Chapter 11 (Part 5): The King is in Debt

Credit morphed into joint-stock companies in the West: financing wars and fueling early modern financial crises

If you are new here, we are reading David Graeber’s Debt: The First 5,000 Years. Catch up and join us on Thursdays in 2025. My first slow read here on Substack in 2023 was David Graeber’s The Dawn of Everything. These two books showcase his thesis on the development of humanity by looking at how people organise themselves and their world around human values and choices. Unique among his peers, Graeber still asks the big questions in anthropology.

Dear Reader,

I am recovering from the busy Lenten season that culminated in Easter. I had not realised how the medieval Christian calendar is tough training for believers. And it never stops! We are in a long season of Easter—fifty days of joy, longer than the season of sorrow. The penultimate bookends are the Ascension (Hemelvaartsdag), Pentecost (Eerste Pinksterdag), and Whit Monday (Tweede Pinksterdag), three holy days on May 29, June 8 and 9 that remain official Dutch holidays. It remains surprising but encouraging for someone like me!

In preparation to return to the feasting state, I’ve returned to my discounted shopping routine. This is essentially selecting products destined to die on the shelves (or in the bins!) And I have figured out when the largest number of products becomes available. It is rare, but I have scored fabulous French black hens (which I suspect few people purchase as there are only two chickens at any one time in the chiller) that made wonderful soup and boiled chicken—ala Singaporean Hainese chicken style. Dunk in a pot of water (after pre-boiling and discarding the first 5 minutes), and in twenty minutes you get wonderful and tasty meat with just salt and ginger as base flavour.

The discount ranges from 25% up to 35% off the regular sticker price. So the fish becomes affordable and I can taste some new products I would never have bought—such as peanuts and the coated nuts which are very tasty! All of this for a 39 Euros final retail price instead of 51 Euros.1

So yeah, the marketing works on me, but I feel like I am getting much more out of it as shoppers shy away from the discount tag, thinking the products are close to perishing. Not true. They last even a few days after purchase or longer. I’ve tested them and they are fine!

All of these products have now been consumed (very good!). *Burp* I’ll probably write something about this later on, now that I have figured out where other dry goods also go to die.

Onward,

Melanie

The Origins of Capitalism

It has occurred to me now that we are on our third post on the evolution of financing and credit, that Graeber has been tracing the origins of Western capitalism or industrial capitalism.

Graeber specifically points out the Christian roots in Part Three. In that post, he argues that self-love (think: selfishness or self-centredness) transforms into self-interest (the quantified expression in accounting). The link of how that happened is unclear and unanswered, but the similarity, as he pointed out, leaves little doubt that self-interest, as in the self and its link to interest as profit, is one and the same.

However, by Part Four, we get one strong reason for the acceptability towards this shift—and that is, the hand of the state. The courts, more precisely. Credit, once a practice that supported mutual aid to neighbours and friends, has now become criminalised. Self-interest, in the form of direct cash payment or direct exchange, came to be seen as a nobler measure of character.

Today, we look at the next step towards full financialisation in the creation of paper currency and credit instruments.

The Abstraction of Money

Graeber has been developing his thesis that credit as a mutual aid practice must be eradicated. We have seen how the debt prisons penalised poor people and people without access to currency. Once the symbolon of credit fully separated from mutual aid, it became empty, ready to accept new meanings. In this case, it can materialise as money.

Graeber noted that in China, credit materialised as paper money. Meanwhile, in the West, he argues that credit came in the form of stock markets.

War, Buillion and Credit

Remember when Graeber argued that the time of currency indicated war and the time of credit indicated peacetime? That was his exploration in The Axial Age. There is a case to be made that precious metals were a prerequisite to fund armies. Indeed, that was the perennial problem. There was a shortage of gold and silver as metal currency that could circulate among the general public. Hence, much of it remained in the leader’s hands and was predominantly used as wages for armies. The evidence was strong in the Mediterranean but unremarkable in India and China.

The creation of credit as money enabled three things:

it allowed the Kings to borrow and enter into debt

it created paper currency since the bankers floated these debts at a discount to the general public

Of course, this vellon currency, as Dennis Flynn calls them, did not eliminate the buillion but it backed these debt bonds that earned interest for the holders. In Spain, gold and silver were excised from wide circulation. Its proxy became copper coinage and paper. The latter originated from regional fairs in which the bills of exchange were produced indiscriminately and exchanged freely in different cities such as Genoa and Antwerp. Bankers practised what we call today as fractional reserve banking; in their case, it was extending credit three times what they had in reserve. This is one monetary reason that explains the price revolution in Europe. This is in contrast to the explanation of the trade and metals interaction that resulted in the persistent inflation in the economy.

The King is in Debt

In Graeber’s early formulation, the king (or queen) is above any debt. After all, people give him or her gifts and are not expected to return any gift except by precedent. Of course, when it comes to money, the king is always in debt, not to his subjects, but to the minor royals and now the bankers. The engine, of course, is war.

…‘the whole Art of War is in a manner reduced to Money’, so that ‘that Prince, who can best find Money to feed, cloath, and pay his Army, not he that has the most Valiant Troops, is surest of Success and Conquest’—the need to fill the gap was to put it mildly, urgent. What to do? With means of repayment increasingly non-existent, and a range of short-term expedients already tried, the obvious answer was long-term borrowing: the beginning, in effect, of the funded (aka national) debt.

England was in the midst of the Nine Years’ War following the accession of William and Mary in 1688. Unlike the continental model of Banks, the Bank of England was specifically organised to lend to the state. Founded in 1694, through a joint stock bond model, the bank offered subscriptions on the 21st of June with a target of £1.2 million.

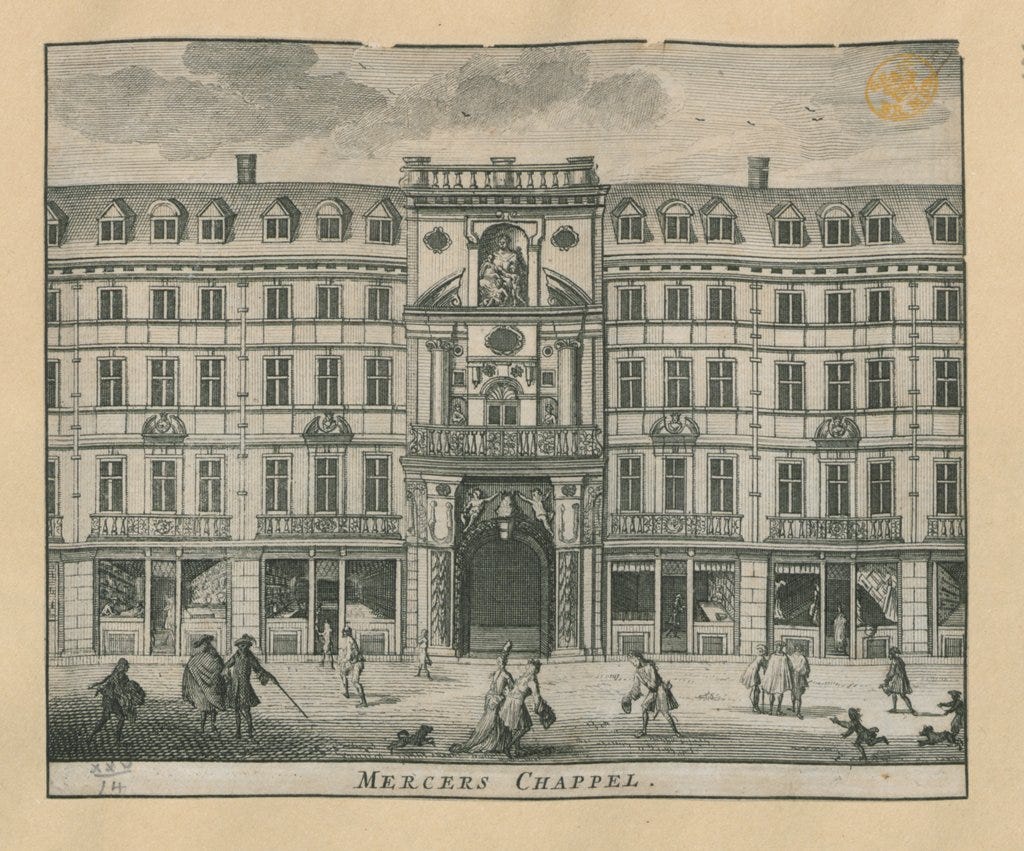

‘The Commissioners for the new Bank came this morning to Mercers’ Chapel, where the books were opened,’ noted the dogged chronicler Narcissus Luttrell on Thursday, 21 June 1694. ‘’Tis said,’ he added, ‘the subscriptions already amount to £300,000.’ Luttrell was right: the capital-raising process for the putative Bank of England was off to a cracking start. In addition to King William and Queen Mary (jointly contributing £10,000, the maximum permitted), other first-day subscribers included the first lord of the Treasury (Lord Godolphin, £4,000), a clockmaker (John Ebsworth, £1,000), a salter (John English, £500), an apothecary (Nicholas Gambier, £600), a host of merchants, and a ‘gentleman’ from ‘the town of St Albans in the county of Hertfordshire’ (John Gape, £500). The following Tuesday a friend told the political philosopher John Locke that he had subscribed £300 – which, Locke then informed another friend, ‘made me subscribe £500’ – while even before that, on the 25th, one of the opponents of the new institution had faced up to painful reality. ‘I am informed,’ the Duke of Leeds wrote from his Yorkshire fastness to his London bankers, ‘That subscriptions to the Bank do fill so fast, that their is at this day near 700’000 subscribed, so that it must now nesesarily be a bank. I therfore desire that you will subscribe foure thousand pound for mee …’ The overall target was £1.2 million (25 per cent payable in cash), and it was reached at Mercers’ Hall in Cheapside on the tenth day, 2 July, with the last of the 1,268 subscribers being Judith Shirley of Preston in Sussex, staking a modest £75.

prologue, David Kynaston

Though the Bank of England continues to exist today, this was not the case with the Banque Royale in France. It was organised by John Law, who created a bank that absorbed all the French colonial trading companies and the Crown’s debt. Unfortunately, it all crashed due to excessive printing of shares, banknotes and speculation. The bubble burst in 1720. Apparently, trust in the king was not enough to stem the thirst for profit and interest.

This was a perennial problem with credit bonds and the development of stock markets. It operated like a casino with futures prices being traded until the prices collapsed, similar to a bubble.2

In London, several other joint-stock corporations formed as part of one colonial venture or another. One of these was the South Sea Bubble of 1720, which was an overvaluation of shares of a future monopoly trade of slaves into Spain. The trade began in April of 1720 at £350, reaching as high as £950, peaking at £1050 before crashing to £124 in December. None of the purported companies or trades occurred. It was only through legislation, again, the hand of the state, that regulated and restricted the organisation of joint-stock companies. The law limited these for fundraising for the construction of turnpikes and canals in Britain. In France, legislation eliminated paper money that holds French government debt.

Once money can take the form of paper, or in this case, credit, the results take the characteristics of what we recognise as the early modern financial crisis.

Round-Up

Credit effectively became money when it was fully excised from its human practice of mutual aid. As a blank canvas, it could take on properties of money. It can appear as paper money, as was in China. But in the West, it morphed into a debt bond or bill of exchange paper. This was not new, as banks had existed and bills of exchange were present in merchant fairs and used in trading.

What was truly unique for this period was the formation of a formal association that could lend to the head of state or the king. (This was similar but also different to the Italian city-states in which merchants became heads of state themselves). However, these early modern banks were joint stock organisations that relied on multiple subscribers to fund them. The debt guarantee stems from the king himself, who is indebted and yet requires financing for wars. Paper credit as money led to the popularity of joint stock companies that operated like casino—with high profits but terrible losses.

This model prefigures the perpetual crisis of late capitalism.

Sources:

Flynn, Dennis O. 1978. A New Perspective on the Spanish Price Revolution: The Monetary Approach to Balance of Payments. Explorations in Economic History 15: 388-406

Kynaston, David. 2020. Till Time’s Last Stand: A History of the Bank of England 1694-2013. London: Bloomsbury Publishing

Find your way around: the book outline

Re-read the previous post:

Chapter 11 (Part 4): The Virtue of Self-Interest

How credit/mutual aid was villainised and self-interest became the moral high ground

It was not just paper that could be manipulated as money. The everyday folk also manipulated metal. Britain was suffering from the high value of silver around the 1690s. British coinage was worth less than the silver that it contained, so people clipped off the coins to keep some of the metal and continue to trade in the full value of the coin. As a result, pure silver coins disappeared from circulation. Stamping a coin at its exact value resulted in people hoarding the high-value coins, effectively keeping them also out of circulation. The low-quality coins remained in circulation, but it was not enough. Hunger and unrest resulted.