Chapter 12 (Part 3): Debt Imperialism: Bank Loans as Modern Tribute

The new tributary order demands debt peonage as part of the loan repayment

If you are new here, we are reading David Graeber’s Debt: The First 5,000 Years. Catch up and join us on Thursdays in 2025. My first slow read here on Substack in 2023 was David Graeber’s The Dawn of Everything. These two books showcase his thesis on the development of humanity by looking at how people organise themselves and their world around human values and choices. Unique among his peers, Graeber still asks the big questions in anthropology.

The Unravelling

In Chapter Twelve, Graeber’s hypothesis that

falls apart and is disproven in the contemporary period. He himself saw how the contemporary period differed from the ancient past. The outset of virtual money or the proliferation of credit did not lead to less militarisation, slavery or debt peonage. Rather, it exacerbated it.

The shape of military might and debt combines to what Graeber and economist Michael Hudson call debt imperialism. This is a specific brand of debt relationship that relies on a political drama played out as a credit-debt relationship. However, its underlying implication as a tributary relationship is of greater interest.

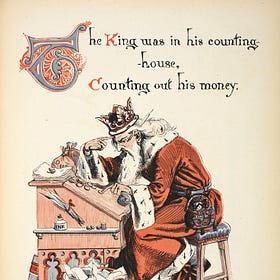

There’s a reason why the wizard has such a strange capacity to create money out of nothing. Behind him, there’s a man with a gun.

p. 364, Debt

The Marxist Heyday of the ‘80s

To understand debt as a form of tribute, we need to understand the American hegemony, both in wealth and power, in the late 70s-80s. The Cold War was in place and the world was divided between the communists/capitalists. Rightly, the Marxist framework was at its height politically, socially, and in the classrooms. Graeber exercises it accurately for his macroanalysis. He argues that the U.S. was the largest patron of credit and, therefore, debt peonage.

Loans as Tribute Payments

Previously, we touched upon the contemporary debt relationship among institutions and countries called seigniorage (profit gained from issuing/selling currency). Graeber bluntly calls this relationship, more accurately, tributary payments. Though contemporary capitalism did not follow the credit/peace:: coinage/war hypothesis, it did return to the Iron Age’s tribute networks. Archaeologist Laura Junker describes tribute as part of the mobilisation of surplus goods or prestige goods for use by the elite or for competitive exchanges in ritual feasting, payments or exchange contexts. This was one way for the chief and his chiefdom to amass their political influence and increase their prestige and social ranking.

If the giver is of lower rank (the vassal), the practice of offering gifts to a stronger and wealthier kingdom declares their allegiance and loyalty.

If the giver is of a higher rank (the patron), offering/returning gifts—or overwhelming the receiver with excessive generosity and overflowing gifts and favours, dampens any potential conflict. (The Kwakiutl potlatch is an example of what status/influence looks like at the village level. Interestingly, other groups had a way to escape this gift-giving oppression, too).

It is the behaviour of the patron that is key to our discussion on credit as tribute. By showering others with generous credit and low-interest loans, the patron attracts other tribute supporters and therefore expands their political influence and authority.

The difference in the contemporary period is much more insidious. Tribute in the form of credit enslaves whole economies. For this post, I look at the American hegemony that falls in our timeline.

US (International Monetary Fund)

The main patronage arm of the U.S. has been the International Monetary Fund (IMF) since after World War II. Though it has gone largely under the radar since the mid-2000s, its outsize influence reached its peak in the late 70s until the early 2000s. It was originally conceived as a counterpoint to the political and economic nationalism of the 1930s (including preventing another U.S. Great Depression). The framework behind this was that by liberalising trading and payments between countries, it would avoid any future crisis as severe as the Great Depression in the U.S. (it did not). In other words, we recognise this as trade liberalisation, or its populist term, globalisation.

The IMF is an outcome of the conference and subsequent agreement forged at Bretton Woods, New Hampshire by 44 nation-states1. Aside from agreeing to peg the world’s exchange rate to the U.S. dollar ($35 per gold ounce), the member states wanted to avoid the competitive devaluations of currency, counter trade protections, and the imposition of exchange controls (see Bordo and James). One way this was regulated was to establish the IMF.2

The IMF works like a credit union in which every member country deposits a tranche of money, which then dictates how much they are allowed to draw from in times of need. The needs can range from insolvency to a fall in export prices or volumes, which can impact a country’s monetary reserves, or as a response to natural disasters and crises. Of course, the largest investor/member is the U.S. (still at 17.42% of the quota), which has veto rights on any decision in the IMF.

Once the dollar was no longer pegged to the gold standard, the Bretton Woods Agreement collapsed. Most member countries floated their currencies according to their market value. The IMF needed to evolve. That new mission is

to monitor market failures

plug shocks from political/economic transition (especially from the fall of various communist regimes)

and manage any import/export payment imbalances

For the longest period since the War, there were hardly any crises. We were giddy with the idea and promise of globalisation (and cheap and accessible credit). Everyone wanted to be a member.

Since its inception, from the original 44, low to middle-income countries were accepted as members. This is where the problem began to escalate. Michael Hudson, an economist, warned that Third World Countries could not pay their debts. The loan and interest payments were supporting trade dependency rather than paying the principal off. The IMF became infamous for imposing austerity programs or ‘structural adjustment’ that taxed labour, increased interest rates, and sold off public infrastructure to the rent-seeking market sector. As Graeber argues, the IMF became the protectors of creditors rather than the debtors.

The Philippine Experiment

The Philippines was a former colony of the United States by accident. Having been part of the concessions upon the defeat of Spain in 1898, the United States were awarded Cuba, the Mariana Islands, and the Philippines.3 Since that period, even after Philippine Independence on June 12, 18981 (from Spain) and finally on July 4, 1946 (from the United States). It did not release the stranglehold of the U.S. and the debt imperialism extended via the structural adjustment policy of the IMF.

What is this policy of structural adjustment?

to be continued

Dear Reader,

I always debate whether I should hold off on publishing an incomplete piece or wait to complete it. My enforced deadline always wins out. I hope that you don’t mind. I rarely know what to write until I start writing. Outlines never seem to work or emerge ahead of time. Other posts are easier than others. Economic ones like these are challenging. So, I elected to continue next week. Now that I know the general direction, I am eager to examine examples that are familiar to us, like the Greek debt meltdown from the news; the collapse of the Argentinian economy; it is with pain that I look back at the tumultuous and difficult Philippine peso devaluation in 1984 or 1986 that put our family’s furniture export business spiralling and the banks calling in for payment.

It seems so far away now, ancient history.

And yet, we return to it over and over again. I look forward to revisiting and understanding what happened during that period. Ironically, today is Philippine Independence Day. Traditionally celebrated from 1898, we had one year of freedom when the Spanish left abruptly and the Philippine-American War had yet to start. Perhaps, that is a much more romantic commemorative period rather than the Fourth of July in 1946, when our political independence was finally realised.

Independence may be declared, but we are still bound by the yoke of debt. I highly recommend Michael Hudson’s Killing the Host, which explains what is wrong with our system and how we can escape debt.

Onward,

Melanie

Round-Up

The collapse of David Graeber’s hypothesis that peacetime promises extensive credit is partly true. We have an excess of (free) credit, especially after World War II, when democratic nations rebuilt their economies. However, conversely, credit has been guaranteed by the bullet. Military and credit converged.

We can refashion Graeber’s hypothesis into the idea that credit/debt can be seen as tribute payments. A tribute relationship underlies the banking credit loans approved by the International Monetary Fund (IMF)—in which the patron amasses more willing vassals, political authority, and influence. The vassals, though willing, accumulate so much debt that they are subject to conditions of debt peonage. These conditions are what we call ‘structural adjustment’ or the policy recommendations of the IMF. These terms are imposed as a stipulation of borrowing additional loans and were understood as a guarantee that the borrower could pay it off. Such terms, like the devaluation of the currency against the dollar, mean that a country sinks even lower as it tries to make payments of the interest, never being able to fully pay off the principal.

We shall dive deeper into what it means for low to middle-income countries in the late 70s to mid-2000s.

Sources:

Junker, Laura. 1999. Raiding, Trading, and Feasting: The Political Economy of Philippine Chiefdoms. Honolulu: University of Hawai'i Press.

Hudson, Michael. 2015. Killing the Host: How Financial Parasites and Debt Bondage Destroy the Global Economy. California: Counterpunch Books

Find your way around: the book outline

Re-read the previous post:

Chapter 12 (Part 2): The U.S. Dollar: Backed by Power, Not Gold

The apogee of hypercapitalism is to represent a single currency like the U.S. dollar as the world's money backed, not by gold, but by a military industrial complex like the U.S. government.

Today, 191 countries are members except Cuba (which withdrew in 1964), North Korea, and Taiwan (which is blocked by China and listed as its province). See the IMF site.

This international coalition ushered in a hopeful pan-national movement that similarly established other global institutions such as the World Bank, the United Nations, and the World Trade Organization.

There was also a payment of 20 million dollars to Spain as compensation for the property and infrastructure in the Philippines.