Chapter 11 (Part 2): Balance Sheets of Brutality: Debt and the Business of Colonial Terror

Western Europe lucked out by discovering the Americas—Graeber argues that debt resulted in untold tragedy and terror that befell over 70 million lives

If you are new here, we are reading David Graeber’s Debt: The First 5,000 Years. Catch up and join us on Thursdays in 2025. My first slow read here on Substack in 2023 was David Graeber’s The Dawn of Everything. These two books showcase his thesis on the development of humanity by looking at how people organise themselves and their world around human values and choices. Unique among his peers, Graeber still asks the big questions in anthropology.

Hi Reader,

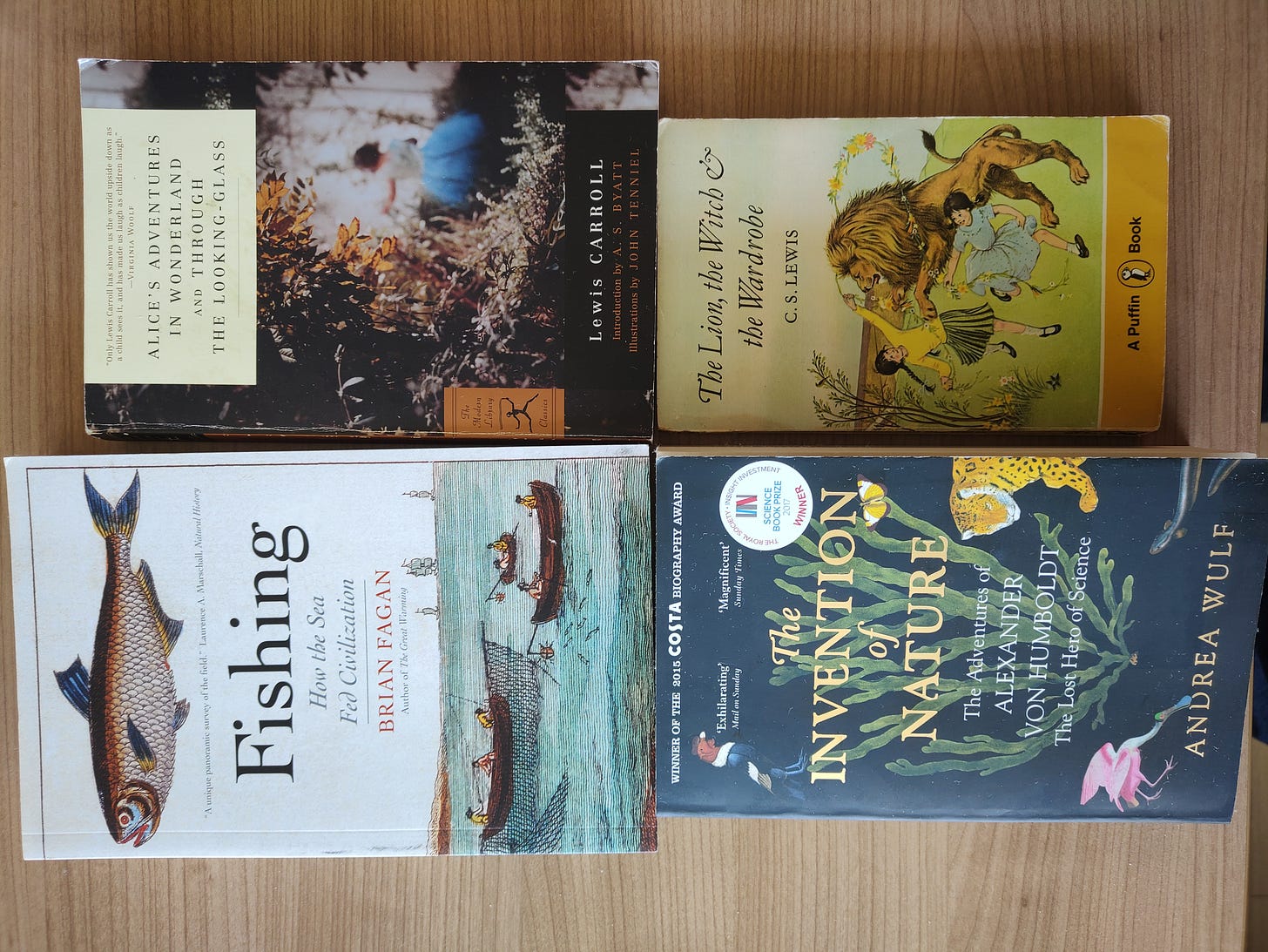

Since I follow so many classical education and Great Books blogs, I have been motivated to check out some easy classics—stuff that you know but never read in the original. I thought this was the best entry to get my brain prepped for a different way of writing, thinking, and storytelling. Here’s my last weekend haul from a second-hand (now favourite) bookseller (nothing rivals the bookstores in the UK and the USA) but there are some random gems atop all the Pattersons.

The children’s books offered original pen illustrations and a great affordable starting point. I never liked the story of Alice in all its media reincarnations but it might just be because I never read the original story—the same goes for C.S. Lewis’ work. Let’s see if these change my mind. I doubted buying the popular paperback that yellows so quickly and has a spine that will break soon (very annoying), but I wanted to read about Humboldt on my next trip. So let’s see how it goes. The winner, of course, is the Yale Press book on fishing in history. Printed on acid-free paper and with a sewn spine, I cannot ask for more, this is the best of all worlds. I hope to discover more. I have my eye on a handy Oxford English dictionary and I think I should return to reading words and discovering succinct terms—just like how I learned when I was young.

Also, one household offered free branches on the road for Easter decorations. I was cycling and found it!

Thanks, kind neighbour! This might be a Dutch cultural detail and I may have misunderstood this as a Palm Sunday frond. I will report again next week if they will use this in church or the procession.

Onward,

Melanie

It is tempting to declare that violence is an inevitable business innovation. This is the logical conclusion following last week’s post. Last week, I deep-dived into a compelling argument put forward by Andre Gunder Frank explaining the misplaced thesis that the West had the advantage. Rather, he showed that the inflation in the West, and its absence in the East demonstrated the power and dynamism of the Asian economy.

It is a compelling story explaining how Western Europe was a peripheral player in the most valued trading region in the world—Asia. Granted, if we follow this proposition, the discovery of gold and silver in the Americas was a boon to European prospects of buying their way into the Asian trade. And they did. The curious effect was the price revolution.

If we take this view, it becomes logical to argue that violent hypercapitalism was the next step. Curiously, that was what happened in the Americas. It is highly convincing but still lacking. This is where Graeber and I agreed.

surely, we were not all driven to purely economic means, homo economicus

was hypercapitalist violence and terror in the Americas truly the inevitable outcome of money scarcity?

Graeber even questions whether we can use a modern understanding of the balance sheet to explain the past

Graeber asks, if conquest was merely an economic exercise, why did China and India avoid the same path? Gunder Frank would say, they were already wealthy and had no economic incentive to do so. I suspect cultural and religious reasons but Graeber proposed a daring idea—debt triggered violence.

Debt, Shame and the Systematic Terror of Violence

There’s definitely something more to this than a purely economic exercise of the balance sheet. For Graeber, the systematic terrorising in the Americas is not a conceptual but a moral problem. He argues that shame and the moral obligation of paying one’s debts created a system where violence became not just a tool, but an obligation.

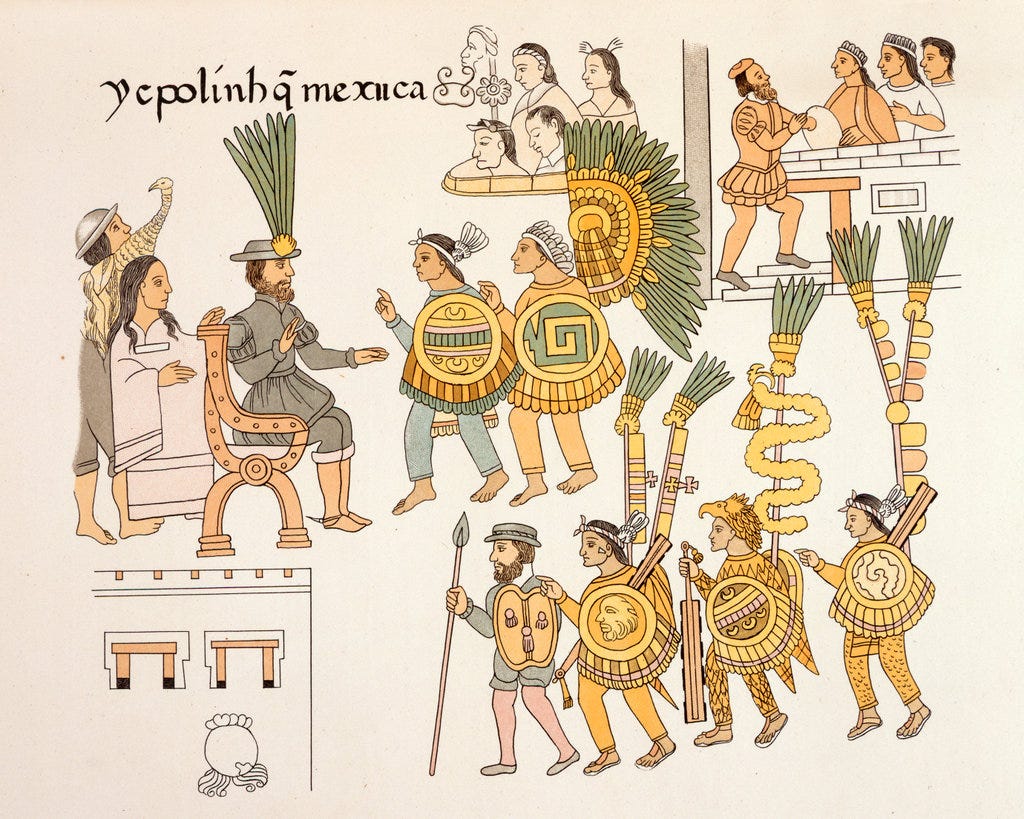

What happened in South America was harrowing and brutal. The toll on human life was deadly. If 95% of all the exports were silver, they came at the cost of decimating 95% of the population. Around the mines, Graeber states that the death rate was a hundred per cent!

The brutality of the conquistadores was staggering. Tzvetan Todorov, French-Bulgarian historian and literary philologist among other specialisations, recounted the chilling testimonies of the Spanish priests and friars horrified by the display of viciousness of Spanish soldiers. In a letter to the minister of Charles I (the future Charles V), the Dominicans reported from the Carib Island that

…When there were among the prisoners some women who had recently given birth, if the new-born babes happened to cry, they seized them by the legs and hurled them against the rocks, or flung them into the jungle so that they would be certain to die there…

p. 139, Todorov

The situation was equally dire elsewhere—in the words of Fray Toribio de Benavente (also known as Motolinia), one of the members of the Franciscans who arrived in Mexico in 1524, describes in his Historia de los indios dela Nueva España, the ten plagues that have arrived in Mexico. The fifth was the taxes and tributes exacted on the Indians.1

When the Indians had no gold left, they sold their children; when they had no children left, they had nothing more to offer but their lives: “When they were unable to do so, many died because of it, some under torture and some in cruel prisons, for the Spaniards treated them brutally and considered them less than beasts.”

p. 136-137, Todorov

These accounts of an insatiable appetite for greed and violence go on and on…

The question is, why?

The Cycle of Debt

Graeber and I agree that debt was not just a financial structure, its repercussions were weaponised. Where did this come from? Since these conquistadores were Medieval Catholics, we assume that these things would not happen. Except Graeber pinpointed that debt had a hand in this.

If we look at the figure of Hernan Cortés, Graeber disabuses us of the gallant or adventurer-conqueror that he is. Rather, he was a figure who was known as a seducer of other people’s wives when he arrived in Hispaniola, what is now the island of Haiti/Dominican Republic, in 1504. With dreams of glory, he forged on until in 1518 he managed to become a commander for an expedition to the mainland. Having acquired this command, his outlook and outward appearance shifted to one from an upper status. So says Bernal Diaz, one of his crew who accompanied him

He began to adorn himself and be more careful of his appearance than before. He wore a plume of feathers, with a medal lion and a gold chain, and a velvet cloak trimmed with loops of gold. In fact he looked like a bold and gallant Captain. However, he had no money to defray the expenses I have spoken about, for at the time he was very poor and much in debt, despite the fact that he had a good estate of Indians and was getting gold from the mines.

p. 316, Graeber

His newfound appearance and position netted him expedition loans of four thousand gold coins and another four thousand in goods secured with his estates and Indian slaves. Despite the official cancellation of his expedition by the governor, he forged ahead and eventually conquered the Aztecs and the city of Tenochtitlán.

Behind the scenes, everyone was in debt.

The division of the loot among the men netted only fifty to eighty pesos after the officers carted away most of the gold. Even more insidious, the men’s share was quickly absconded by Cortés and the other officers to pay for the equipment and medical care they received during the expedition.

We were all very deeply in debt. A crossbow was not to be purchased for less than forty or fifty pesos, a musket cost one hundred, a sword fifty, and a horse from 8oo to 1000 pesos, and above. Thus extravagantly did we have to pay for every thing!

…the only remedy that Cortés provided was to appoint two trustworthy per sons who knew the prices of goods and could value anything that we had bought on credit…but that if we had no money, our creditors must wait two years for payment.

p. 317, Graeber

Even successive Spanish merchants charged inflated prices for basic necessities to their compatriots which resulted in tensions but also a flood of complaints against the officers.

For Graeber, it made sense that these rulers of indios treated them like a paycheque.

We are not dealing with a psychology of cold, calculating greed, but of a much more complicated mix of shame and righteous indignation, and of the frantic urgency of debts that would only compound and accumulate (these were, almost certainly, interest-bearing loans), and outrage at the idea that, after all they had gone through, they should be held to owe anything to begin with.

p. 318, Graeber

Though tons of gold and silver were extracted from the Americas, none of the Spanish army and administrators kept a little of their share for long. Cortés himself never got off the hamster wheel of profit and debt. He had to petition the emperor—twice—to relieve him from a debt of five hundred ounces of gold; and second, after his expedition to California came to nought, even after pawning off his wife’s jewellery.

It seems the only people profiting were the financial creditors in Italy—not Cortés, not King Charles V—this step ladder of debt all led to the banker.

The Violence of Debt Equivalence

Graeber steers us back, not to the macroeconomics of the price revolution, but to one of the most insidious of human relations—a debt relationship. It does not seem as compelling or critical but I want to invite you back to our discussion on the creation of slave relations in Africa and how it may have happened. First, you need a conceptual symbolon of debt, such as a debt peonage system; and second, this concept was easily incorporated into the commercial markets.

If we look into the other work of Graeber, The Dawn of Humanity, we know that the Aztecs had a monarchic, autocratic and even violent type rule and peonage system in place.

The conquest of Cortés added a double violence to this system, including the transformation of all its residents into slaves. Thus, despite the admiration of the Spaniards for their Aztec counterparts, debt has erased any possible relations except slave relations. This is what Graeber has previously argued as the violence of equivalence, or when people become interchangeable with currency.

Round-Up

In my last post, I followed the hypothesis of Andre Gunder Frank to explain why Western Europe desperately needed to find a cheaper way to the East. The micro/macroeconomics of trade and the price revolution offer a convincing answer to the puzzle of why there was a scramble for silver (and gold) and why it moved eastward.

It is a compelling argument but lacking in cultural, religious (for me) impetus. Meanwhile, for Graeber, the concept of debt was a stronger reason to explain the exceptional hypercapitalism—the shocking violence, terror, greed, and indifference displayed in South America. For him, shame and frustration brought about by debt relations were greater inducements for violence, not the impersonal trading balance sheet.

Graeber’s argument has a basis in the creation of the slave trade in Africa. Though it happened much later in humanity’s timeline, his concept of the violence of non-equivalence, where social relations are erased and we are left with people becoming currency, is equally compelling. Mesoamerica’s cultural basis for debt peonage existed which was easily transformed into commercial and slave relations. The Spanish conquistadors simply overturned the Mesoamerican elite creditors into slaves themselves and unleashed hell.

Sources:

Gunder Frank, Andre. 1998. ReOrient: Global Economy in the Asian Age. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Todorov, Tzvetan. 1984. The Conquest of America: The Question of the Other. New York: Harper & Row Publishers

Find your way around: the book outline

Re-read the previous post:

Chapter 11 (Part 1): The Bottomless Metal Sinks of Asia

Did Western Europe radically innovate its capitalist practices because they were economically lagging behind Asia—the economic superpower?

Todorov pp. 136-138 outlines the ten plagues that visited Mesoamerica:

smallpox and measles disease

died by arms during the conquest of New Spain

great famine where harvests of grain and corn were destroyed

mistreatment by overseers through overwork or sending them afar

great taxes and tributes

gold mines and the countless worker deaths in the mines

construction of new edifices and tearing down of old temples in Mexico using forced labour who were unfed and haunted by hunger

the trafficking of slaves

provisioning of food and supplies to the mines sometimes from long distances with no food

wanton execution of Indians as a result of warring factions among Spaniards who did this in anticipation of potential local revolts