Chapter 12 (Part 5): Neoliberalism's New Religion

Neoliberalism fits with the growth of an American Evangelical Right to build its Republic.

If you are new here, we are reading David Graeber’s Debt: The First 5,000 Years. Catch up and join us on Thursdays in 2025. My first slow read here on Substack in 2023 was David Graeber’s The Dawn of Everything. These two books showcase his thesis on the development of humanity by looking at how people organise themselves and their world around human values and choices. Unique among his peers, Graeber still asks the big questions in anthropology.

The New Religion of Neoliberalism

The financialisation of the everyday makes it hard not to think of ourselves as a product, a brand, as a corporation unto itself, and as a machine. Even life is a grind. It is because we must pay our debts—a mantra approaching that of a dogma. Graeber argues that in this season of capitalism, honour has completely left the equation.

Why do you need honour when you have multiple letters, emails, reminders, and legal writ to remind you to pay up! (The Dutch credit score keeps your debt and debt payment on record for five years, like a scarlet letter, even after you have paid up. It affects any future credit purchases, like a house or car loan.) It is this absence of honour that Graeber says that debt acquires its halo of religion. Or allows new frameworks to be overlaid over it.

The Double Theology of Neoliberalism

Graeber refers to double theology as a different order and rules for the debtor and creditor. In a time of a new capitalism in the 1970s, I recast double theology as the parts that make neoliberalism its new branch of capitalism.

One of the ways that neoliberalism has become religion is that it has grafted itself unto ourselves as humans that it is difficult to criticise or disentangle to what we hold so dear—our values, virtues, beliefs, and our very bodies.

Throughout the early modern period of capitalism, we have come to understand capitalism’s relationship to the human body.1

how credit became immoral and illegal due to the hand of the legal courts/state;

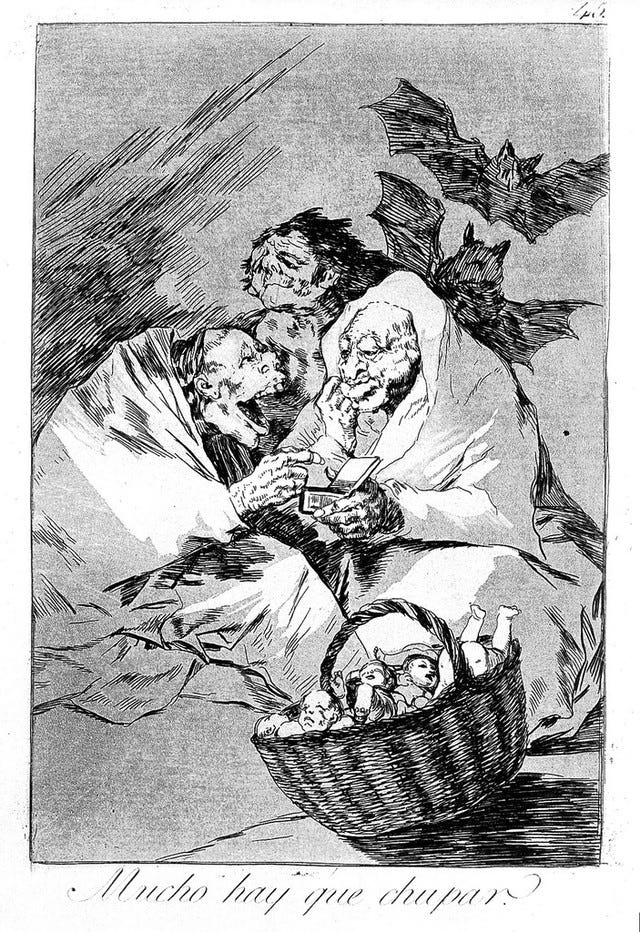

the exercise of human life extraction as a way to pay off debts from the point of view of the oppressed and of the oppressor

In these instances, much of the explanation of capitalism’s parasitism had to do with the imposition of external factors on human life. However, neoliberalism grafts itself from within—so much so that we have internalised capitalism’s principles into life. This is the thesis of political sociologist, Miranda Cooper, as she traces the point in which life, as a separate entity unto itself, merged with the political economy—converging as biopolitics in the United States.

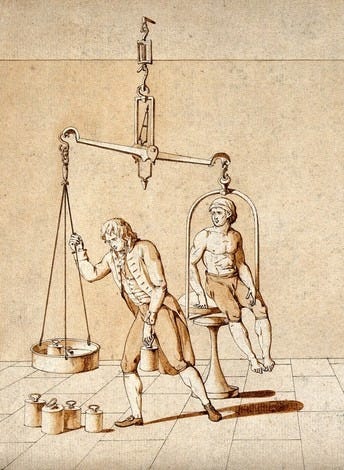

First, U.S. biopolitics requires that life becomes autonomous as a category separate from the other modes in the natural and human sciences. This is necessary because the human body and labour that it exerts becomes a new found commodity to possess value and something to be measured in Economics (see Foucault). As Cooper learns, human biological life becomes the defining wealth compared to other material commodities. This is unsurprising since the 1970s ushered in oil crises and exposed the limits of the environmental resources. However, she found that wealth is limitless with the reproduction of human creativity and the its biological shell. This unfettered growth becomes the singular contingency of growth in the economic balance sheet.

Second, U.S. biopolitics requires the breaking and reordering of the social contract. In the New Deal, the welfare government uses a different form of biopolitics that tracks a human life’s value based on risk, using the tables of actuarial science, to manage a person’s life not just his productive working years but from the beginning to its conclusion. The idea is that there are limits to personal culpability and social/life insurance came to be the governing mechanism of risk redistribution in a welfare state (see Ewald). The redistribution of risk that ensures the maintenance of ‘life expectancy,’ ‘birth rate,’ and the lowering of the ‘mortality rate’ as a gauge of social health came to be the bedrock of the social contract of mutual obligation. A citizens’ duty was to perpetuate the nation into the future. Interestingly, the family is a central piece of this puzzle.

Unfortunately, neoliberalism made reproduction not only as a commodity but as a reserve of value ripe for financialisation. That is, life, its insurance and catastrophes are now a ‘legitimate form of investment.’ The difference is that Cooper says is that it is a more organised system of profiting over unregulated distribution of life chances best described in capturing the value of humanity through its body parts.

Neoliberalism’s Neonate

What better way to encapsulate the new biopolitics than the American Right’s vociferous voice in the protection of the unborn child. As Graeber points out, the rise of an evangelical right accompanied the proliferation of American debt imperialism. Cooper further explained that this connection is not coincidental. The moment that the U.S. got off the gold standard, was the moment that the U.S. entered a ‘superimperialism’ status, a term coined by Michael Hudson, who studied the effects of the costs of the Vietnam War to the budget deficit. The U.S. now became a creator of debt without limit in which no final redemption is possible. This is because other countries enters into a forced loan arrangement because any surplus dollars earned could only purchase U.S. Treasury bonds. The value of the dollar erodes the value of the Treasury bonds as more and more are purchased. However, the Treasury debt is never fully repaid but rolled back again as loan to the U.S. government indefinitely.

In economic terms, then, the very idea of the American nation has become purely promissory or fiduciary—it demands faith and promises redemption but refuses to be held to final account. Its growing debt is already renewed just as it comes close to redemption, already born again before it can come to term. America is the unborn born again.

p. 164, Miranda Cooper, italics mine

The American evangelical comes from a long historical line from the American Christian Republicanism which specifically went against traditional religious establishments and state clergy—a life of free enquiry and immortality under God, remarks historian Mark Noll.2 Unlike its highly hierarchical European roots of the Roman Catholic, the Protestant does not eschew worldly affairs but locates itself at the heart of business and money. Cooper identifies variants of Protestantism like Methodism as espousing a clear concept of regeneration or new birth. The conceptual framework that fuses life, faith and wealth with Republican nationalism fits this period of change since the 1970s.

Neoliberalism and the Evangelical Right converged on principles and this forms the backbone of what would be the divine theory of money creation.

Round-Up

Neoliberalism in the U.S. is a distinct branch of capitalism that fuses a different type of biopolitics linked to the American body. It consists of commodifying human body parts (biotechnology) and breaking the New Deal social contract in order to profit, speculate, and monetise the human body—both for its parts (stem cell) and for its labour value.

New Capitalism will not be complete unless accompanied by a new moral theology and person in the guise of the American Evangelical. This is a distinct American flavour of Protestantism that encompasses faith, nation, money, and the right to life.

Sources:

Cooper, Miranda (2008). Life as Surplus: Biotechnology and Capitalism in the Neoliberal Era. Seattle: University of Washington Press. see chapter 6

Ewald, François (2020 [1986]). The Birth of Solidarity: The History of the French Welfare State. Miranda Cooper, ed. and Timothy Scott Johnson, trans. Durham: Duke University Press. see the foreword of Cooper: Risk, Insurance, Security

Foucault, Michel (1994 [1970]). The Order of Things. New York: Vintage Books. see p. 254 section on Ricardo

Noll, Mark A. (2002). America’s God: From Jonathan Edwards to Abraham Lincoln. New York: Oxford University Press

Find your way around: the book outline

Re-read the previous post:

Chapter 12 (Part 4): Slaves to Credit: Capitalism's New Deal

How did we end up here? We are once again middle-class slaves to credit.

I argue that this neoliberal path is different from the attention of the Chinese state and the corporal body of its citizen with its strict child policy but also much earlier in its history, see Yunxiang Yan’s individualisation in Chinese society or this link, biopolitics and more recently the use of therapeutic language in governance. It sounds like neoliberal governmentality like other scholars will argue but I think has a different trajectory to the Western context. Is China neoliberal? See Isabella M. Weber for an overview but also Donald Nonini who I share a similar viewpoint with.

According to Noll, it has its roots in the imperial wars of the 1740s and the reaction of Americans to the French Revoluiton in the in 1790s. This nonconformist attitude believes that there a protestant is against all forms of submission of mind and opinion (especially the Anglican establishment). see pp. 73-74.