Chapter 10 (Part 3): Monasteries and Temples as the First Indian Banking System

The early medieval monasteries and temples in India were ironically the purveyors of early interest bearing loans and potentially usury practices.

If you are new here, we are reading David Graeber’s Debt: The First 5,000 Years. Catch up and join us on Thursdays in 2024. My first slow read here on Substack in 2023 was David Graeber’s The Dawn of Everything. These two books showcase his thesis on the development of humanity by looking at how debt evolved and how people organised themselves and their world. Unique among his peers, Graeber still asks the big questions in anthropology.

Dear Reader,

It seems there’s a spy renaissance on television lately with one series after another launching: The Day of the Jackal (Eddie Redmayne), The Agency (Michael Fassbender), The Diplomat (season 2), The Lioness (season 2), Black Doves (showing tomorrow on Netflix). London is getting more beating after Slow Horses.

In celebration, I watched the original 1973 Zinnemann film, The Day of the Jackal with Edward Fox. Since I visited the Musée de la Liberation in Paris (excellent, must see and do! Visit a real air raid shelter 100 steps beneath the building!), I understood why the assassination of General De Gaulle was a key piece in the plot. There is an important postscript at the end of the museum exhibition about the De Gaulle and the loss of Algeria.

This movie remains gripping and thrilling! It holds up quite well. Everything analogue (and old cars) seemed so pretty and efficient. You don’t need movie effects to show the beauty of every country the Jackal visits. All you need are smart people doing their job. Plus, everyone seems to be wearing a suit! What a time.

Melanie

Charity and commerce

To answer our question, “Were monasteries the first banks in India?” I argued that three incidents had to happen first. In our previous post, I outlined a critical timeline:

Ashoka’s renunciation of violence led to his total capitulation to Buddhist teachings. We know this because he was the only one in his Mauryan (322 -185 BC) lineage who inscribed it permanently in stone. Think of it as an anti-Hammurabi Code that advocated for ways to build peaceful and ethical infrastructures. (I wonder why his code wasn’t more popular).

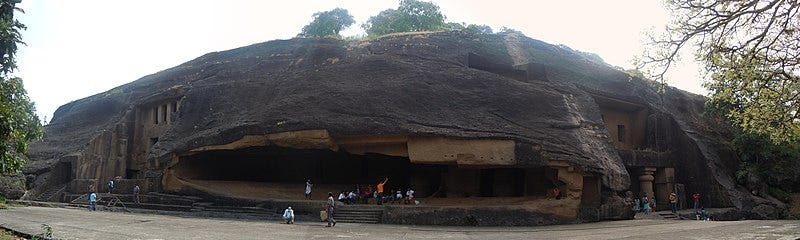

His official acknowledgement led to the institutionalisation of the Buddhist practice. The construction of monasteries and ascetics retreating to their caves expanded across the kingdom.

The increase in trading traffic during and following the Mauryan period brought Indian goods and ideas elsewhere, including the spread of Buddhism as far as China and Southeast Asia.

Of course, the Indian philologists during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries must be acknowledged for translating texts that promoted access to the life and times in Indian prehistory.

A lot of what we know about this period comes from the translation of several texts:

the state, economic and political philosophy text, the Arthaśāstras

the translation of the Smṛtiśāstras, which provide moral and ethical guidelines such as those found in the Manusmṛti and the Yājñavalkyasmṛti, the latter has been the source of our understanding of the Buddhist relationship with money and debt

Both Graeber and R.S. Sharma have extensively written about the economic history of the medieval period in India using these same materials. Sharma himself wrote a critical analysis of Indian historiography linked to the nationalist project. He also focused on neglected topics such as the analysis of Indian coinage. Nonetheless, the information discussed here is thanks to the translated texts from Buddhism and Hindu sources directly related to money and interest.

Debt and religion

It was not only the Christian church in Western Europe that possessed wealth. The phenomenon also extended to Buddhist monasteries through ‘perpetual endowments’ or akṣaya-nīvī.

Gregory Schopen, in his article on monastic loans and contracts, defines the first Sanskrit word as ‘permanent’ referring to a donation or gift given by a donor to a community of monks. The condition of the donation is that the principal amount is not to be touched or must remain permanently intact in perpetuity. In order to sustain the monks’ needs, this principal amount must be loaned out and the interest or vṛddhi earned is what they can use to spend.

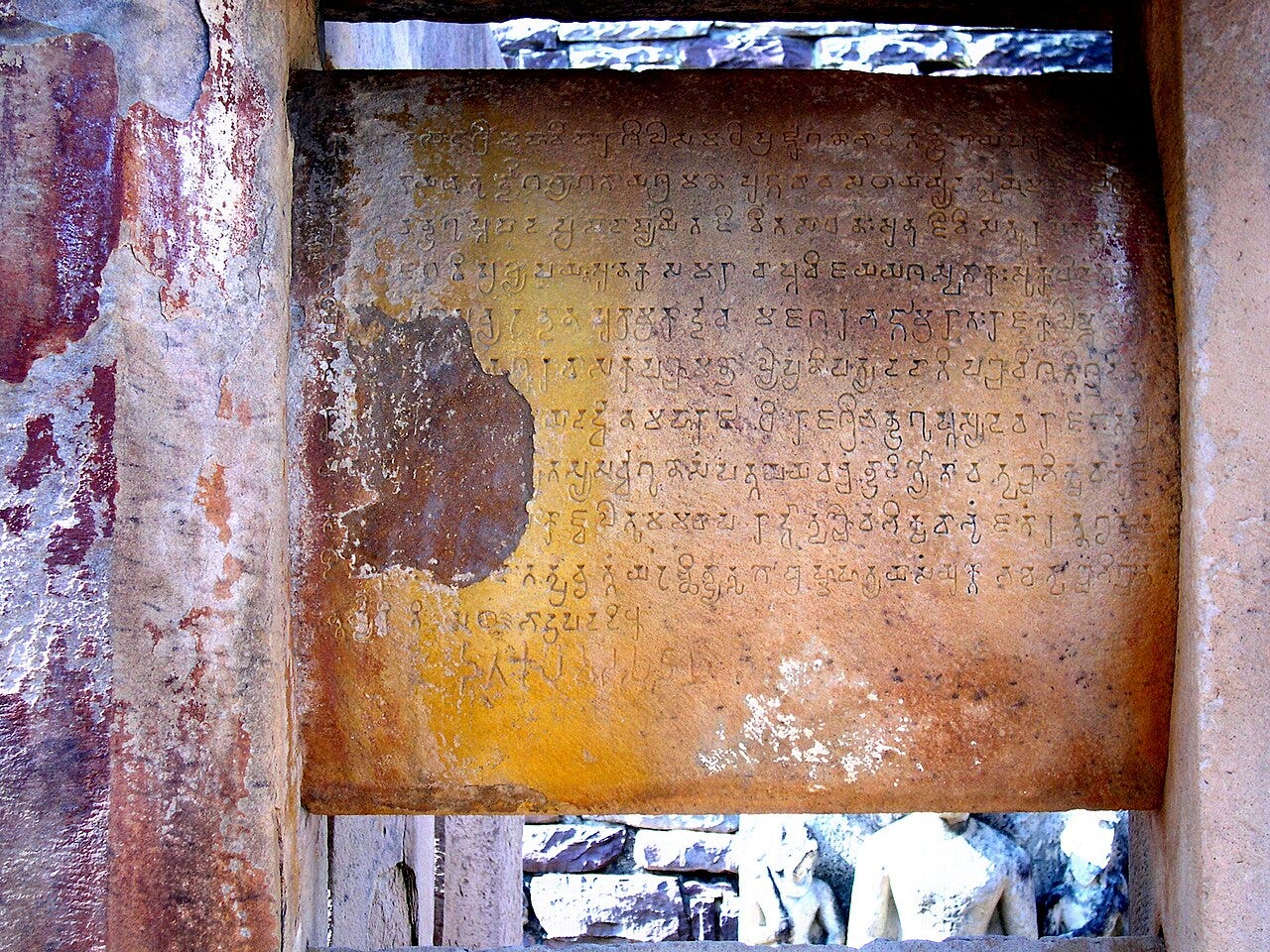

The term has been found in the temple inscriptions from Alluru as early as the first century AD.

The term has also been found in the Kanheri caves, west of Mumbai, with inscriptions dating to the Satavahana period from the second to the third century AD.

A typical donation includes three dīnāras with the interest used to light three lamps daily for the Buddha. This was found among the inscriptions at Sanchi in Madhya Pradesh.

Inadvertently, to achieve enlightenment, the monks and practitioners must become wealth managers and account for the material goods that flow into their coffers.

Charging interest

Wealth accumulation has its paradox.

…for the sake of the community a perpetuity for building purposes is to be lent on interest.

Buddha, from Schopen, p. 535

When monks are under training they are usually instructed that lending interest is not acceptable. A Buddhist vinaya states that a brahmana and even a kshatriya should not lend on interest. However, the exception is made when the purpose is to benefit the community. This includes activities beyond building and covers religious purposes.

How much should the interest be? According to Schopen (p. 537), the interest should not exceed twice the value of the loan as a general rule in the dharmaśāstra1. Schoper translates this as ‘doubling’ from the term dvaiguṇya. No more, no less, regardless of any length of time accrued. This pledge as they call it is written up as a contract, a likhita or lekhya, between the creditor individual and the monastic institution (the Elder of the Community and the monastery provost) with a legal seal and a witness. These forms are known to us as a letter of credit.

The amount of pledges to a given community presents a conundrum. The monastery now holds infinite value and requires a ‘devout lay brother’ to help them hide the treasure. Pledges come in two forms. A gopya are pledges for custody or those to be kept. A bhoyga are usufructuary pledges or those items that the monastery can use to profit from. Pledges can include cloth, copper pans, female slaves, fields, animals, and such. This care responsibility requires a devout helper who may be tasked with other financial activities. This separates the monks (spiritual) from directly being involved with the material and financial transactions.

Donors gain merit, especially after their deaths, as long as their donations continue to ensure that the monastery or the vihāras remain habitable.

From interest to usury

Hinduism gradually replaced Buddhism as the dominant religion between the fourth and sixth centuries. This was noticeable with the monthly interest rates charged by Hindu temples according to the different caste members of society.

two per cent for a Brahmin

three per cent for a Kshatriya (warrior)

four per cent for a Vaisya (merchant)

five per cent for a Sudra (labourers)

Debt was now inevitably linked to caste identity. Those in the lowest levels were subject to harsher debt rates that could last for generations (according to written tradition, up to three before any full pardon). By 1000 AD, any restrictions on interest rates have been removed. The rates seem to approach usurious terms as perishable commodities loaned to community members were double the term or tripled if payment was late.2 The term vārdhuṣa refers to usury. Those who cannot pay may be compelled to offer their labour to repay the principal and compounding interest.

It appears that Hindu temples invested money in merchant guilds to accrue interest. However, their principal market was the ordinary peasants with whom they lent land and grain and charged usurious rates.

The concept of sin or punishment did not appear as a factor in removing this practice. Rather, unpaid debts were an egregious sin in itself. One cannot enter the Buddhist order if you had unpaid debts. In the Hindu religion, cyclical punishment is an escalating interest rate peaking up to ‘1,000 million’ and then returning as a slave, a horse or an ox. The coming of Islam would balance this Hindu practice.

Next week, we shall examine the medieval China experience.

Round-Up

Christianity was not the only religion that accumulated wealth. Indian monasteries and temples were also the first banks that stored and lent goods, land, and animals to guilds and ordinary villagers. The establishment of the early Buddhist monasteries and Hindu temples ushered in the early village banking system in India.

The critical difference is the rates and acceptability of charging interest. In the Buddhist instruction, double the loan rates were acceptable means of interest. The terms of interest escalated during the Hindu transition when moral or ethical controls were removed socially and legally. Higher rates were imposed on ordinary folks that subjected them to onerous and generational debt peonage status.

Churches, temples and monasteries are in a paradox. To maintain their spiritual goals, religious leaders had to deal with the financial complexity of becoming material benefactors of wealth to sustain themselves. The moral and ethical implications of interest and usury only seem to rest on the non-payment of debts rather than its imposition on the people.

Re-read the previous post

Chapter 10 (Part 2): Ashoka's Age (265-238 BC) and Buddhist Expansion (450 BC- AD 1200)

The foundation of the first banks in India is through Ashoka's conversion. Charity and commerce together would become the medieval age.

These law codes were written by Brahmin scholars between 200 BC to 400 AD. These were directed towards the Brahmins who were bound to embody and enact the learnings as a member of the elite.

More terms of credit can be found in Sharma’s Usury in Medieval India (A.D. 400 - 1200)