Chapter 10 (Part 8): Credit/Debt Relations Among the Peasantry, Aristocrats and the Church

Church canon law does not reflect what is happening in the rural medieval villages or clerical activities

If you are new here, we are reading David Graeber’s Debt: The First 5,000 Years. Catch up and join us on Thursdays in 2025. My first slow read here on Substack in 2023 was David Graeber’s The Dawn of Everything. These two books showcase his thesis on the development of humanity by looking at how debt evolved and how people organised themselves and their world. Unique among his peers, Graeber still asks the big questions in anthropology.

Despite the ecumenical homilies of the early Church, it continues to struggle with the loopholes in issues of usury, profit, and interest. We proceed from p. 289 (in my PDF copy) where Graeber points out that it was not only the Jews who were the moneylenders but the Lombards of Northern Italy and the Cahorsins from the French town of Cahors. Rural usury is for him the indication of free peasantry, commercial farming and what would be the ‘commercial revolution’ in the High Middle Ages.

We shall take a look at how on the ground credit and debt transactions occur in the medieval period in Western Europe.

Periodisation

We move back and forth between the Early Medieval Period and the High Medieval Period or the High Middle Ages in Europe (c. AD 1000 - 1300). This is the demand of the existing historical records available on the rural debt and credit conditions.

We have touched upon the story of the Jewish experience in England that covered this period. However, as noted by Chris Wickham rural societies are vastly different from each other depending on region, aristocrat class, and the independence of its peasantry among other characteristics. Use this post to complement Graeber’s brief notes on Church canon law on usury and credit with how people have practiced these.

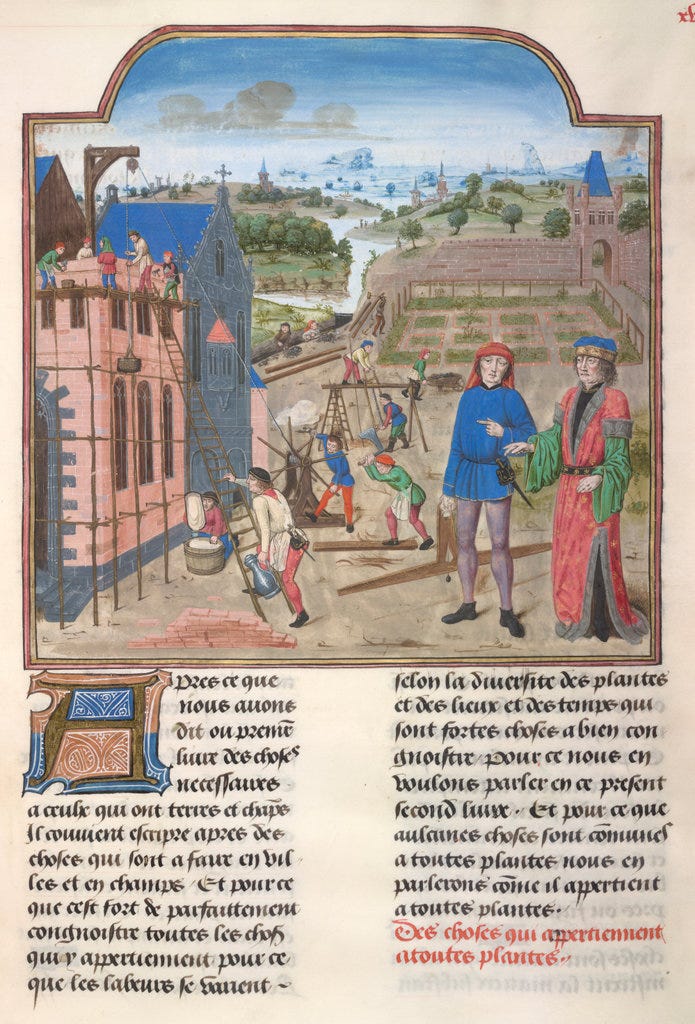

Commercial Revolution

The ‘commercial revolution’ is an approach in medieval historiography that attempts to periodise the economic history from medieval to modern capitalism in medieval Europe. I am less concerned with this as much as I want to highlight the key characteristic of this period

growth of trade, craft guilds, commercial farming and therefore financial arrangements and instruments

rise of the first centres of learning or universities in Bologna (a region controlled by the Lombards) and Paris (a tiny principality in the Ille de France) that consisted of the Greek and Roman classical training consisting of the trivium (grammar, logic, rhetoric) and quadrivium (arithmetic, geometry, music, astronomy) which became training centres of Roman law and philosophy separate from Church canon law

demographic growth, contraction, and access to land ownership

This parallels what we have seen in medieval India and Islam regions where merchant capitalism took off alongside the growth of organised religions. In medieval Europe this took the joint and separated pathways of the sacred and secular. The rediscovery of Roman law (translations from Greek and Arabic sources) provided a conceptual, legal, and religious frameworks on property ownership and financial transactions.

I want to look at the on the ground instances of interest-bearing credit, loans, and landownership to contrast to Church canon law. We see two spheres of relatively separate credit and debt relationships defined by income and class.

Sphere 1: Rural Village Credit Life

It is not easy to get a general picture of continental European rural societies because of historical and geographic particularities, says Chris Wickam. However, he poses some general criteria to look for

what is the exclusive rights to landownership

what is the strength and permanence of ties of dependence

what is the extent of inherited or acquired status and authority

The answers vary but what he describes usually fall into two loose groups

an aristocratic or kingship group (who may also be landowners)

peasant cultivators who may be free or dependent (in varying forms or intensity)

As an example, Wickham describes ninth century Brittany from the charters1 found in the monastery of Redon. Here, Brittany had two groups. Machtierns are aristocrat landowners with civil responsibilities. However, they have little coercive power over the plebenses or villagers who are the cultivators but also ran the business of courts. There is a supra ‘national’ aristocrat called principes who exerted military power and also greater control over plebeian civil matter than the machtierns. The difference between the two noble groups is that the former had a more direct relationship to the villagers than the latter. This is important in the realm of social obligations and exchange relationships (or its absence).

Horizontal Debt Relations: Within and Inter-Village Credit

Debt and credit arrangements are predominantly conducted within the same area of origin and within local networks. Thus we see records of activities among a similar status group of creditors/debtors.

The Duchy of Přemysl (Czech) in AD 1050 and 1200 show a direct credit/debt relations when it came to land. These were simply purchased and exchanged for its value because property is treated as partible commodities.

A grant to Plasy made “by hereditary right” on the part of a woman named Agnes, for example, included a village: “bought back from Drslav with my own money, which my husband Kuno had sold to him before our marriage.”

p. 20

Meanwhile in Bedfordshire, England in 1332-3, Philipp Schofield found a similar occurrence. Thirty seven out of seventy-six pleas are for debt in Bedfordshire. He cross-checked the county rolls and found that these relations are circumscribed around the same village with other areas not exceeding twenty-five miles (40.23 kilometers).

![The fifty-two Countries [sic] of England and Wales described in a pack of cards The fifty-two Countries [sic] of England and Wales described in a pack of cards](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F345c509f-9f49-4690-b403-b54d4eae3d49_647x1024.jpeg)

He found that county transactions show

fifty percent of all debt are for deferred payments of goods—animals and cereals

only twenty percent of them refer to leases to land and animals

debts seldom exceed 40 shillings

borrowing tend to be horizontal or among kin and neighbours and would not end up in the court rolls

poorest individuals were absent in the court rolls or did not seem to be engaged in any credit transactions

local gentry, clergy and wealthy landowners acted as creditors in some instances

The common security for credit was primarily for produce or harvests.

One such individual is Robert, son of Adam, from Bury St. Edmunds manor of Hinderclay (Suffolk). His recorded possession of £4 was linked to barley which was incompatible with his landholding. This meant that he was able to add his income through additional capital or a second employment elsewhere.

Sphere 2: The Aristocrats and the Church

The sphere of debt relations between those in the upper rank inevitably led to the consolidation of power of the Church. The accumulation of Church and monastery estates began in the early medieval period of the fifth and eight centuries when there was a vast transfer of land. Similar to the monasteries in medieval India, these pro anima gifts bequeathed to the church were investments for the souls of the donor(s) and their families.

These land gifts made the Church landowners. However, rather than a complete loss, the family can negotiate an agreement of in precaria or a type of lease in which the family can continue to use the land or the possibility of claiming it back at a later time. This arrangement ensured that both parties continued to benefit in the short-term (awarding of positions) and long-term (perpetual tenancy). This relationship entangled the aristocrats with Church officials and established patronage networks between them.

Land was also accumulated through smaller donations. In one obscure record by German legal historian Paul Roth, Ian Wood (p. 40) noted that St. Germain-de-Près held around 429,987 hectares in the ninth century or closer to 1 percent of France.

These lands became the dueling asset between the kings and the church leaders during the Carolingian period. Some would revert back to the families and some would remain under dual management, cementing the (contentious or cooperative) relationship between these two different power bases.

The income tended to the corporal and temporal needs of the Church as the income from these lands were used for:

feeding the monasteries (tens of thousands of clergy occupy 130 dioceses of Gaul)

support for the poor, widows and orphans which were the principal mission of the church donations at that time

supplies for manuscript production (e.g. 1,545 high quality animal skins were needed for the three Pandects of the Bible (collection and compilation of law and other documents) in one monastery at Wearmouth-Jarrow)

These horizontal debt relations within the upper strata ensured that there is enough money for it to trickle down to the lower ranks or ordinary people.

Vertical Debt Relations: Clergy and Merchants

There are better records of how this looked like in the twelfth century. In AD 1300-1349, we see better court records of the clergy becoming creditors and investors to merchants because of the tithes-produce that they received. Pamela Nightingale (p. 89-105) investigated the certificates of unpaid debt from the Statute of Acton Burnell of 1283 and found clergy registered for loans and other transactions. Interestingly, there is no record of interest ever being registered there.

There are 239 loan certificates that survived with an average value of £20. This amount was equivalent to 1,600 days wages for a skilled craftsman according to Nightingale. The clergy was identified as rector or parson who were economically well off than the vicars and chaplains. This is because chaplaincies had fixed stipend of 5m (marks). However, Nightingale proposed that more leisure time, their urban location, and perpetual grants meant that their credit line increased from £11 in AD 1300 to £22 in the 1340s.

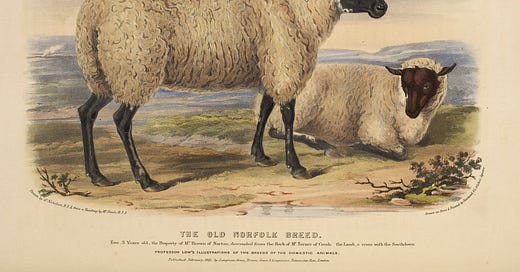

It is no accident that there was a high amount of financial activities in Norfolk. At that time, Norfolk had

a commercialised agriculture (exports of wheat, barley, wool, ale), linen, and worsted industries that created a high demand in credit

free peasants with loose kin networks thereby seeking loans from the marketplace rather than family

Connections with the Athelwalds (wool-brogger and exporter, William Athelwald of Egmere) also encouraged other parochial clergy to invest: in 1333 William Athelwald advanced £32, in partnership with the parson of Letheringsett, for four sacks of wool and £4 in cash.

p. 100

The Norfolk clergy lent lower loan amounts to more people. The income was used to acquire property in preparation for retirement and old age.

The Circumscribed Spheres of Debt Relations

These two spheres are analytical distinctions that I saw while reading about the debt relations. I initially tracked Graeber’s sources but found them behind the paywall. While reading other sources, I saw a preponderance of debt relations circumscribed along similar status groups.

This meant that credit/debt transactions occur within the group, for instance among villagers and peasant cultivators. These are mostly to fund seasonal produce and animal products. For the aristocrats and Church officials, they typically deal in immovable assets such as land. These land gifts are readily translated into power and profit when usufruct rights are awarded to the same families. These establish a patronage relationship that traffic between secular and sacred power and create incomes for both parties.

The vertical relationship between someone in the higher rank and in the lower rank predominantly involve smaller loans and in seasonal produce. I have yet to see large scale land transactions occur between those of unequal rank but see this list of researchers.

Graeber focused on the intellectual struggle of the Church on the nature of usury between pp. 289-290 (my PDF). The call to apostolic poverty especially by the mendicant orders of Franciscans and Dominicans contravene the corporal needs of churches and monasteries. It is true that land grants have become the pathway to power but it has also allowed the support of a large population of scribes and income to help the destitute.

Round-Up

Our focus in this post is on the ground credit and debt relations during the early and high medieval periods. While Graeber focused on the struggle of the Church canon law against profit or private property, I wanted to present a more tangible story on how credit relations play out in the rural areas.

What I found was two spheres of interaction circumscribed along status lines.

Peasant cultivators tend to borrow within their group and for smaller amounts to tide them over their next harvest or animal rearing.

Aristocrats and Church officials negotiate over valuable immovable assets such as land. Unlike land grants in medieval Buddhist India, these Church assets translate into secular power. Land becomes a pawn for secular leadership positions and financial power.

Both groups intersect when the upper rank become creditors within their local regions. So far, this interaction involves minimal transactions seen in court records.

Sources:

Muldrew, Craig. 2018. Afterword: Mortgages as Mediation Beween Kin and Capital. In C. Briggs and J. Zuiderduijn (eds.). Land and Credit: Mortgages in the Medieval and Early Modern European Countryside (Palgrave Studies in the History of Finance). Cham, Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 309-326

Nightingale, Pamela. 2016. The English Parochial Clergy as Investors and Creditors in the First Half of the Fourteenth Century. In P.R. Schofield and N.J. Mayhew. (eds.) Credit and Debt in Medieval England c. 1180-130. Oxford: Oxbow Books, pp. 89-105

Schofield, Phillipp R. 2016. Access to Credit in the Early Fourteenth-Century English Countryside. In P.R. Schofield and N.J. Mayhew. (eds.) Credit and Debt in Medieval England c. 1180-130. Oxford: Oxbow Books, pp. 106-126

Wickham, Chris. 1992. Problems of Comparing Rural Societies in Early Medieval Western Europe. Transactions of the Royal Historical Society (2: 221-246)

Wolverton, Lisa. 2001. Hastening Toward Prague: Power and Society in the Medieval Czech Lands. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press

Wood, Ian. 2013. Entrusting Western Europe to the Church, 400—750. Transactions of the Royal Historical Society (23: 37-73)

Re-read the previous post:

Chapter 10 (Part 7): Tolerance of Usury for the Outsider in Medieval Christianity

St. Ambrose's tolerance to usury is akin to a just war against 'outsiders' of Christianity. Graeber argues that this conceptual equivalence was deadly for the medieval Jewish population.

These are formal written documents recording a proof of a juridical act that concerns property and the privileges accompanying it. These can be ducal, papal or episcopal or other types of authority that recorded transactions and usage of properties and their owners.