Conclusion (Part 1): Why Marxism and Islamic Economics Fail as Alternatives to Capitalism

Even Graeber succumbs to the romanticism of communism and Islamic Economics

If you are new here, we are reading David Graeber’s Debt: The First 5,000 Years. Catch up and join us on Thursdays in 2025. My first slow read here on Substack in 2023 was David Graeber’s The Dawn of Everything. These two books showcase his thesis on the development of humanity by looking at how people organise themselves and their world around human values and choices. Unique among his peers, Graeber still asks the big questions in anthropology.

The End?

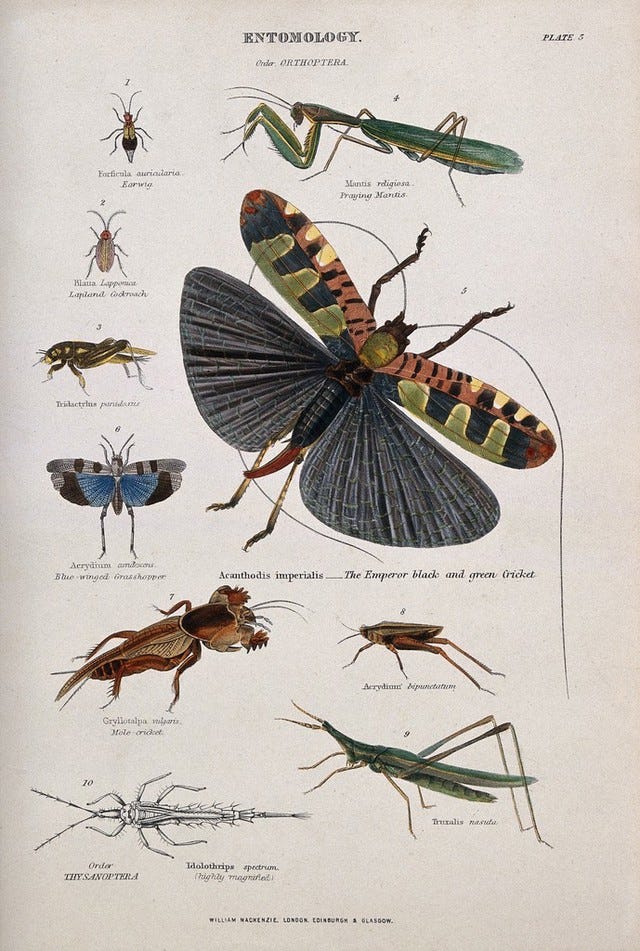

It is an anticlimactic end from David Graeber. Even I was not expecting it. I was hoping for fireworks, the big reveal, but all I got were crickets. I read until the end. After all the chapters, all I got was a whimper.

But I do understand, after all the dense chapters, even he probably got lost in the branches. Never to recover. Not to say I don’t love the guy, but somewhere in there are nuggets waiting to be used.

He does not promise any answers. That was expected (but also wishful thinking on our part.) His point is to open the reader’s minds to the possibility of other futures outside of capitalism.

Let’s do this!

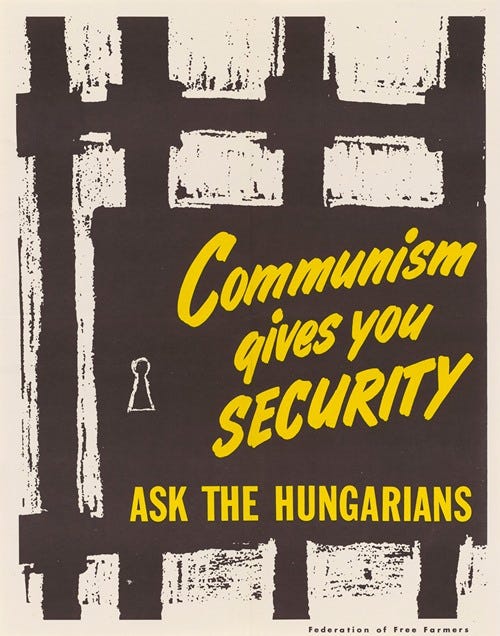

A failed ideological experiment: Socialism/Marxism

We already did experiment on one alternative, famously in the heyday of the 1970s, as welfare capitalism was on the wane in the U.S. and Great Britain— communism. In post-World War II, Europe was carved out and awarded to the Soviet Union as part of their spoils of victory. We saw the loss of Berlin and Eastern Europe as they went under the ‘Iron Curtain.’ A second world emerged in the 1950s-1980s when American capitalism could not trade with countries that experimented with a closed, supposedly self-sufficient economies. Rather, socialist countries traded with each other. You could study abroad and vacation in other communist countries if permission were granted.

China’s turn to militant socialism was to thwart the weak rule of the Qing Empire (1636-1911) and to solve the poverty, food, and mainland foreign incursions. In my literature review for my dissertation, the investigation by husband and wife anthropologist team, Sulamith Potter and Jack Potter, in rural China showed that women were recognised and paid for their rural labour.1 They got paid for it. It is one important win during the collectivisation period. However, other negative outcomes, such as food shortage and eventual hunger and starvation, when 15-30 million people died as a result of the prohibition on tending household gardens and reliance on collectivised farms and kitchens (and misreporting). In other words, the elimination of household-level self-sufficiency (land and private property) was disastrous. Everything had to be in service of the state. This is one example of how humans attempted to implement ideas like the prohibition of private property on a massive scale (using the end of the gun). The result did not work at all.

I dislike it when Graeber and other scholars of my generation conveniently forget and sidestep how insidious communism implemented in authoritarian regimes is. (Or worse, it gets romanticised by the generation born in the post-Cold War era.) Both capitalism and communism are violent and oppressive systems when human governance is involved. Graeber laments, though, that human imagination faltered after the Soviet Union fell in 1989 and succumbed to the faults of capitalism en masse. In this, I agree.

Now, this is true. Levi’s, Coca-Cola and Rock’ N’ Roll trounce communism. At the other end, Graeber beleaboured on capitalism’s inbuilt tendency to catastrophise our future. You choose.

Graeber’s misplaced confidence in Islam

In his move away from a Western, militarised, Christian variant of capitalism, Graeber discounts the potential of transformation in the West and turns to Islam. He inquires about Iraq and the Islamic Middle East for new ideas because it was here in 3000 BC and AD 800 that interest/profit had been developed and rejected. Unfortunately, Islamic economics, he says, remains superficial, with interest-free banking not fully becoming transformational because these institutions operate like profit-making banks, as well. Timur Kuran, an Islamic Economics Professor, further explains why. He traces the first banks, similar to the institutions that we have now, from Western models in the 1920s and 1970s. Kuran contradicts much of Graeber’s romanticisation of Islamic economics, which is pretty mainstream. Some common widespread ideas include:

the prohibition of interest as part of the pan-national Islamic identity

an in-built mechanism for the redistribution of wealth to the poor

These ideas, Kuran argues, are rarely questioned. For good reason, one has to be an economist, an Islamic historian, and fluent in contemporary Islamic culture at the same time. Unlike other ‘indigenous’ researchers working in this field, Kuran identifies key analytical problems: get ready…

cultural relativism

multiculturalism

These concepts, inherent in the liberal ideology dominant today and the bedrock of the discipline in anthropology, were used as a way to remove Western blinders end up as the blinders themselves when it comes to Islamic Economics.

There is a reason why Islam, Islamic economics, like socialism, has not eradicated poverty or become more dominant than capitalism in the fifty-six Muslim majority countries. In Kuran’s work, Islam and Mammon, he argues that people privately reject interest-free banking and choose conventional banks instead. Moreover, the courts do not totally adhere to the Sharia Law banning interest outright under pressure from the business community.

In the first Arab Human Development Report in 2002 from the UNDP (United Nationals Development Programme), Kuran identifies three things that challenge the development in the region: the freedom deficit in political participation, the women’s empowerment deficit, and the education deficit. These same problems now sits on top of the challenges of the environment, social trust in the government, and continued gender discrimination in 2022. It seems a pipe dream when Graeber suggests feminism and Islamic feminism as potential sources of new ideas. But the fight continues among Iranian women for political participation despite an Islamic interpretation of limited participation as in Afghanistan. Perhaps, I should not discount it yet.

However, time is running out.

Let’s clarify and revisit some of the big questions that Graeber presented but never answered:

Can we ever escape debt in human relations? If not…

Is there a morally acceptable form of debt relations?

What did atheist Graeber miss by not looking into the Judeo-Christian concept of redemption?

It’s not the end of the journey, yet. This has been personally fulfilling in improving my writing, reversion to Roman Christianity, and finding what excites me about anthropology.

Round-Up

I chose two points in Graeber’s conclusion that stood out to me as erroneous and needed a spotlight. Though he did not explicitly suggest a clear pathway and clarification, I hope to discuss this in successive posts.

One is his glossing over the failures of socialism/Marxism as one big human thought and conceptual experiment that we have already done. The results were not any better or less violent, even if it had lofty ideas such as collective farms and communal dining and working. I highlighted one significant consequence: the persistent food hunger and eventually famine as a result that killed an estimated 15 to 30 million Chinese. This was the Great Leap Forward.

The second is Graeber’s romantic view of Islamic economics rooted in Medieval Islam’s precepts:

prohibition of interest/usury

redistribution of wealth to the poor

Though very attractive, Islam historian and economist, Timur Kuran offers a contrary view that deserves closer reading. He links it to our Western blinders of cultural relativism and multiculturalism that prevents us (including scholars like Graeber) from seeing ‘Islamic economics’ as a modern invented tradition. There’s less of the medieval model in contemporary Islam economics than its primary purpose as a universalising pan-Islamic identity.

More to come.

Hi Readers,

I am excited in expanding the conclusion and sharing my own transformative journey reading Graeber’s work. Looking forward to my upcoming journey! Enjoy the rest of your summer.

Onward, Melanie

My favourites this week:

and a mind-blowing book if you are travelling or have been to Australia

Recommended Sources:

Dikkötter, Frank. 2010. Mao’s Great Famine: The History of China’s Most Devastating Catastrophe, 1958-1962. London: Bloomsbury Press.

Kuran, Timur. 2004 [2006]. Islam and Mammon: The Economic Predicaments of Islamism. Princeton: Princeton University Press

Potter, Sulamith Heins and Jack M. Potter. 1990. China’s Peasants: The Anthropology of a Revolution. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

UNDP (United Nations Development Programme). 2022. Arab Human Development Report 2022: Expanding Opportunities for an Inclusive and Resilient Recovery in the Post-Covid Era. New York.

UNDP (United Nations Development Programme). 2002. Arab Human Development Report: Creating Opportunities for Future Generations. New York.

Wemheuer, Felix and Frank Dikkötter. 2011. Review: Sites of Horror: Mao’s Great Famine [with Response]. The China Journal 66 (July 2011): 155-164.

Find your way around: the book outline

Debt: The First 5,000 Years

Our 2024 read is another highly cited but intimidating David Graeber book! He argues that debt should be the central point in the study of economy and money. He also thinks about creating a humane money system.

Re-read the previous post:

Addendum: Chapter 12 (Part 2): The New Class Struggle: Microloans and Debt Payments

Microloans rebranded charity into entrepreneurship while NGOs enforce debt payment as a form of self-discipline.

I’ve been searching for the exact ethnography of rural village life for hours! So I have to publish this without the actual reference. If anyone wants to know, reach out to me directly. I am also in earnest trying to find an old blog entry that I have written that had this citation! But alas, at the moment, I better get on with this! Edit: I found it! China’s Peasants by Sulamith and Jack Potter.