Addendum: Chapter 12 (Part 2): The New Class Struggle: Microloans and Debt Payments

Microloans rebranded charity into entrepreneurship while NGOs enforce debt payment as a form of self-discipline.

If you are new here, we are reading David Graeber’s Debt: The First 5,000 Years. Catch up and join us on Thursdays in 2025. My first slow read here on Substack in 2023 was David Graeber’s The Dawn of Everything. These two books showcase his thesis on the development of humanity by looking at how people organise themselves and their world around human values and choices. Unique among his peers, Graeber still asks the big questions in anthropology.

Debt as Class Struggle

Debt in North America has both spiritual and material dimensions. Last week, we looked at one work that aligns with the neoliberal economy that is identified as the American Evangelical Right. This week, we’ve got several from the ‘American Left’ and the prognosis seems to be the same—debt has become an equal leveller of status and class.

…neoliberalism has thrown open a new dimension of struggle between capital and the working class within the domain of credit.

p. 7, Promissory Notes: From Crisis to Commons from the Midnight Notes Collective and Friends

There is a paradox to debt that tells us to empower ourselves by participating in the credit economy. At the same time, we might fall in into a credit trap without any recourse. It’s a thin line. Anyone who has acquired too much needs to be shamed or absolved, so goes the religious analogy among the (atheist) Left. Margaret Atwood’s 2008 Massey Lecture on Debt, noted that obtaining debt has acquired the siniciture of sin—one that has to be purged and removed, judging by how many podcasters and debt saviours offer sermons from their pulpit to tighten their belts, “rice and beans.” With the way credit has outstripped income, it is unsurprising that to get rid of hundreds of thousands of dollars of debt, requires suffering on a cross and a long road to Golgotha (only to be crucified in the end).

Debt and power, sin and redemption, become almost indistinguishable.

Freedom is slavery. Slavery is freedom.

p. 380, Debt, David Graeber

Graeber argues that this hits the poor the most because underlying such purposes are social relations themselves, especially in the Black, Latino and American immigrant communities. According to him, expenses in human relations cannot be postponed compared to consumer items, such as a debutant party or for a grandparent. Hence, it is common to label and attribute such behaviours as ‘abusive, criminal, demonic’ to a specific class.

As Brett Williams argues, despite George Bush’s admonition to shop to save America in 2001, citizens could not because they had too much debt. The neoliberal economy requires its citizens to acquire debt to keep growing. No one can escape it. In 2001, she reported that Americans owed $7.5 trillion in consumer debt. The numbers rise about 130% of disposable income by 2003. The author herself has shared that she understands the burdens, shame and despair once credit became convenient and widely available. Everyone now is in debt. And if people were supposed to be miniature capitalists, Graeber asks, why shouldn’t they be allowed to create money? And actually, use it?

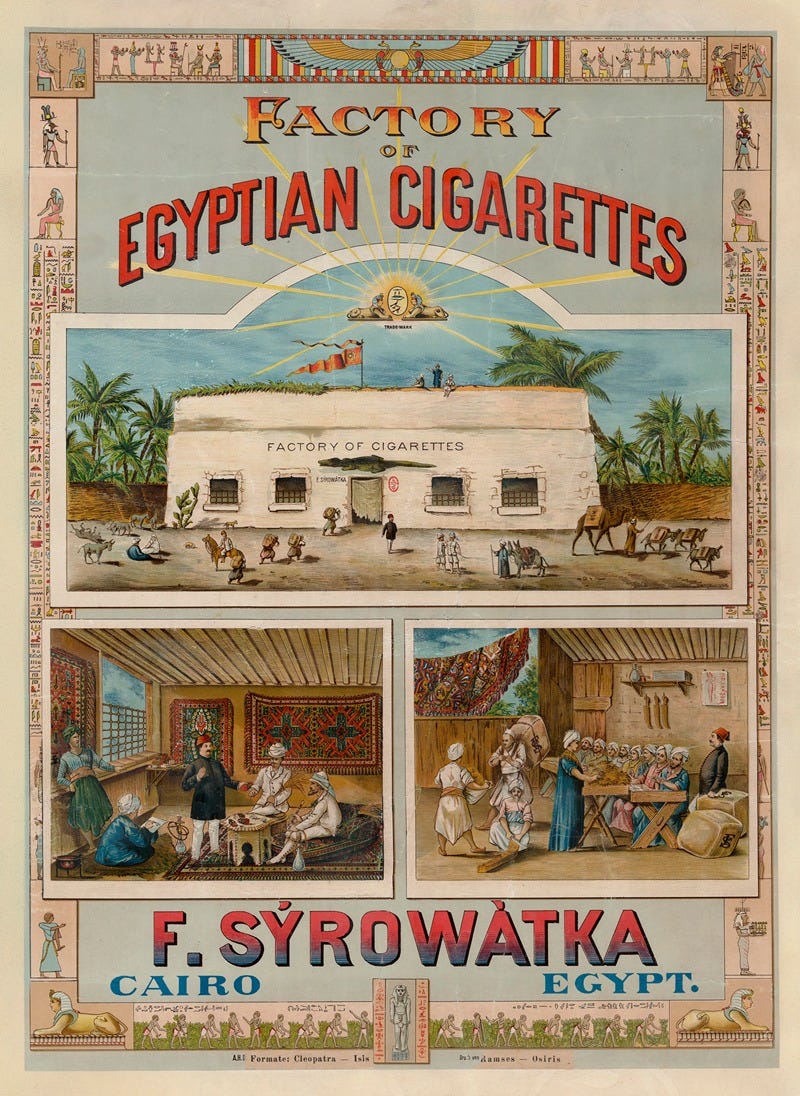

This was the same question that confronted Egyptians from Cairo who took advantage of the social funds available to build their businesses.

From Beneficiaries to Clients

On the larger global stage, the work of Julia Elyachar, demonstrate how neoliberalism enters the networks of the poor. Her long-term work on development, economy and the NGO world exposes the way debt/credit has infiltrated what she calls the ‘phatic communion,’ which are social infrastructures built by communication and action by the social practices, especially of the poor. It is the only way that their needs can be prioritised and met. Unlike social networks that rely on a specific individual’s own connections, phatic communion channels are built in time because of the labour of sociality (visiting, chatting, meeting friends, family, and neighbours) of those that came before. This enables a shared community to form around the same signs, gestures, and meaning made by other people. Thus, the channels remain open to strangers and new entrants because someone else has invested in the labour of translating the meaning, in this case using credit/debt, for successive others to use.

It is this how this channel came to be captured in the new payments technology is the story that Elyachar shares. By the end of the 2000s, the development rhetoric is dead, especially by anthropologists themselved at the end of the 1980s. Even the institutions that granted large-scale, state-managed loans such as the USAID and World Bank, have reduced loans in favour of the informal economy—focusing on the microenterprise and microlending. Elyachar argues that, it is this reduction of state participation and community ‘empowerment,’ an anti-globalisation message, is the goal of neoliberalism itself. The ‘people’ and the ‘poor’ became economic units. Loans are supposed to transform charity into (a negative) into a economic activity (a positive). Thus, needy beneficiaries become clients.

This is how neoliberalism infiltrates our mental models.

The knowledge and phatic communion among the working class Cairo community is ready for new forms of profit extraction. As a counterweight to the motivations by Intel, Vodafone and Visa who use the same research by ethnographers, micro entrepreneurs and people who pose as one, study the channels on how ‘empowerment money’ can be tapped to flow and maintain communities. Though true empowerment did not emerge among her Cairo ‘entrepreneurs’ (the businesses shuttered and could not sustain itself and the men ran the businesses), Elyachar notes that the new field of microlending turns failure of the state into economic success using the social capital of the target beneficiaries. Moreover, microlending and support for the informal economy released the state from its role to provide welfare and address unemployment. In a sense the new state model is one governed by NGOs that enforces new forms of self-discipline through the timely payments of debts. Even the Grameen Bank has not escaped the nets of Monsanto as it has become its “low-cost Pinkertons” a security outfit often hired to enforce contracts and licensing agreements.

NGOs and other International Organisations (IOs) have found adherents for its anti-development model that works outside of the state. This brings with it unseen problems, argues Elyachar. She argues that a new form of “fictitious capital” has emerged in a new global order and one that has little accountability.

Anti-development and the empowerment framework are the dark sides of the neoliberal framework.

Round-Up

How does neoliberalism affect the poor? Our post today examines the new forms of credit/debt movement that occurred in the 1980s, 1990s-2000s. This period marks the move away from the development framework largely managed by the state to one that penetrated communities and individuals.

Neoliberalism is not just a conceptual framework, but a mental model that has infiltrated even the social spaces of the community and down to the individual level. In the United States, the situation is likened to a religion wherein too much credit (whether for greed or need or both) requires massive atonement, purging and suffering endured by individuals and those around them. The debt counsellors and saviours number as much as credit collectors to relieve people of too much debt.

In other parts of the world such as in Cairo, Egypt, credit and debt has shifted from grants to the state to the informal economy. This time charity money has been transformed into capital, ready to empower the citizen. Thus, the entrepreneur was born. Though the results were dismal, microloans are an important component for neoliberal credit economy to operate through the social infrastructure of networks and skirts around the structure of the state. The end is that states are absolved of its responsibility to its citizens while the new governing power—the NGOs and the IOs, offer little accountability in the process. This is ultimately the goal in a neoliberal framework—the reliance on microloans and the self-discipline in payments with onerous punishments for failure.

Hi Readers,

I am preparing to go on the road for six weeks in August until September. Though we are almost at the end of the book, I have not mapped out the final entries but be sure to hang around for the conclusion. It is fast approaching, I promise.

I do not know if I can keep up with my postings as I am going to do a lot of care work and clean up during that period. Be sure to subscribe as I may give weekly personal updates on the chat (via the Substack app) which will be converted to emails. This is one way to keep up with me. I hope to complete Graeber’s work before the end of August.

I will launch a new season studying the history of anthropology, with various books and meanderings along the way. I have been looking forward to it for a long time now.

Enjoy a cooler and rainier summer! I do appreciate it over the punishing heat in early July.

Onward,

Melanie

Recommended Sources:

Atwood, Margaret. (2008). The 2008 CBC Massey Lectures: Payback: Debt and the Shadow Side of Wealth. Audio Recording, July 31, 2025

Atwood, Margaret. (2008). Payback: Debt and the Shadow Side of Wealth. Toronto: House of Anansi Press Inc.

Elyachar, Julia. (2010). Phatic Labor, Infrastructure, and the Question of Empowerment in Cairo. American Ethnologist 37(3): 452-464

_____(2003). Mappings of Power: The State, NGOs and International Organizations in the Informal Economy of Cairo. Comparative Studies in Society and History 45(3): 571-605

_____(2002). Empowerment Money: The World Bank, Non-Governmental Organizations, and the Value of Culture in Egypt. Public Culture 14(3): 493-513

Midnight Notes Collective & Friends. (2009). Promissory Notes: From Crisis to Commons. https://libcom.org/library/promissory-notes-crisis-commons

Williams, Brett. (2004). Debt for Sale: A Social History of the Credit Trap. Philadelphia: University of Philadelphia Press

Find your way around: the book outline

Debt: The First 5,000 Years

Our 2024 read is another highly cited but intimidating David Graeber book! He argues that debt should be the central point in the study of economy and money. He also thinks about creating a humane money system.

Re-read the previous post:

Addendum: Chapter 12 (Part 1): The Gospel of Divine Growth

The evangelical blueprint behind the American neoliberal capitalism of unlimited growth and potential: a two-parent household and a completely unregulated market