Chapter 12 (Part 4): Slaves to Credit: Capitalism's New Deal

How did we end up here? We are once again middle class slaves to credit.

If you are new here, we are reading David Graeber’s Debt: The First 5,000 Years. Catch up and join us on Thursdays in 2025. My first slow read here on Substack in 2023 was David Graeber’s The Dawn of Everything. These two books showcase his thesis on the development of humanity by looking at how people organise themselves and their world around human values and choices. Unique among his peers, Graeber still asks the big questions in anthropology.

Timeline to Chaos

Nothing makes sense today. There is a missing piece that rivals the social chaos we find ourselves in. This is the next stage of capitalism when everything looks familiar but nothing about it feels the same. The snake has shed its skin once again.

We are in another crisis but it is not as clear-cut as the financial meltdown of 2008. Fortunately, Graeber presents a timeline to help us understand how we got here and how the social contract broke.

The Post-War Boom Deal (1950-1970)

If you are wondering why the Boomers had it good post-War, it was because of what Graeber calls as the tacit agreement which suspended the class war that plagued nations prior to World War II. This was the Keynesian Era, based on the economic theories of John Maynard Keynes, which formed the foundation of Roosevelt’s New Deal in the United States and implemented almost exclusively to industrial capitalist nations. This was the golden day of the welfare state model when social benefits and unions allowed the working class to enroll their children to university, buy a house, and move up the social ladder. Basically, his tenets relied on big government spending, intervention, and reserve control. The idea was to temper the extreme wealth and the further destitution of the lower classes by matching worker’s productivity with subsequent wage hikes.

Graeber hypothesised that the popular movements between the periods of 1945-1975 were battles for inclusion to such a fantastic deal. These movements included decolonialism/nationalist protests and feminism. Political equality, he says, remain toothless without economic parity. That was the unspoken battlecry during that generation. Graeber calls this as the ‘cry for inclusion’ rather than simply autonomy.

No Deal (1970-1989)

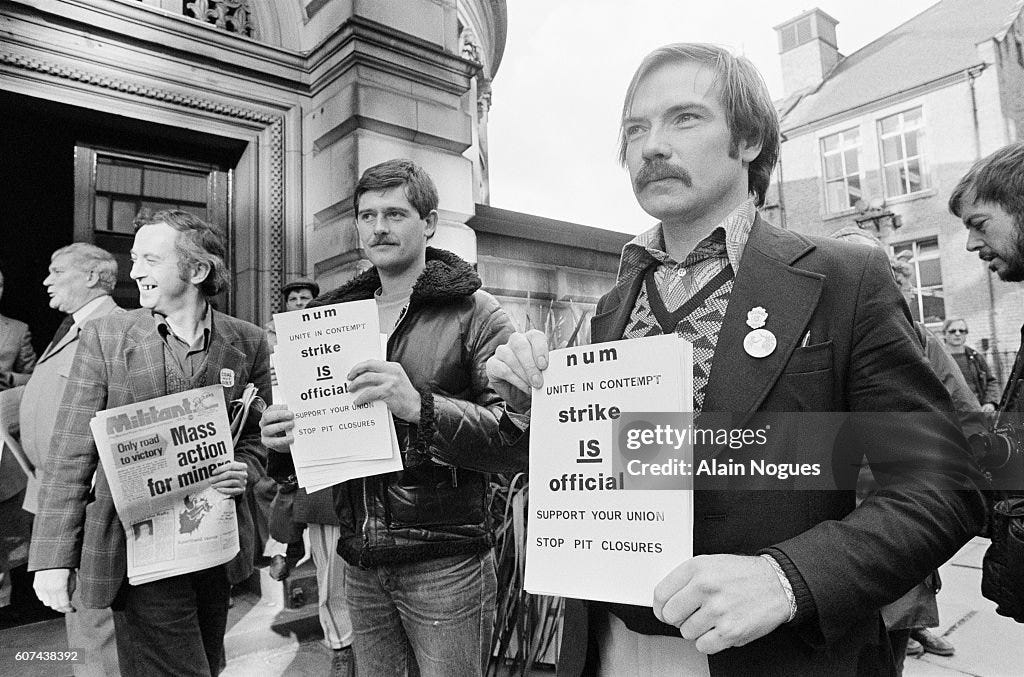

The world is on fire. Vietnam War, getting off the gold standard, the oil crisis, and the credit/debt crisis, stagflation among other things. We were at the height of the nuclear meltdown threat between the USSR and the U.S. It looked like the world was unraveling—and it was. Margaret Thatcher was dismantling the last of the labour unions and shutting all the mines. Ronald Reagan was doing the same in the U.S. This was the last vestiges of national self-sufficiency before it was made expensive and non-competitive against imports and cheaper labour costs overseas. It was the end of the Keynesian era and the social contract. (Something similar happened in the Philippines).

It became apparent that capitalism can no longer afford to give auto workers and steel workers their own house, car, or send their children to college. The wages no longer kept up with worker productivity especially when your competitors had no workers protections or unions halfway around the world. Hypercapitalism requires slavish extraction of value.

New Slave Deal (1990-2008)

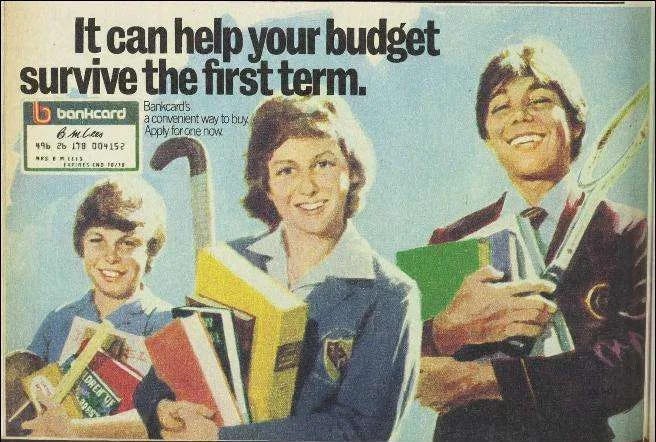

This is the age of speculation as money no longer is tied to gold or any commodity which meant that the surplus of money (i.e. printing endlessly) need to be tamed. If wage increases were no longer assured, then there has to be a way to compensate the employed to keep them working despite the low wages.

One was to make people rentiers themselves. Rentiers were people who lived off other people’s debts, that is benefitting from the increase of interest rates. Virtually everyone is a rentier nowadays. If you carry a credit card or paying off a mortgage or putting your money in some 401(k) retirement account, you are a rentier. You are an investor and encouraging others to borrow. This “buying a piece of capitalism”as Graeber describes is known by many terms, the “democratization of finance,” the “financialization of everyday life,” or its more ubiquitous term, “neoliberalism.”

Since wages were not keeping up with productivity or inflation, one must, inevitably profit from our own exploitation by borrowing. Whether it is from new arrangements like Klarna (a buy now, pay later app), or your neighbourhood pawnbroker, or loan shark if you are desperate. Usury no longer exists in this era.

In the United States, a financial deregulation move was done in 1980 especially on loans to combat inflation. This was called the Depository Institutions Deregulation and Monetary Control Act of 1980. The language of the provisions are obtuse so I leave it up to you to read it out. However, usury laws vary at the state level. Some states have no interest ceiling such as Nevada but its neighbouring state of California have a 7% ceiling. Depending on where you register your lending business, you could invariably charge more, legally. This is why pay day loan companies could charge extortionate amounts and be protected by law. In the Philippines, with a similar no ceiling on interest rates, the court can rule against immoral loans by lending companies.

If you feel like your life is perpetually under the tentacles of capitalism, it is because it is. We return once again to the times of slave conditions but this time disguised as something else. To remain as middle class consumers (with hardly any wage parity), we must become slaves to credit.

The story is unfinished.

It seems like the only escape we have as consumers is religion—a rather uncharacteristic solution but one that has been tested for thousand of years. Next week, we discuss the double theology that emerged from this chaos.

Dear Reader,

I am back after a week long sojourn in Vienna. For those who have subscribed, you received a (double) missive about my trip. Apologies. The Substack app still is not functioning properly. I hope you enjoyed my travel and writing insights and a sneak preview of my next project. It will be fiery and controversial but necessary to salvage anthropology. I expect cancellations (but I am too small a newsletter to even consider this).

In any case, the trip was a personal success. Despite the tropical heat, I had a chance to work, to think, and to write in my notebook without distractions and in an environment that has sheltered academics and thinkers. One can be a Catholic and a scholar in this town. No other city can compare with the material and spiritual treasures that still exist in its architecture and archives.

Onward,

Melanie

Round-Up

To understand the form of capitalism we have today, Graeber proposed a brief timeline to the present. You can find this in the subsection pp. 372-377. In this you find three periods covering the Post-War Boom (1950-1970), the Breaking of the Deal (1970-1989), and the New Slave Deal (1990-2008). The New Deal of Roosevelt formulated in the early 1920s followed the end of World War II in which a class war was averted with protections and assurances of social mobility. This is the much vaunted welfare state model.

The problem is that this deal was only ever going to be possible for a small segment of North America and Western Europe. Capitalism cannot sustain such arrangements with inflation and rising costs from global expansion. It cannot sustain expensive industries (i.e. paying for pensions and subsidising costly mines). Thus, the welfare state model eroded and eventually extinguished.

The form of capitalism we have now is the same but different. We are now party and participants to our own slave conditions (with minimal or highly controlled state support systems). To even attain a semblance of the middle class purchasing power, we succumb to perpetual credit slavery.

Find your way around: the book outline

Re-read the previous post:

Addendum 2 (12.3): Rituals and Returns: China's Tributary Playbook

Why political or economic submission look like generosity in China's tribute logic