Slow Read Book Club: Chapter 7, The Dawn of Everything by David Graeber and David Wengrow

The search for the origins of monarchy in the Neolithic period continues...

Dear Reader,

Chapter 7 continues with the story of plant domestication, agriculture, and urban cities. Somewhere in these larger-than-life questions lies the true interest of the authors to investigate how and why people rejected central authority. I was not feeling too confident that the two David’s were anywhere close (see last post) to answering their question. I don’t think this chapter or the succeeding ones will be closer but it is good to see the supporting evidence for a strong speculation. Let’s jump right in.

Melanie

Catch-up

While the authors might be frustrated over the limits of the archaeological evidence to support their perspective, there are promising indicators of what forms of social organisations are in egalitarian societies.

Neolithic non-hierarchal societies tend to have more female-oriented figures in their symbolic art. They also have a mixed economy of foraging, animal husbandry, and slow farming.

Neolithic hierarchical societies tend to have more male-oriented symbolic figures with an emerging emphasis on hunting or warrior-based activities. It is notable that female-oriented art disappeared from the archaeological record in these groups. However, these groups maintain a mixed economy of foraging, cereal production, and consumption like their counterparts.

The surprising fact is that both these arrangements co-exist simultaneously. The options are open for people to create their own settlements and co-exist with other groups of people.

Therefore, it is important to consider the different forms of social arrangements that emerge from political choices, despite similar access to large-scale urbanisation, cereal cultivation, and consumption.

There is simply no reason to assume that the adoption of agriculture in more remote periods also meant the inception of private land ownership, territoriality, or an irreversible departure from forager egalitarianism.

In fact, we see the reverse. Large settlements with some form of cereal crop cultivation but with no centralised authorities or elite structures. Clearly, people knew about cereal agriculture and yet, we see different cultures that refused to adopt them.

The cultural refusal of agriculture

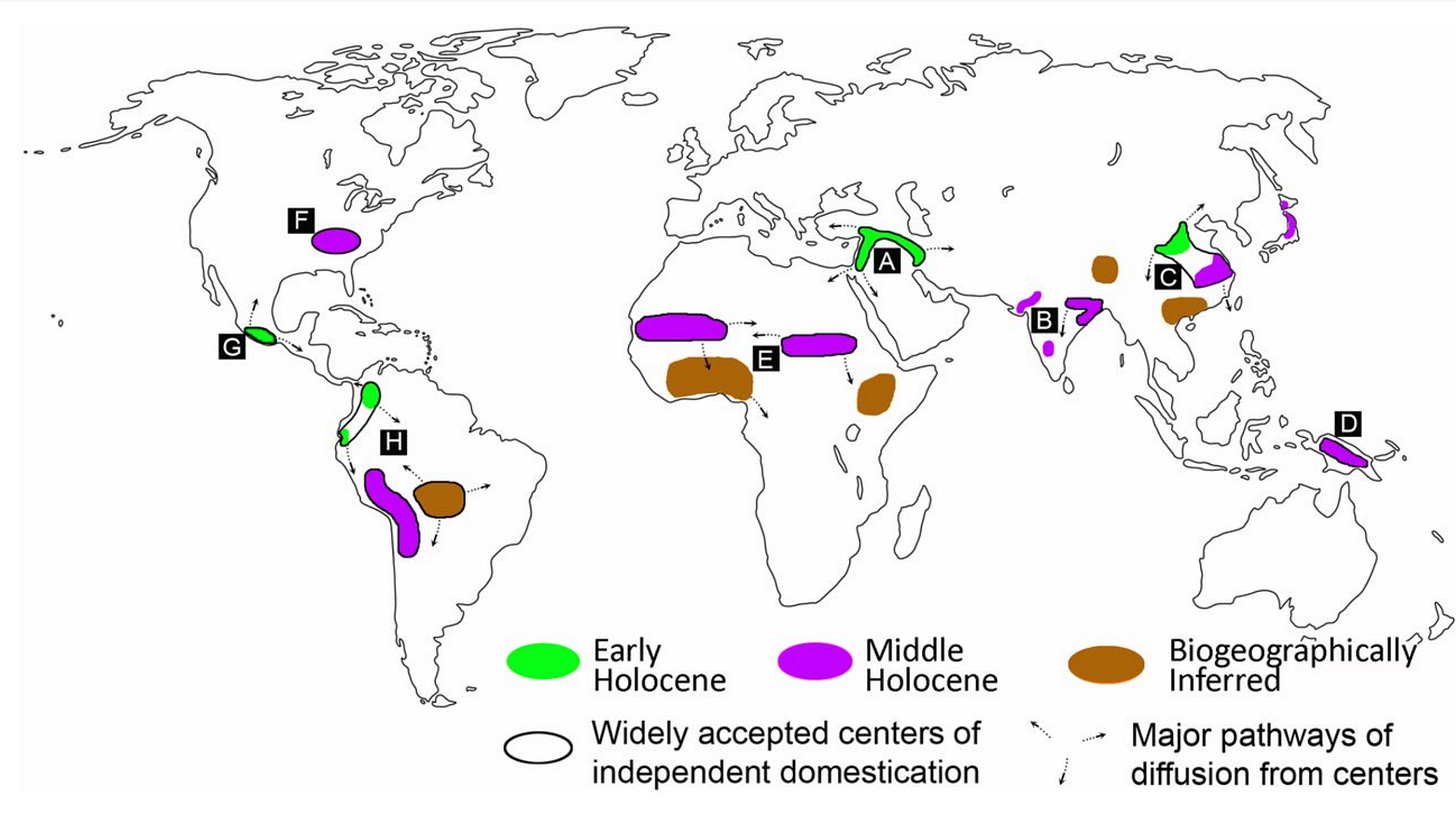

There are fifteen to twenty independent centres of domestication with varying social arrangements. The authors’ question is: for 200,000 years, why didn’t farming develop much earlier?

According to Graeber and Wengrow, there were only two sustained periods of warm climate that could have left archaeological evidence of an agricultural economy. One is the current epoch we are living in which began around 12,000 years ago. The second was the Eemian interglacial around 130,000. Imagine the hippos on the banks of the Thames and the Rhine!

This golden period for foragers was also the time for plant cultivation. Riverine and lake environments provided both watering fowl and an abundance of shellfish resources like those in Çatalhöyük. A combination of environmental transformation from tundra to scrub and the cultivation of fruit and nut woodlands would bring about the extinction of megafaunas by 8,000 BC. The growth of forests meant that people were hunting smaller game like deer and elk.

This broad range of food sources is what Murray Bokchin calls the ecology of freedom wherein farming is one of many activities that people can move in and out of. It is not a permanent state of being or doing.

The failure of agriculture

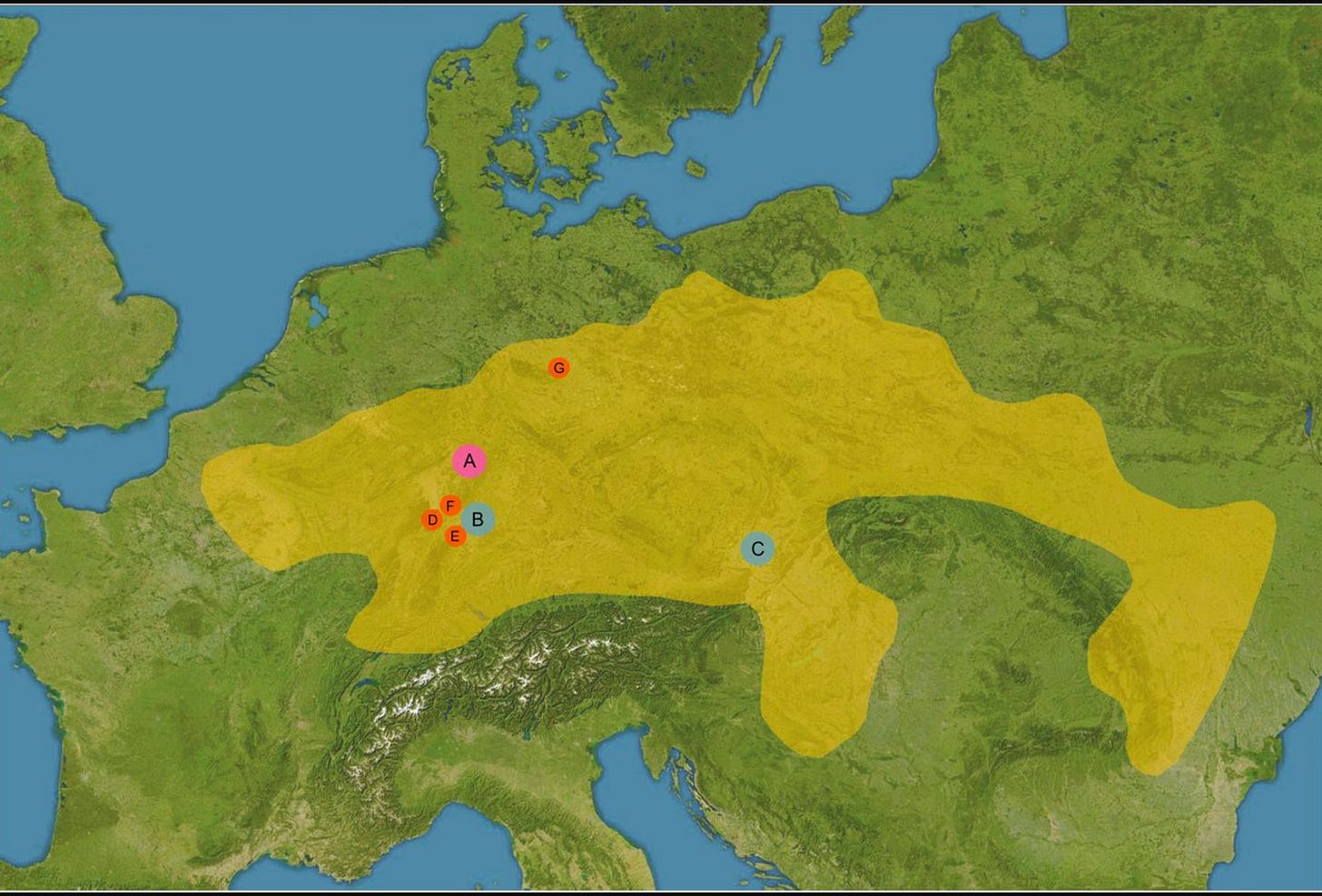

The cases of Kilianstädten (5,207 – 4,849 BC), Talheim (5,000 cal BC), in Germany, and Asparn/Schletz (5,260 - 5,000 cal BC) in Austria are some of the confirmed genocidal massacres in Neolithic farming communities.

The communities are said to originate from Southwest Asia and lived in timber longhouses in a fairly non-differentiated system. They brought with them knowledge about cereal cultivation and cattle. However, between 7,000 BC - 5,000 BC, these settled and fortified communities experienced unknown stressors that led to massacres.1

We know that it was a massacre or genocide because the 26 individuals dumped in a mass grave exhibited blunt force trauma and arrowhead injuries in Schöneck-Kilianstädten. Even worse, long bones were systematically broken and peri-mortem fractures indicated torture or mutilation while still alive. In the settlements of Talheim and Schletz, the story is grim. The entire village was massacred and dumped in graves. A total of 34 men, women, and children were killed in Talheim in a takeover bid. At Asparn/Schletz, 67 individuals were found dumped in the outer ditches of the settlement. Thirty-three of the male and female skulls exhibited fractures at the cranial base, facial bones, and mandibles. No further evidence of occupation or settlement happened in this area after this event. One interesting geoclimatic crisis could be a stressor in the region around this time - the flooding of the Black Sea (5,600 BC) that submerged about 100,000 square kilometers of fertile land.

It is interesting that problems were also happening in Southwest Asia at about the same period (6,700 - 6,500 cal. BC). Çatalhöyük was at its population peak with diseases, violence, and environmental problems. Clark Larsen estimates that about 3,500 to 8,000 individuals were living there prior to population reduction, dispersal, and abandonment. Ian Hodder gives a deeper analyses of the increasing pressure on social and physical labour as residents were balancing individual house specialisation with community dependence gift exchanges.

Long settlement practices reveal several things:

Rather than the aggressors, settlers may be prone to attacks from hunter-foragers.

Cereal cultivation and animal husbandry provide food predictability that enable longer settlement which in turn, contribute to the rise of the population and other problems in health and internal violence.

Dispersal is part of the solution to internal strife in settlements.

Intensive cultivation is a safety blanket to reduced foraging resources. This means that people could move to more hostile environments away from richer locations favoured by hunter-foragers.

Neolithic populations experience what Graeber and Wengrow call as the boom and bust cycle and a regional collapse. The problems are eerily familiar and similar to our current conditions.

The success of agriculture

Despite the threats and setbacks, the skills and knowledge of plant cultivation and animal husbandry would prove successful in other areas.

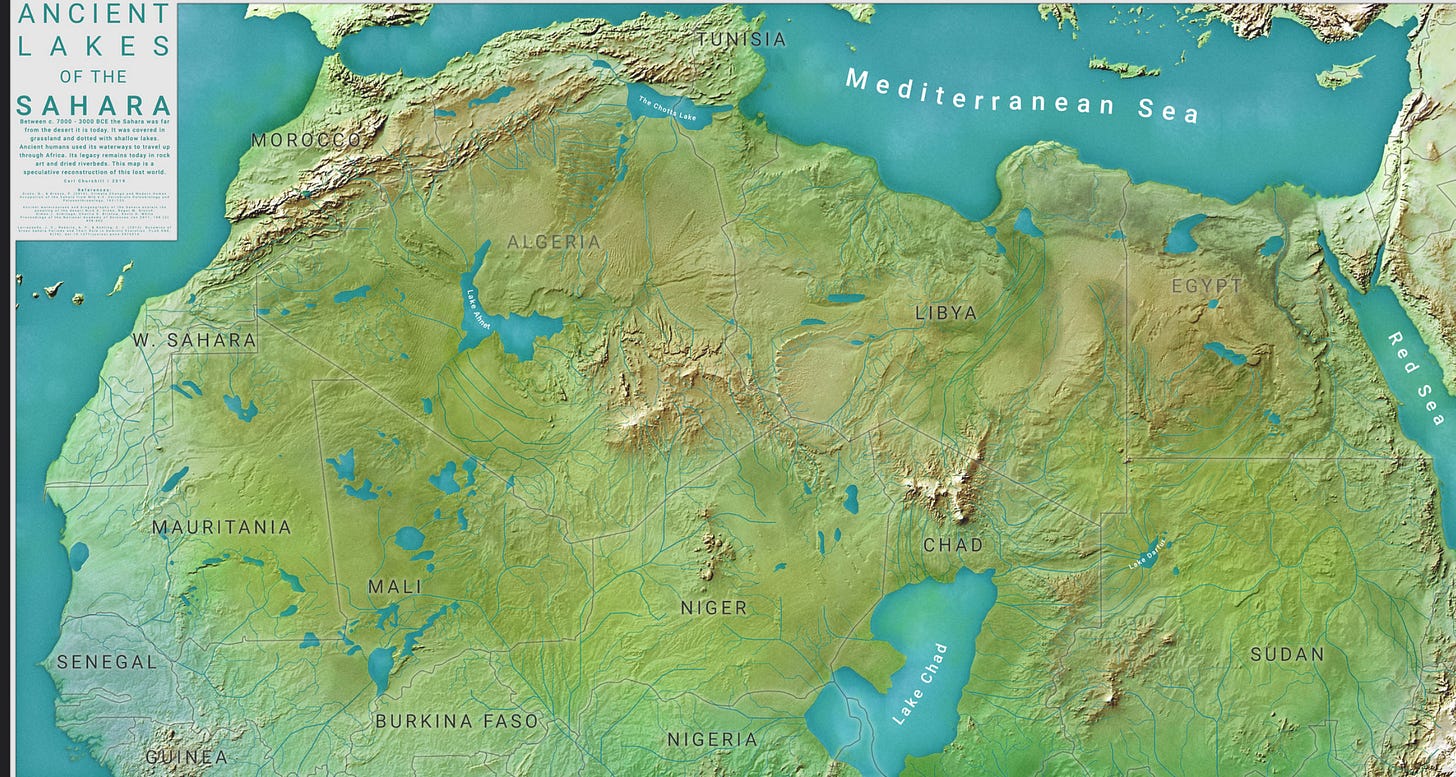

Neolithic Africa has approached this knowledge set by focusing on animal husbandry and livestock herding. Africa received more rainfall dubbing this period as the African Humid Period lasting between 12,650 BC - 3,050 BC. Sahara was green. The ‘primary pastoral community’ ditched cereal cultivation and, instead, relied on the mobile storage value from herds and fishing and foraging in the lakes and rivers.

Once the rainfall moved southwards and the plains slowly dried out between 4,050 BC until 2,050 BC, the pastoralists intensified their domestic herd strategies (enshrined in the increased symbolic importance of these herds) and moved to reliable water sources such as the Nile Valley. Once there, the seasonal movements would gradually lead to the adoption of prolonged settlement and cereal cultivation.

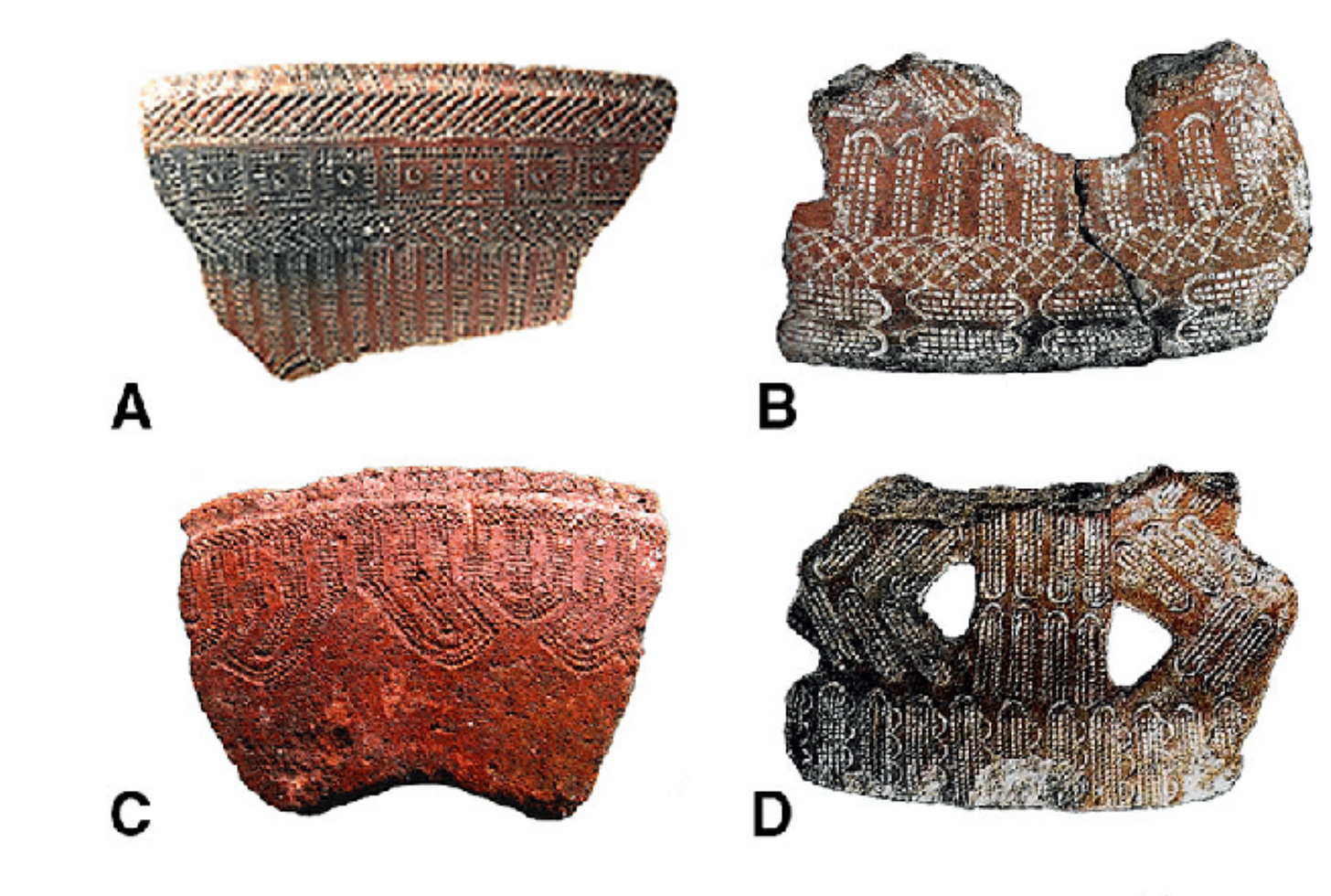

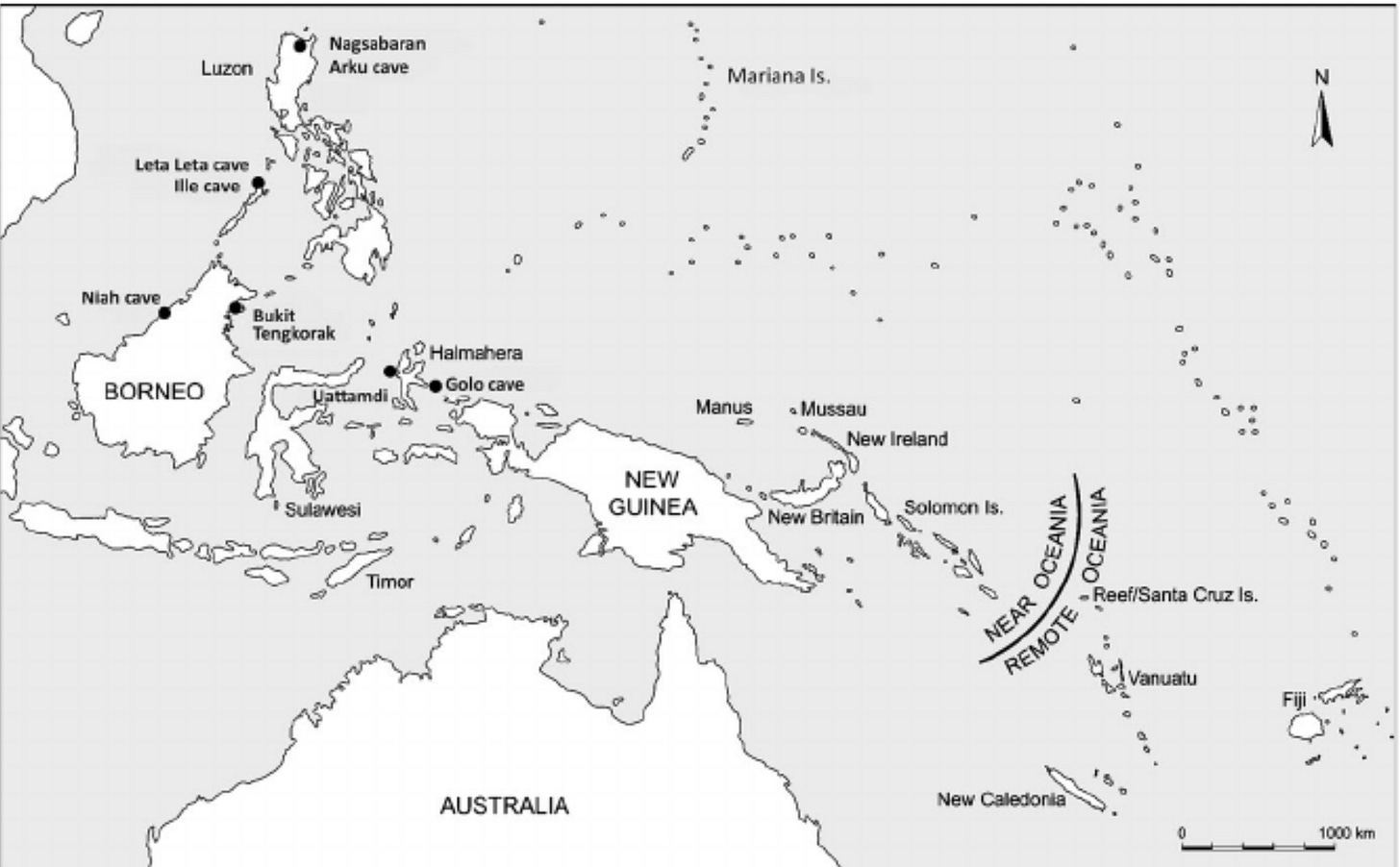

Another Neolithic tradition in the Oceanic region is called the Lapita culture (1,520 cal BC - 1,300 BC) defined by the dentate stamping pottery style that has been found from as far as the Philippines to its easternmost extension in Polynesia.2

The pottery finds have been found in Island Southeast Asia all the way to Polynesia.

Aside from pottery, the other Neolithic culture suite includes:

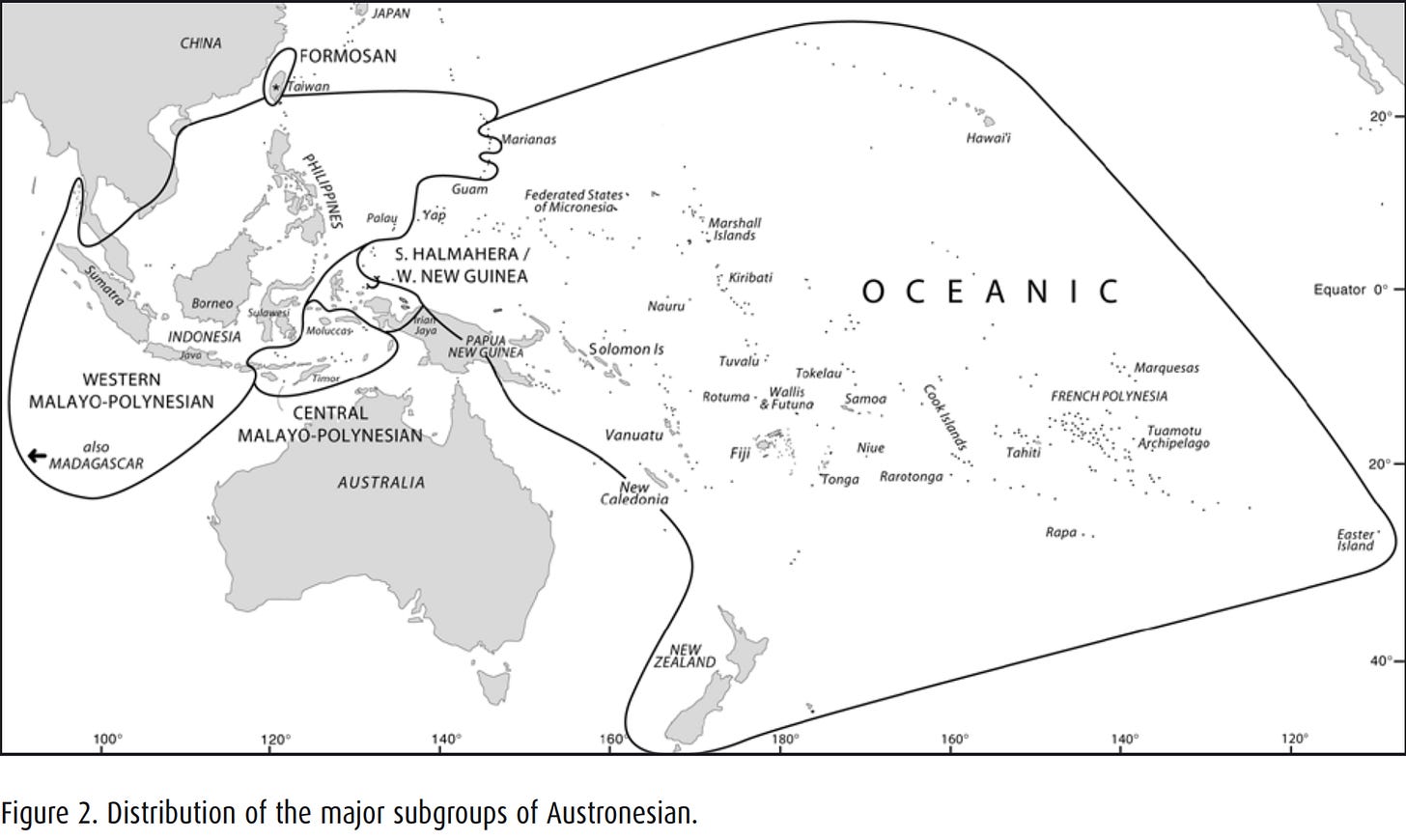

a shared ancestry of languages (Austronesian languages)

a host of animal domesticates such as pigs, chickens, and dogs.

the preference for taro, yam, and other tubers instead of rice

One hypothesis of a rice-eating origin comes from a north-to-southward movement from China and Taiwan to Island Southeast Asia (Out of Taiwan - disputed). However, as people moved eastward, rice was rejected in favour of tubers. Archaeologists have generally accepted the Triple I model of intrusion, innovation, and integration to explain why certain features seem to come from Island Southeast Asia but also explain local independent ‘invention’ of plant domestication.

In the present period, what we see develop in the Melanesian region is horticulture, or the slash and burn of forests to plant tubers and return them back to fallow.

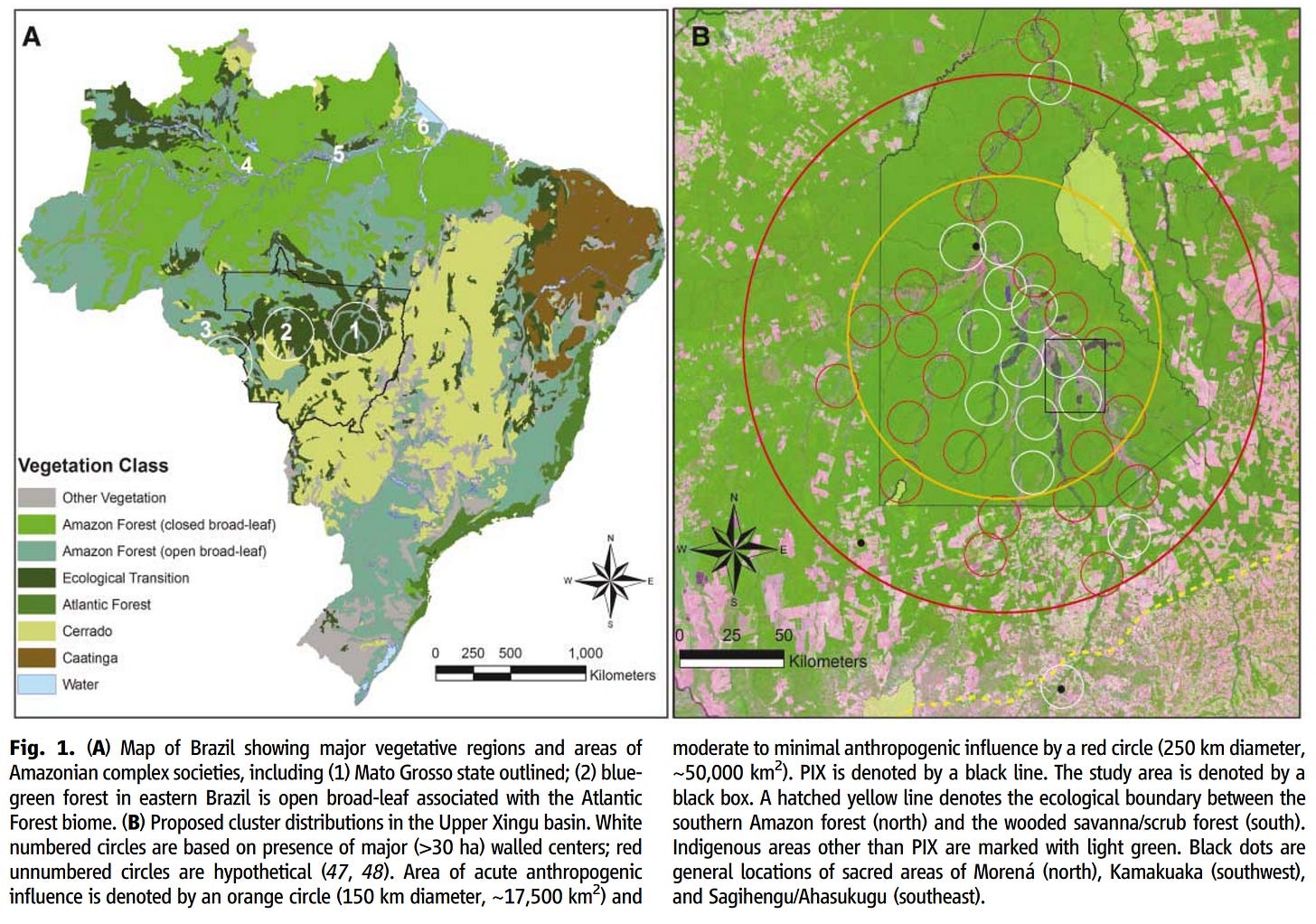

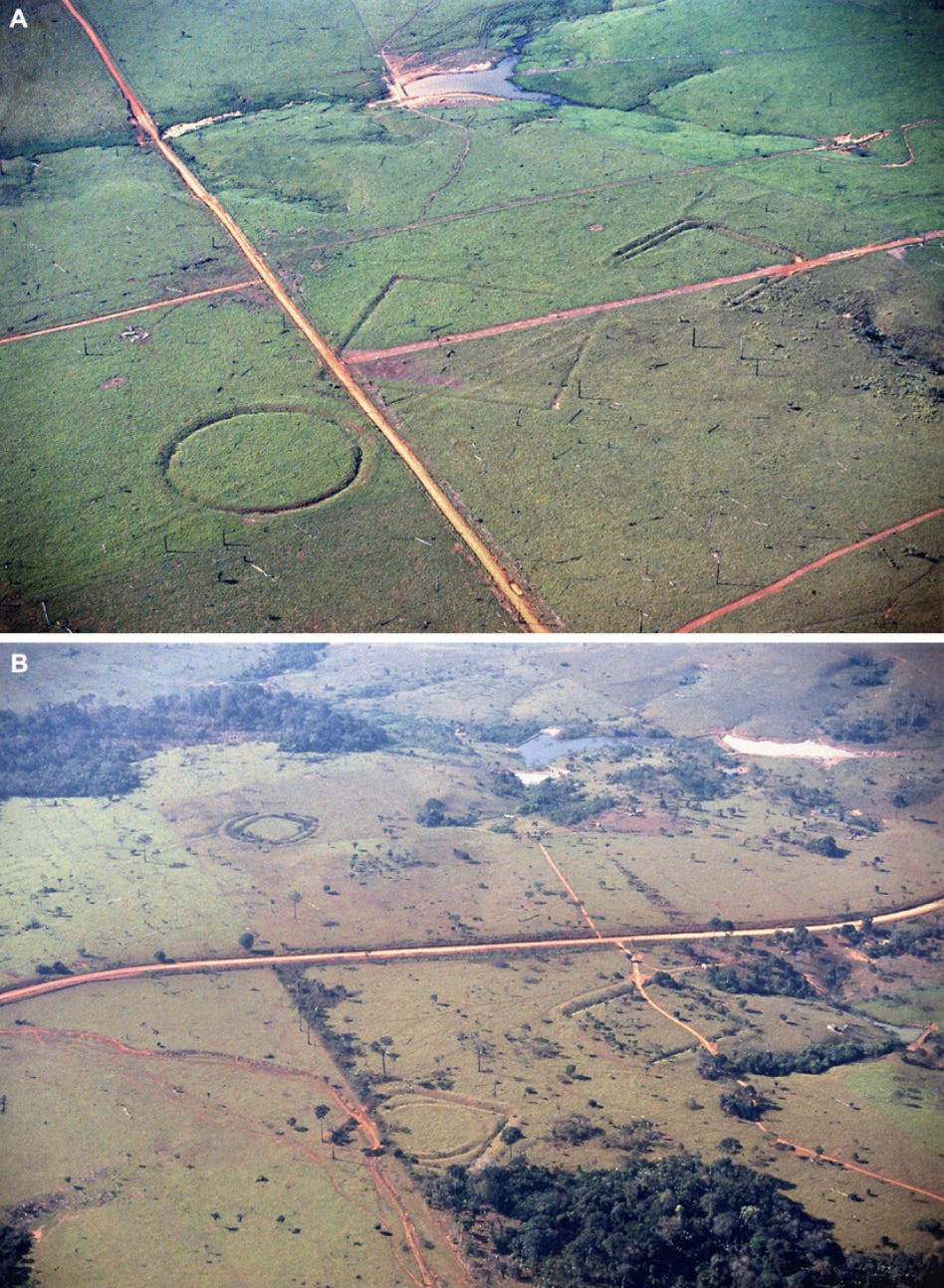

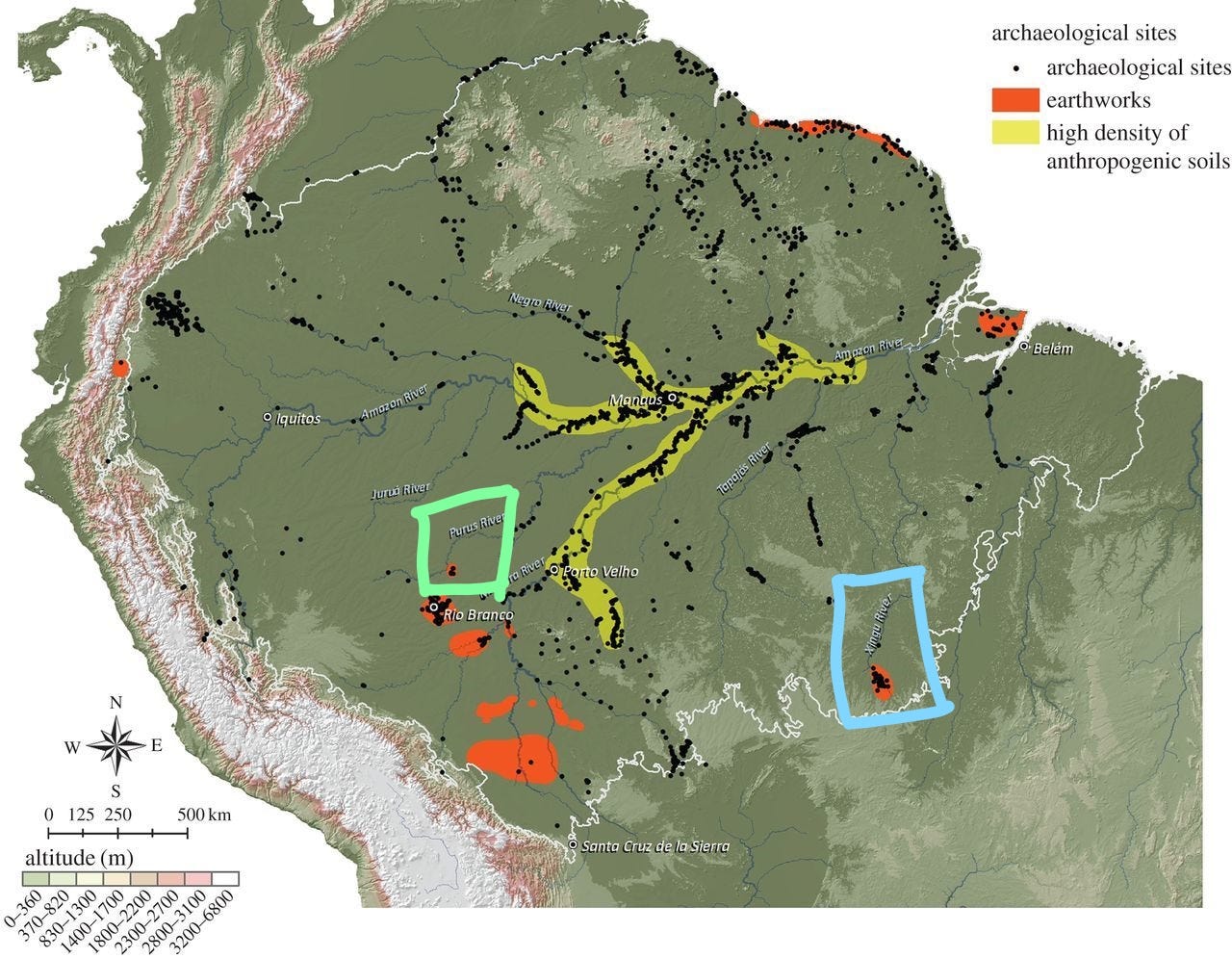

In Amazonia, the transition from foraging to intensive farming occurred around 2,050 BC. This is the garden-forest continuum according to Glenn H. Shepard, Jr. et al. (2020). This in-and-out farming consists of cultivating home gardens, swidden plots, managing forests, and use of semi-domesticated crops and wild varieties. This allows people to cultivate but also let the gardens lie fallow. However, the intensification of farming in the region coincides with the unique ‘galactic’ urban landscape along the Xingu River in the Mato Grosso region (450 AD - 750 AD).3

The settlements vary from large multi-centric plaza towns between 20 - 50 hectares in size or smaller villages of 10 hectares. They have a common pattern of a central plaza for ritual and cemetery purposes, gates, roads, and walls. These forest urban centres (1,050 BC - 950 AD) are found throughout the region such as in the Acre state of Brazil and used for at least 200 - 500 years. Remains of maize, squash, and palms were found as well as some medicinal plants and edible palms in the vicinity which are still in use.

Once we zoom out of these local places, we can see that these settlement patterns with mixed agri-forest use (including elevated farming beds) can be found throughout the region from the French Guyana coast to Brazil.

It is estimated that there would be 4 - 5 million residents that could be supported in the region. Charles Clement (1999) documented about 138 crops cultivated in the forest that would be lost once colonisation set in 1492.

Round-up

As we move out of the upper crescent of Neolithic Southwest Asia, the shape of how we recognise farming and agriculture shifts. From the Neolithic ‘package’ of plants and animal domestication, people have chosen to enact this in a multitude of ways in various environments.

The combined climactic and social pressure in Neolithic Southwest Asia and Central Europe (7,000 BC - 5,000 BC) led to massacres among farmer communities for the latter and dispersal in the former.

Neolithic Africa chose to concentrate on herding until their move to the Nile Valley which intensified into animal husbandry. These once-seasonal settlements would be the precursor to the intensive cereal cultivators around 3,000 BC.

In more humid and tropical regions, archaeological data must be combined with historical linguistics, and genetic data to put together a picture of Neolithic Southeast Asia and Oceania (1,500 BC). Evidence is still scarce but we see combined borrowing, rejection (rice cultivation) but also independent cultivation of tubers, and other domesticates in the region. Agriculture is more akin to horticulture and gardening than paddy fields.

For Amazonia, much of what we know comes from more recent colonial contact records. Understanding the Neolithic Amazonia requires contemporary ethnography and archaeology to reconstruct pre-contact and pre-Columbian settlements, farming, and domestication. The forest is truly not virgin or pristine but modified by Amazonian settlers prior to colonisation. This includes earthworks, farming mounds, agro-forestry, fortifications, and networked roads. Much of this data has been irretrievably lost.

It is interesting that we have not found evidence of structural violence away from Southwest Asia. It does not mean that it did not happen. However, we know of two things: people were living in non-state urban arrangements and were intensively farming alongside other activities. There did not seem to be an impetus to develop larger state or monarchic structures. People knew to keep numbers low and small scale or disperse when needed. Or in the Amazonian case, have a network of interconnected villages. There simply was no need for a permanent centralised authority and people designed their urban environments to avoid that.

The seed of what would be the turning point in humanity lies hidden within these early settlements that we have yet to uncover.

For further details, check, Rick Schulting and Linda Firbirger (eds.) 2012. Sticks, Stones, and Broken Bones: Neolithic Violence in a European Perspective. Oxford: Oxford University Press

For further details, check (free to download): Stuart Bedford and Matthew Spriggs (eds.) 2019. Debating Lapita: Distribution, Chronology, Society, and Subsistence. Canberra: ANU Press.

Unfortunately, most of this evidence comes after European colonisation or from contact records. Amazonian archaeology remains unique as it combines contemporary ethnographic accounts to ‘recover’ and understand these settlements.