Chapter 11 (Part 6): The Paradox of Freedom and Debt in Western Capitalism

The concept of freedom/debt is the two distinctive features of Western capitalism: the market as freedom paid on the backs of indentured service, free labour, and/or slavery

If you are new here, we are reading David Graeber’s Debt: The First 5,000 Years. Catch up and join us on Thursdays in 2025. My first slow read here on Substack in 2023 was David Graeber’s The Dawn of Everything. These two books showcase his thesis on the development of humanity by looking at how people organise themselves and their world around human values and choices. Unique among his peers, Graeber still asks the big questions in anthropology.

Dear Reader,

We just memorialised eighty years of war and liberation last Monday, Bevrijdingsdag.

There is a practice here of gathering in public spaces with friends and family (children included) to chat, have fun and memorialise the day.

I am glad we are not forgetting the cost of freedom. Interestingly, my post today uncover what freedom really entails in our current economic system. Read on.

Onward,

Melanie

The Origins of Western Capitalism

In Part IV of this chapter, Graeber asks: what is capitalism? More specifically, what is modern capitalism? To trace what is modern is a difficult project. However, it is clear that what we recognise as ‘modern’ and ‘Western’ capitalism is the British strand of capitalism. Based on the sources of Graeber, it appears that of all the forms of capitalism, the island nation grew to be more dominant than the continent, which all started from a mercantilist form of capitalism.

Partly, England’s version of industrial capitalism ultimately stems from two factors that we have discussed so far:

the legalisation of interest (the punishment of debt and the rise of debt prisons)

the enclosure movement (a dominant economic perspective can be read here)—summarised as a property reorganisation and an efficiency movement

The critical turn to England’s dominance of capitalist form is what I call the emergence of the floating population from these two decisive junctures. I borrowed this term from China’s similar phenomenon as it transitioned to a market economy in the 1980s. Previously, every member of the Chinese population was tied to their place of birth, much like how the European medieval period operated. Once an adult of working age, every person was either assigned to work on farms/communes or in government-owned factories. This depended on whether you were fortunate enough to be born in a rural or urban area. Once their communist occupations were eliminated, a huge swath of the population, largely from the rural areas, migrated to the cities for work.1

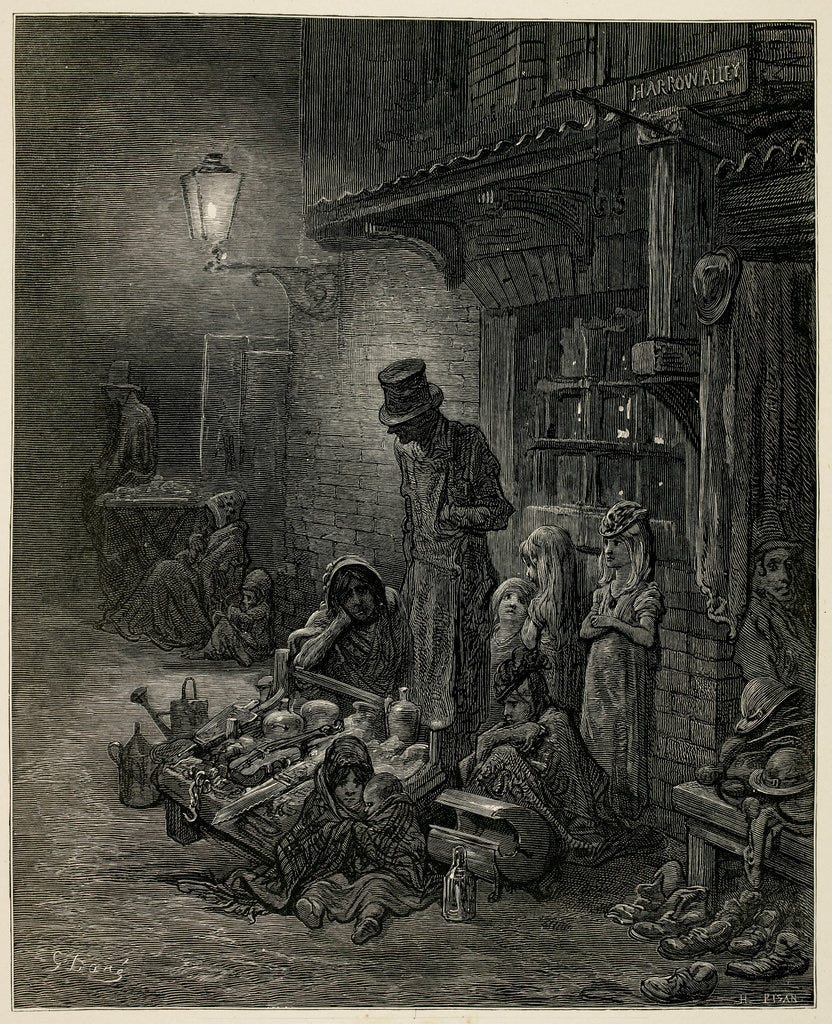

It is uncanny that a floating population occurred in two cases in two different periods before the expansion into industrial capitalism! In England, this floating population were suspected to be criminals and vagrants—separated from any relationship to land or lord—it was understandable to label them as such. It was easy to be punished for being poor and going into debt without fixed identities.

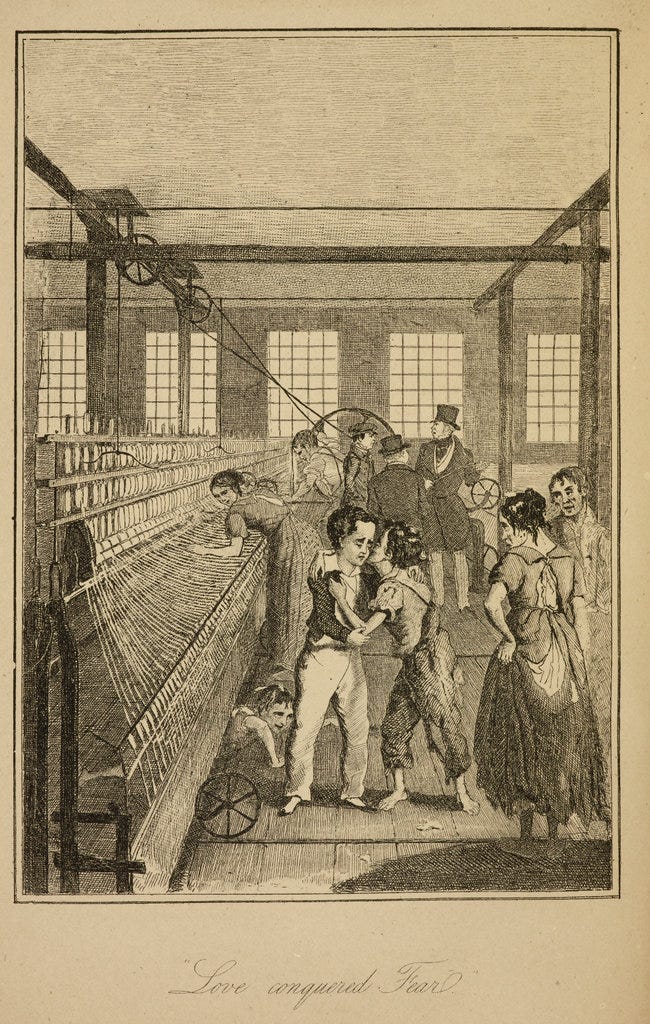

It was also predictable that this floating population would become the malnourished labourers of the Industrial Revolution. A freed labour—freed from the land—is what Graeber argues as the basis for a new understanding of modern capitalism.

Not Class: Freedom/Debt Categories

How do we understand capitalism from a credit and debt system? Well, Graeber raised a fundamental characteristic of capitalism—that it relies on free(d) labour. That is, a population subject to several degrees of indenture, including debt peonage and slavery.

Starting from our baseline date of 1700, then, what we see at the dawn of modern capitalism is a gigantic financial apparatus of credit and debt that operates-in practical effect-to pump more and more labor out of just about everyone with whom it comes into contact, and as a result produces an endlessly expanding volume of material goods.

p. 346

From this perspective, contemporary capitalism, borrowing from Bruno Latour, has never been modern. It has always been modern.

How did this happen? In his network approach to analysis, Latour provides a framework that consists of both tendency to combine hybridised and purified or distinct knowledge fields (e.g. nature/society). Latour envisions this as an x and y axis that I slightly modify and interpret as also going across time. Though he meant this as a criticism between the general insistence of dualities of nature (natural sciences) and culture (social sciences), I am appropriating it here to explain

why it is difficult to trace the modern and non-modern in capitalism.

why it feels that capitalism has always been contemporary and repetitive

Latour’s model tracks the development of what we recognise as modern capitalism as a throughput into the past, thanks to the push/pull of different disciplines and areas.

The result is that the past seems remarkably modern and hybrid, consisting of a bizarre admixture of faith, foreign conquests, yet recognisable as a recent phenomenon. This is why when you read about the conquistadors, the stock bubbles, and travelling merchants, it is as if you are reading about today.

Labour and Slave Relations: cycle of debt and slavery

The jarring time lag of the past in the present is why it feels that wage labour is akin to slavery. The line is thin. Immanuel Wallerstein calls it the second serfdom, in which the landowner is no longer producing for the local economy but gearing his supply towards a world market.2 The goal is not towards subsistence but as a commodity on the world market. This is only possible with the hand of the state. Compounded with war and commerce, the results are what we recognise as characteristics of modern capitalism.

At the top of the chain are the bankers far away, such as in Genoa, who, with their accounting prowess, bankroll trades overseas, fund the royalty, and the church, using the tip of the sword to get their way

At the middle of the chain are the Spanish conquistadors, who in their initial goal of finding a cheaper way to China, unleashed military might that extended debt relations further down the chain to the local population

The middle chain also consists of the local population, whose multiple brokers take advantage of the debt symbolon and commercialise it to draconian results

The top-down chain reflects the perspective of the duality of freedom and debt and how it is hopelessly intricately tied. Though it appears that the conquistadores had it good (holding the whip), they have their debt of shame to hide. Freedom and debt exist simultaneously in the same dimension. Capitalism possesses little moral force except for debt. And the results can be catastrophic.

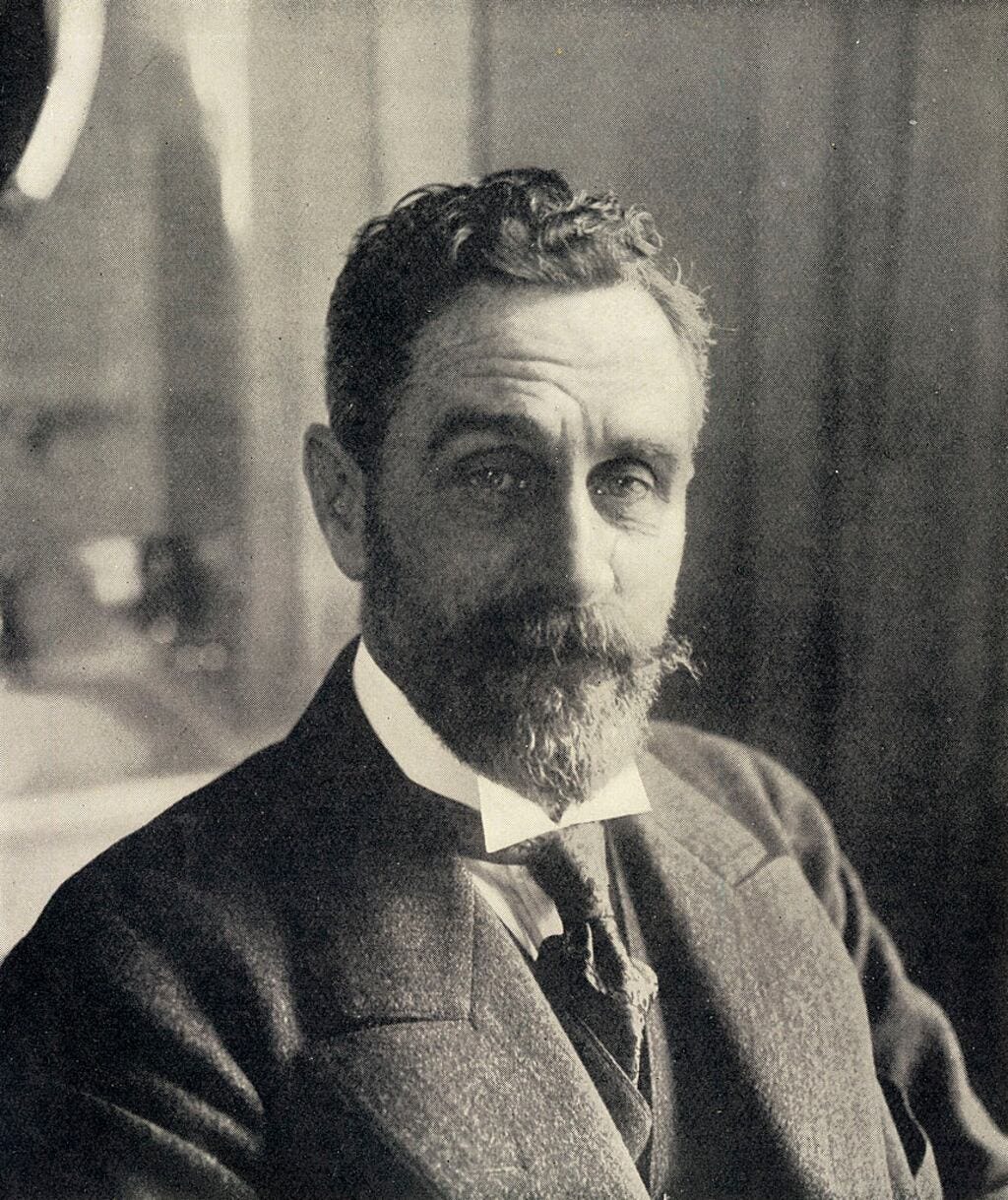

This was why the Putumayo scandal of 1909-1911 was met by the British general public with disgust and astonishment. It exposed the forced labour endured by the Huitoto and Boras Amazon Indians (among others) who harvested rubber under the Peruvian Amazon Company to make tires. It revealed the price of the capitalist enterprise and freedom with slave labour.

The Indians themselves were uninterested in trade or working to create commodities. Hence, terror tactics—rape, torture, mutilation, cruxifixion, bodies hacked to pieces, flogged, and used for target practice—were the only ways for the Indians to accept forced labour and indenture. These were documented by Roger Casement, a diplomat, who was sent by the British to investigate the atrocities. What he found was the banality of cruelty.

While the physical torture was the focus, little attention has been given to the forced debt relation that haunted human relations:

The root of the whole evil was the so called patron or "peonage" system—a variety of what used to be called in England the "truck system"—by which the employee, forced to buy all his supplies at the employer's store, is kept hopelessly in debt, while by law he is unable to leave his employment until his debt is paid . . .The peon is thus, as often as not, a de facto slave; and since in the remoter regions of the vast continent there is no effective government, he is wholly at the mercy of his master.

p. 349

It turned out it was the Spanish conquistadors’ experience all over again, four hundred years later. The agents and overseers themselves were mired in debt to the Peruvian company that commissioned them, who in turn were funded by London investors.

…the end product was the same: human beings so entirely ripped from their contexts, and hence so thoroughly dehumanized, that they were placed outside the realm of debt entirely.

David Graeber, p. 347

Freedom: is a way out possible?

It seems there is no way out of a three-chain debt cycle that reproduces the worst of the capitalist system. One way out that Graeber noticed was the direct payment exchange promised in the wage labour system. Again, this belief, he says, assumes that from a position of uncertainty, the wage labourer will become better paid, receive a regular pension and such. However, it seemed that in the Medieval Age, he noted that there was even more of a possibility that a peon or apprentice would pay off their learning in a year and be able to accumulate resources to support their family.

He continues that this was not possible when it came to the proletarianisation of the floating population in England and elsewhere on the continent. These industrial apprentices would never reach a position to support their families because cash was not readily available. Workers were given vouchers for goods with which the employers had some form of arrangement or owned. Workers were also allowed to keep waste from their workplaces, including timber, if they were dockworkers. This gives a dimension to the term working poor in which the employed had to find ways to survive until the money showed up. It was fairly typical not to pay workers immediately.

That is, until 1800, when the government was able to stabilise its finances and pay its own workers regularly. The workplace benefits that were in practice became workplace ‘pilfering.’

It now appears that freedom can indeed be attained by the absence of debt when one’s labour, or any commodity for that matter, can be easily swapped with cash, a one-to-one exchange. This is what Graeber calls as a perverse form of freedom built on the virtue of self-interest.

Round-Up

We continue with the investigation into the origins of Western capitalism. This time we looked into the key feature of capitalism that takes us from the pre-modern up to the modern period—the availability of free(d) labour.

In England, two factors converged: the enclosure movement and the legalisation of interest, contributed to the loss of land and the exodus of the population from the rural areas. This floating population, akin to China’s 1980s worker exodus to the cities as the first factory labourers, were considered vagrants and criminal elements.

This free(d) population constituted the factory labourer whose status is no different from slaves that we have seen hundreds of years ago. Few were paid regularly in cash, and they epitomised the working poor who were paid irregularly, received tokens or goods as compensation, forced to work and were constantly in debt to survive. This would change by the 1800s when cash payments became instituted by the government bureaucracy. Ultimately, this cemented our current belief and practice that direct cash exchange was more virtuous than being in debt.

Two alternative values emerge here than a class analysis. Graeber argues that if we use freedom/debt to define modern capitalism, we will find that:

the past is eerily like the present—a Möbius strip of slavery and wage labour

self-interest and the absence of credit are virtues in Western capitalism

Sources:

Goodkind, Daniel and Lorraine West. 2002. China’s Floating Population: Definitions, Data and Recent Findings. Urban Studies 39(12): 2237-2250

Latour, Bruno. [trans. Catherine Porter] 1993. We Have Never Been Modern. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Taussig, Michael. 1984. Culture of Terror--Space of Death. Roger Casement’s Putomayo Report and the Explanation of Torture. Comparative Studies in Society and History 26(3): 467-497.

Find your way around: the book outline

Re-read the previous post:

Chapter 11 (Part 5): The King is in Debt

Credit morphed into joint-stock companies in the West: financing wars and fueling early modern financial crises

The difference is that location defines the rights and benefits of the Chinese population. Thus, moving essentially meant the loss of benefits such as schooling for your children or receiving any housing benefits from the state.

In his first volume on the modern world system, Wallerstein describes serfdom as a labour arrangement in which the landowner

produces for the local economy

gains his quite localised power when the central authority is weak

he enjoys some luxuries and supports the costs of warfare.

Thanks for reading and the support!