Slow Read Book Club: Chapter 9 The Dawn of Everything by David Graeber and David Wengrow

When Mesoamerica schools us with democratic governance

Dear Reader,

Thanks for the call. By now, you know that I did not use your real name as I was not sure if you wanted me to use it. The call invigorated me. And the most exciting part was that I just read more exciting revelations about the Mesoamerican cities that astounded me. That gave me a spring in my typing fingers. I hope to even have the time to do justice to them here. I hope you are still following the posts.

Warmly,

Melanie

One of the reasons that I started this was for my friend who has dyslexia and ADD which makes it difficult for him to finish long books. There’s so much untapped knowledge here so I decided to do a slow read with him. On days like this when I read something new that changes the way I think, I hope he will get a chance to read. Just like you, fellow readers.

Mesoamerican Jump

In Chapter 7, I mentioned that much of Mesoamerican finds are informed by colonial records and verified with archaeological data. Unlike the Chinese records, some of these written records benefitted from first-hand accounts from witnesses and second-generation descendants. The points of view of the people were added to these colonial accounts which allows us to see, in a few sentences, how democratic systems were practiced when much of the early forms of writing were destroyed upon contact and during Spanish rule.

The Mesoamerican case is not typically where we would go looking for egalitarian cities. It is well known for being monarchic, autocratic, and violent. Apparently, Graeber and Wengrow found one anomaly and another unregarded information that gives us important clues to what it means to have democratic governance.

Mesoamerican Timeline

I do not even attempt to be an expert on the overlapping and multiple cities and civilisations that is Mesoamerica. From what we know, as we approach the years 1200 BC or post- Late Neolithic, we see a shift towards autocratic systems of rule. These characterise a majority of the major civilisations listed below. Graeber and Wengrow focus on Teotihuacán a city famously known for its ritual killing atop its pyramid and deadly ball games. What it is not famous for is a revolutionary change that reversed this system. The time frame is 1 AD much later than what we have been exploring.

The other city is Tlaxcallan1, one of the highland cities in the Puebla Valley (see map below). It offers us a glimpse of how decision-making occurred prior to the subjugation of the Aztec Empire by Hernán Cortés and Aztecan rivals. It is both an astonishing story and one of deep sadness of loss that marks the colonial erasure of culture and language.

Teotihuacán

The temple city is located about 50 kilometers from modern-day Mexico City.

The most prominent feature of this city is the three pyramids: the Pyramid of the Sun, the Pyramid of the Moon, and the Feathered Serpent Pyramid. However, Graeber and Wengrow surprisingly separate the urban growth with pyramid construction. Or at least that the residents are contemporaneous with the pyramids.

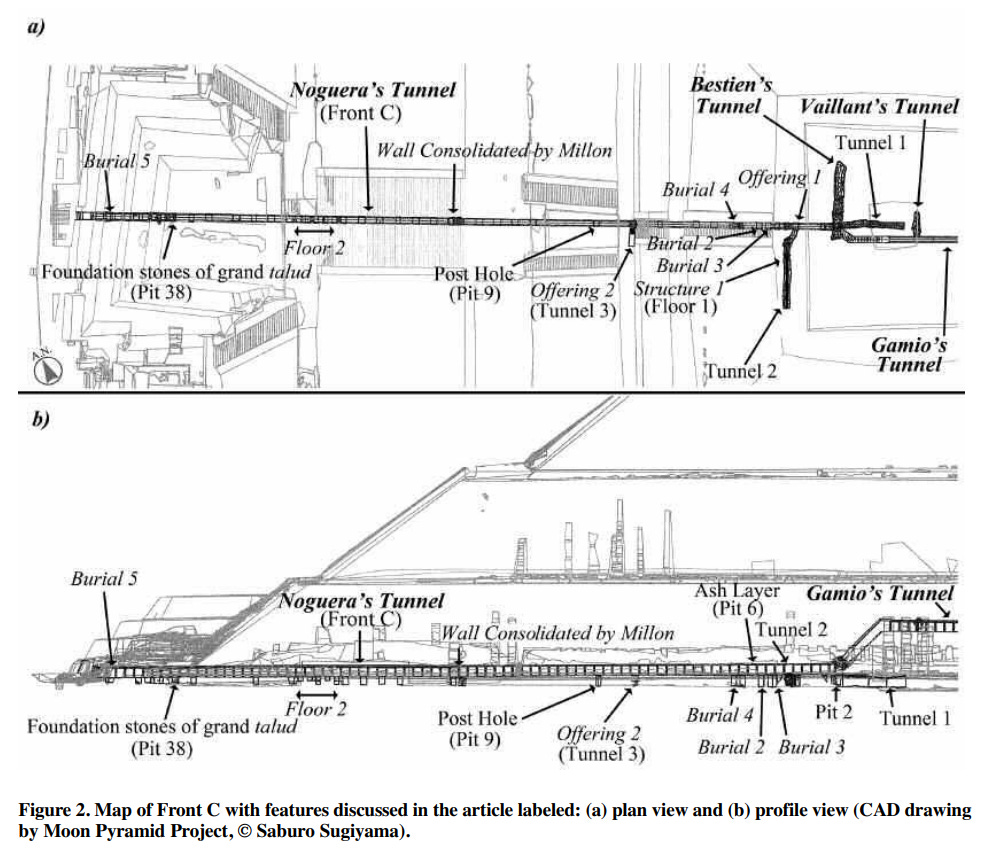

The dates of the construction of the pyramids are contentious. I follow the summary and conclusions by Maria Torras Freixa (2018). Archaeologists argue that the pyramid was constructed around 50 - 250 AD (Sload 2017) or 200 - 250 AD (Sugiyama 2018). The dispute lay around the different ways the site was dated. These would range from carbon 14 remains to ceramics, to the samples found in the tunnels and caves underneath the pyramids. The difference in dates affects how we understand the site itself.

Freixa creates a picture for us. During the early phase (1-150 BC), Teotihuacan was populated by emigrations from neighbouring settlements like Cuicuilco or Tetimpa either from the eruption of Popocatepetl or religious reasons. During this stage, it is clear that the settlement is organised in a kind of sacred grid pattern. We know this because the pyramids were built atop small structures/caverns and linked to each other or to plazas using tunnels that pre-date the pyramid construction. However, the stone residences came much later. We don’t fully know what the houses looked like then. Graeber and Wengrow postulate that they may be of wood or look like shanties. What is clear is that the religious symbolism is strongly linked to the buildings and cavern system and the identity of the residents.

By the time of 200 - 250 AD, large building projects commenced and were carried out during a short period of time for the three pyramids. The location remained consistent with the early periods such as the buildings found on those sites as well as maintaining the Avenue of the Dead. In an estimate by Murakami (Freixa 2017: 234), he estimated that it would take:

Five-hour work days for procurement and transportation

Eight-hour work days for manufacture and assembly

Using 30, 60, and 100 days per year devoted to construction

He came up with the estimate that it would take 10 years to build the pyramids one after the other (Sun, the Moon, and finally the Feathered Serpent) with 1 person for every household with 5 members (or about 35,000 people (60 days) or 21,000 people (100 days) per year). Like other Late Neolithic monumental sites that we have covered, there is no archaeological evidence of how this was done or who would have instigated it. It is unclear if there really was an autocratic ruler or if the rulers were priests and priestesses who operated the city functions using the 260-day ritual calendar, the 365-day solar calendar, and the 584-day Venus cycles. What we do know is that ritual killings were necessary in the process of construction with human sacrifices found in the Pyramid of the Moon.

During 250-350 AD, there was what Murakami (2019) calls an urban regeneration project that occurred in Teotihuacan with the building of 2,000 apartment compounds for its estimated 100,000 residents. Unlike in the early phase of the city, this time the apartments used lime plaster made locally and imported andesitic cut stone from a non-local quarry.

It is unclear who instigated or funded this but Murakami suggests a communal or neighbourhood exchange provided the labour for its construction. Again, we see here a bottom-up approach to urban design with large apartment blocks that can house 100 people with shared common ritual altars or pyramid-shaped altars.

The likelihood of these neighbourhood councils and assemblies (early barrio parish system) as a form of governance makes it plausible to see that no autocratic ruler or centralised bureaucracy is necessary to run the settlement.

The decline of Teotihuacan is unclear but during and after 550 AD it was most likely due to a combination of economic, political, religious, and social. It culminated in the cataclysmic destruction of the Teotihuacan city centre and all its temples by 650 AD. Millon (1988) describes it as an iconoclastic fury of Teotihuacan residents against itself. There was untold pillaging, destruction, and selected burning of temple walls, statues, bricks, and political centres for unclear reasons.

Tlaxcalle (Tlaxcala)

This is one of the numerous cities located in the Puebla Valley at the southern tip of the Central Mexican plateau that includes Cholula famous for its pyramid. It is now in the modern-day state of Puebla, Mexico.

The reason this city was selected by Graeber and Wengrow was for three reasons:

The city is one that has a democratic form of governance that includes political collective decision-making

Though it may have a rank social hierarchy, it does not fully have control over others.

The city played a role in the conquest of Tenochtitlan by using Hernan Cortes to defeat the Aztec Empire

Interestingly, this socio-political and cultural identity was strong enough to resist incorporation into the Aztecs despite being surrounded and fending off regular incursions.

The ancient city is located only about a kilometer outside of the modern city today. It was only settled in the hilltops and hillsides between the period of 1250 - 1519 AD. It grew from 22,500 - 48,000 people in an area of only 4.5 square kilometer producing a dense 50 - 107 people per hectare. Its public architecture only cover 3 square kilometers. The city is notable in the Mesoamerican cases for the absence of:

large scale palace-like structure on top of platforms

no large house greater than 1000 square meters

no pyramids even though they would have known about the pyramids in the neighbouring cities of Cholula, Teotihuacan, and Tenochtitlan

It appears that Tlaxcaltecas were defining themselves opposite of those cities. Instead, they have 24 multiple small plazas scattered and surrounded by residential terraces in which there were roads that passed between terraces for public acces.

Governance. No central plaza characterise the urban Tlaxcalle. It has 20 neighbourhoods that Lane Fargher et al (2011) call the tlaca represented by its own official teuctli. These neighbourhood units are the smaller administrative scale units of the teccalli “state” of Tlaxcalle. The absence of a palace or a central plaza containing residences and offices of the rulers meant that Tlaxcalle governance is highly decentralised and open. Ethnohistoric data show that between 50 to 200 officials teteuctin governed Tlaxcallan. Fargher calls this an ancient republic.

The way that they debated, negotiated, and convinced their fellow citizenry whether to build or possibly kill the party of Hernan Cortes deserves its own addendum post! It was just so good. Suffice it to say that, for good or for bad, the Tlaxcaltecas reasoned a strategy that also led to their demise — a prophetic warning voiced by others.

Round Up

What we see here are exceptions to the Mesoamerican rule — a few egalitarian strongholds in a time where governance meant autocratic rule. We have learned that:

autocracy and democracy seem to operate in a cycle (destruction and rebirth) when the social, environmental, religious, and political limits are reached

though rare, it seems that there is a deliberate choice to identify against the norm, in this case, autocratic rule by separating from the city into the hills and enforcing a decentralised form of governance

we see both forms of autocracy and democracy as necessary two sides of the human condition — always an option open for people

We can ask ourselves, what options do we still have now that we reached “state” developmental level.

Tlaxcalle (Nahuatl) and Tlaxcallan (Hispanised spelling) are pre-conquest terms for the ancient city. After Spanish conquest, the spelling Tlaxcala was used. Following, Lane Fargher’s use, I am using the pre-conquest term for the ancient city.