Chapter 12 (Part 2): The U.S. Dollar: Backed by Power, Not Gold

The apogee of hypercapitalism is to represent a single currency like the U.S. dollar as the world's money backed, not by gold, but by a military industrial complex like the U.S. government.

If you are new here, we are reading David Graeber’s Debt: The First 5,000 Years. Catch up and join us on Thursdays in 2025. My first slow read here on Substack in 2023 was David Graeber’s The Dawn of Everything. These two books showcase his thesis on the development of humanity by looking at how people organise themselves and their world around human values and choices. Unique among his peers, Graeber still asks the big questions in anthropology.

Magical Money

In our last post, we explored how money seems to possess magical properties. Two reasons we have outlined are the complex way it emerges seemingly out of nothing, or more accurately, (1) after opaque institutions like the Fed Bank conjure them up. Tah-dah—we have money.

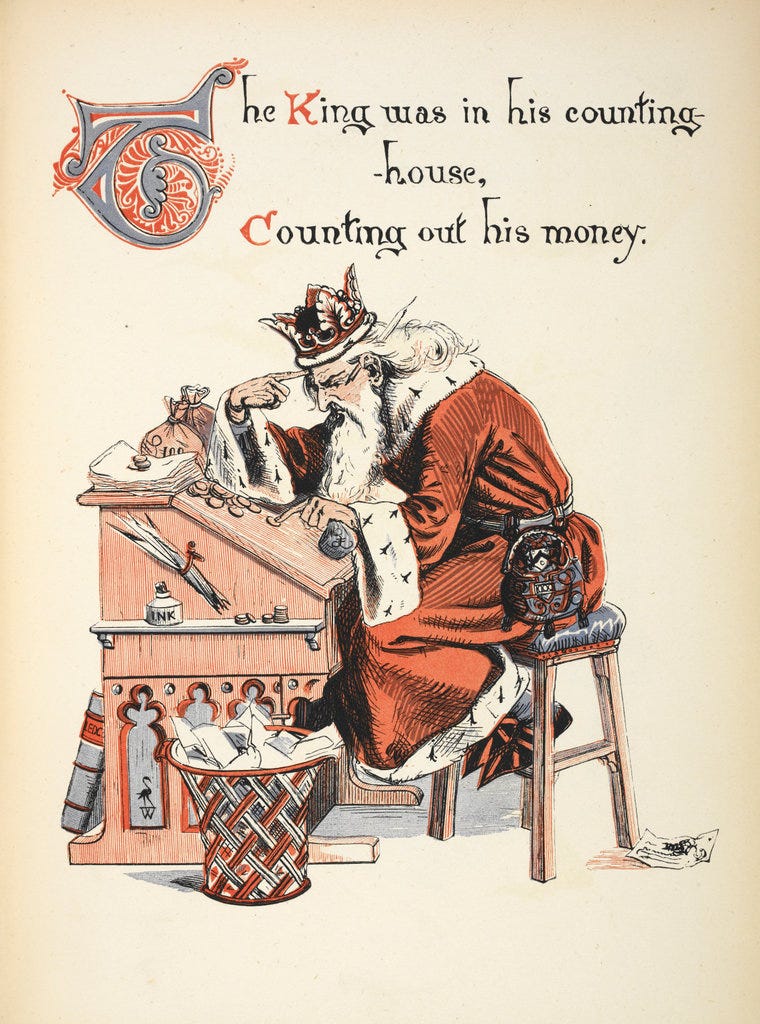

(2) Another way that money remains a fascination is its link with gold. We have had a strong association between valuable metals like gold and silver as placeholders of exchange value. Thus, stories such as buried gold reveal our deep desire for what they represent—untold wealth.

So, what happens when money is no longer linked to gold? What did it reveal? A contemporary nightmarish scenario hidden from view, argues Graeber. This is the frightening side of money magic.

There’s a reason why the wizard has such a strange capacity to create money out of nothing. Behind him, there’s a man with a gun.

p. 364, Debt

Falling off the cliff

What happens when paper money is decoupled from a culturally accepted standard of monetary value, such as gold or silver? Nobody knows. We are living it and we can only surmise its effects in hindsight.

One effect is the reversal of Graeber’s twin hypothesis on money and credit.

He dedicated chapters 8, 9, and 10 to discussing the specific scenarios across cultures and time periods. I have argued that his evidence is thin, selective, and inconsistent, but compelling, nonetheless. It has some basis. War, indeed, required ingots to pay for army personnel and a bureaucracy to implement that. Indeed, it is a chicken-and-egg situation: conquests, especially of mining territories, are necessary to fund the military.

This changed during the European Middle Ages when mercantile capitalism developed new accounting tools to facilitate trade and credit. It became more and more acceptable to represent money in paper form (despite the Church’s designation of the practice as sin). Nevertheless, credit/interest from rich merchants became intertwined with valuable metals that powered the military and war in the region.

By the time we reach the early modern period of 1788, we find the French royal court almost bankrupt. Some historians attribute these to war spending decades previously (especially the U.S. Revolutionary War), while others contradict this. Nonetheless, the coffers were exhausted. The proposed tax reform by the court inadvertently ushered in the French Revolution.

War—on Credit

Whether credit or cash, Graeber argues that the U.S. government is teetering to the same degree as the French Royal Court. Except today, the U.S. is the global superpower with its money as the exchange value for everyone else.

After Nixon’s announcement, everyone is stuck with the U.S. dollar as the only global exchange value.1

It is all in our best interest to prop it up, as Graeber says. Unfortunately, in doing so, we are propping up the war economy that Nixon’s dollar-gold decoupling was for. A report by Keith B. Duke of the Army War College computes direct military costs as $108 billion, up to as much as $750 billion if social, administrative, human resources, and inflation are included. In his report, he noted that the U.S. has a tendency never to pay off the principal amount and thereby incur very high and extended interest rates: ranging from 37 percent on the Civil War, 42 percent on World War I; World War II and the Korean War were pegged at 50 percent and he assumes the same figure for the Vietnam War. Based on this, he estimates that the U.S. was paying $75 billion in interest alone.

Graeber offers similar pronouncements about the pitfalls of the U.S. dollar as the sole monetary exchange. The rest of the world has little choice but to buy U.S. treasury bonds (because we can no longer exchange our U.S. dollar reserves for gold as we used to be). This, in effect, becomes (war) loans in which the U.S. will forever pay interest but never the principal. This is a debt that can never be repaid.

Graeber goes so far as to say that these are tributary payments; economists call it seigniorage. Ironically, Graeber pointed out that countries that hold the most dollars are under some form of U.S. military occupation, like Germany, Korea, Japan, including OPEC countries like Saudi Arabia, in which the dollars are used to trade petroleum. He even goes on to hypothesise that Saddam Hussein, who tried to switch to the Euro in 2000, was invaded. True or not? But it is a wild idea.

Magical money consists of hidden and hard-to-understand properties aside from its exchange value.

supporting the U.S. military war project

the Fed can conjure up paper money and earn interest from it through selling treasury bonds

uncoupling it from gold now means we rely our trust on the U.S. (military) government for better or worse

As I write this, it is bizarre how contemporary capitalism has evolved in our period. With the decoupling of gold and fiat money, war now runs on credit (Treasury Bonds) and interest payments that will never be fully paid.

Will the white rabbit appear from the hat? Never, I hope, if we want to avoid a total collapse.

Round-Up

We continue with our discussion on the magical properties of money, particularly on the state of the U.S. dollar. We are now living in contemporary capitalism wherein fiat money (U.S. dollar) has been thoroughly decoupled from precious metals. We have broken off from a long-standing order of moving metals in country-wide trading. What we have before us is a condition in which loans, in the form of Treasury Bills produced by the Federal Reserve Bank, are inevitably purchased by other countries and citizens to fund the U.S. government’s war economy. Credit and war are nothing new in the modern period. However, to rely on a single currency as an exchange value means we are entrusting the world economy to the strength and reliability of the United States. This is the apogee of hypercapitalism.

Find your way around: the book outline

Re-read the previous post:

Chapter 12 (Part 1): The Magic Money of Capitalism (and the Missing 9/11 Gold)

Money is magical because it appears/disappears out of thin air.

The Economist reported that Putin and other BRIC countries were creating another exchange currency. Currently, Putin is reversing his position with Trump seated in the Office.