convert souls in the process.

This is possible because the Abbasid caliphate inadvertently built a two-tier financial economy that created two spheres of transactions.

The political sphere relies on its military to maintain its power. Therefore, it copied what previous empires had done—tax the agricultural sector and non-Muslims under their control (a true submission under Muslim rule) to sustain its soldiers’ wages

The mercantile sphere operated under trust and social reputation which created the earliest recorded credit instruments that were acceptable outside of its borders

Though Graeber did not explicitly talk about usury and profit, clearly there are guardrails about the abuse of extractive practices (including the government) both on moral and social grounds. This is because social differences in Islamic law, especially those with wealth and those without, prescribe the appropriate interactions. Money and markets are the perfect vehicles to measure two unequal entities. The measures of their worth are found in the relations of exchange. Not in money, or coinage, itself. This approach meant that profit or earning money for money’s sake is ultimately a meaningless enterprise.

Re-read the previous post:

Chapter 10 (Part 4): Early Capitalism in Chinese Buddhist Monasteries

The Mahayana Buddhism strand in China (AD 404 - 825) ushered the development of unbridled monastic capitalism. Its success was also the same reason for its downfall.

This system is similar to how the armies and loyalties in the early period in Axial Age China were funded.

So much so that when the Abbasid tried to wage war against the Byzantine, they had to beg for money! They lost that war. (I’m trying to find that exact quote in al Aziz’s work about begging for cash or reporting that the court did not have enough funds to wage war. Alas, I couldn’t at the time of posting.)