Chapter 10 (Part 4): Early Capitalism in Chinese Buddhist Monasteries

The Mahayana Buddhism strand in China (AD 404 - 825) ushered the development of unbridled monastic capitalism. Its success was also the same reason for its downfall.

If you are new here, we are reading David Graeber’s Debt: The First 5,000 Years. Catch up and join us on Thursdays in 2024. My first slow read here on Substack in 2023 was David Graeber’s The Dawn of Everything. These two books showcase his thesis on the development of humanity by looking at how debt evolved and how people organised themselves and their world. Unique among his peers, Graeber still asks the big questions in anthropology.

Dear Reader,

We definitely will not finish the book by the calendar year and that’s okay. It is better to tease out the key sources and arguments one bite at a time.

By January or February, we will begin with a new series I am cooking up that has to do with the history of anthropology (multiple books) or Piketty’s Capital. Let me know if you have thoughts on this. I am apprehensive about the latter because I am not an economist by training. I do am excited with creating a new syllabi that is urgently needed with the rapid defunding of the social sciences and humanities among other subtle assaults lately.

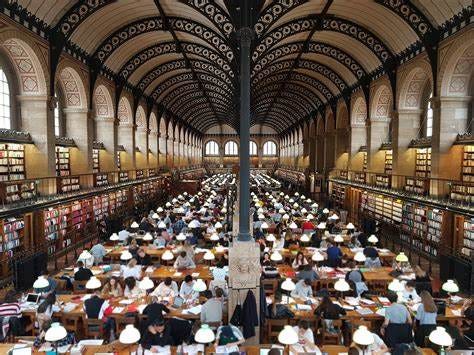

I take comfort that libraries such as Bibliothèque Sainte-Geneviève remains open for quiet reading and contemplation in Paris. I spent wonderful hours discovering and reading hard to find anthropology gems from very helpful staff in my last trip. If only I can spend all day everyday here. These students are lucky.

Melanie

Charity and commerce in China

Graeber puts forward a bold proposition that capitalism in China began with the Buddhist monastic practice. He means using money to produce more money (the concept of profit - MCM - money-commodity-money) and calls this monastic capitalism1.

We have a better analysis when it comes to what is recognised by scholars as religious capitalism happening in medieval period China. There were more surviving records of monastic transactions, biographies, and business transactions including stele monuments and the documents found in the Dunhuang caves. Currently, a large joint project has been conducted by the British Library to digitise the research collection found in Cave 17.

Jacques Gernet’s Buddhism in Chinese Society is an important work that referred to these materials. Though written in the 1950s, it provides a foundation during that period. Another source that Graeber used is Peng Xinwei’s Monetary History of China as well as Randall Collins’ Weberian Sociological Theory.

For Gernet, the relevant period begins when the Indian treatises were translated into Chinese. These were called the four great Vinaya that prescribed how Chinese monks should live. This was between AD 404 - 424 under the Eastern Jin dynasty. The construction of elaborate monasteries and the accounting records peaked during the Tang dynasty, AD 618 - 907.

Sociologist Randall Collins argues that Buddhism had the greatest influence than Confucianism and Daoism (59) during this period. This was the time when the population fled to the south with the invasion and threats from the north. Thus, the early communities flourished in the southern region. He describes a transformation of the Buddhist practice from a magico-ritual practice to a return to Buddhist meditation, monasticism, and philosophy. This followed from the translation of the scripture right about that period.

The impact of Buddhism throughout society is as follows

It enjoyed dynastic support, especially during the years 680-701 and 705-712; this support would waver and shift in various periods, especially as it accumulated enormous wealth

It was the religion of the common people in contrast to Confucianism and Daoism (which would later also create a populist model)

Buddhist monasteries were a steady economic unit that possessed land, slaves/serfs, gold/copper and had mercantile and entrepreneurial businesses

To answer our question, “Were monasteries the first banks in China?” The answer is a resounding yes.

The book by Gernet is a fascinating read about the socio-politico-legal organisation that is the monastery and the monks that inhabit them. Not just that, Graeber calls it the ‘first genuine forms of financial capital…constantly seeking opportunities for profitable investment.’ It rivalled what was happening in late medieval Europe.

Why is profit logical in Buddhism?

Graeber (260-267) provides us with an explanation using the logic of exchange to the idea of redemptive eternity put forward by Buddhisim. He says that the theology of debt, though highly imperfect, has the possibility of becoming genuine—that is, the abandonment of material needs and wants to achieve liberation.

However, this did not happen

Liberation is only completed when the others are. This Mahayana interpretation means that one’s redemption is on a standstill in perpetuity. However, ‘one purchases felicity, and sells one’s sins, just as in commercial operations.’ It follows that one’s gifts to the monastery can ensure that a little bit of redemption is done even after one’s death.

The acknowledgement that some debts can never be paid e.g. the debt to a parent, therefore repayment can only happen through sacrifice; the total surrender of one’s life or material goods to the community allows one to draw redemption from the community pool

It makes sense that monasteries became the recipients of the largesse of families and individuals. Not only that, monasteries triggered a whole host of activities that supported craftsmen, technicians, artists, and more. Their location is accompanied with the flourshing of business and trade. They run hotels, carriage parks, mills, shops, and farms.

Accumulating assets

Economic self-immolation, says Graeber, is the ultimate sacrifice that ensures that the coffers remain overflowing. These treasures classified as the Inexhaustible Treasures, a permanent or principal endowment, are then used to grant loans or are invested in other activities.

…an object of eternal value, an investment that can bear fruit for all eternity.

p.262

Coins

While cash seems to be the assumption, it is only a small part of their holdings. However, its accumulation seems to be so significant that political decrees attempted to limit them

Yuan-ho (AD 817) prohibited both Buddhist and Taoist monasteries to hold more than 5,000 strings of cash; large Buddhist monasteries often rolled out 100,000 strings of cash from their pawnshop business

In AD 713, confiscation of the Hua-Tu and Fu-Hsien coffers were done because these monasteries would receive ‘cartloads of cash’ from great Buddhist families at the beginning of every year

Although many of the monastery cache were in metals—gold and copper, these come in the form of ritual objects and ornaments. Nevertheless, the amount of metals decreased from circulation. Hence, periodic repressions occurred against Buddhist temples such as those made by the Chou emperor Wu (AD 574 and 577) and Wu-Tsung (AD 842-845). It was one way for the imperial office to retrieve copper to mint into coins. It was also prohibited to cast Buddhist statues from these melted coins and it is punished as a counterfeiting crime.

Charging interest and pawnshops

A new form of loan was introduced in China and this was the use of pledges chih against loans from Buddhist monasteries. It was usually in cash form. However, some pledges were personal objects called tien that possessed moral meanings from the debtor. The objects themselves were usually assessed below the market prices. The monasteries then granted loans against these pledges creating an early form of pawnshop ch’ang-sheng k’u. Some loans may be for an undetermined period.

The difference from the modern era was that these loans were usually granted to people who already had wealth or members of the elite or officials.

Agricultural banks

For the peasantry, the prognosis is bad. These monasteries were the early agricultural banks whose main purpose was the loan of seeds and planting provisions for the next agricultural cycle. The rates were short (seven to eight months) and quite high, reaching as much as fifty percent. Clearly, these were usurious even if the seed loans were small.

Monasteries, such as the one in Shansi loaned out millet to farmers because they owned large granaries. The Ching-t’u monastery near Denhuang caves owned a granary that can contain up to four hundred hectoliters of cereals. Some, like the Sha-chou region monasteries, can own up to five thousand hectoliters of cereals. The poor borrowers had to return twice the amount by harvest time. This was the standard rate. If not, the seizure of his property shall be done, whether or not he submitted a pledge. His heirs shall pay the monastery back in case of death.

The rates that Ching-t’u were charging meant that they earned about a third of their loans (from a total of 136 shih of wheat and millet) to usury. These were non-productive profit that made and kept the peasantry poor.

These usurious rates and accumulation of wealth made the monasteries periodic targets of the government, its religious competitors, and the population. They were subjected to a series of government control that began in the 620s that required a government ordination certification and the selling of monastic ranks. A great persecution of the Buddhist monks in AD 845 led to the confiscation of wealth in all monasteries. The numbers won’t recover until 1221.

Collins hypothesised that though Buddhism in China spurred a thriving secular economy, its success scared its Confucian and Daoist counterparts and led to its purge. He says that there is strong evidence to argue that its downfall led to the economic stagnation in China.

Round-Up

Buddhist monasteries were also the first banks in China. Records show that multiple financial instruments were developed including the system that we recognise from pawnshops today.

The findings here share a commonality with the Indian example: the Buddhist influence

spurred financial development and trade that gave rise to religious capitalism (money-commodity-money)

profit through charging interest, most times usurious rates, are necessary to ensure the viability of religious structures and the maintenance of principal endowments

the religious tenet of commonality and community is intimately tied with the birth of capitalism

It has surprised me how much Buddhist practices contradicted its teaching just like any other large religious organisation. The theology of debt can be understood as follows:

All debts must be paid; exchange transactions can be quantified in market terms

In cases where debt cannot be paid e.g. karmic debt or parental debt, these can only be acknowledged through sacrifice or the surrender of all material gains and benefits (its ultimate expression)

It is the latter sacrifice that creates the paradox in Buddhism. This is the fate of the spiritual as we cannot escape the material.

Re-read the previous post:

Chapter 10 (Part 3): Monasteries and Temples as the First Indian Banking System

The early medieval monasteries and temples in India were ironically the purveyors of early interest bearing loans and potentially usury practices.

Randall Collins calls his religious capitalism, see his work on Weberian Sociological Theory