Chapter 10 (Part 7): Tolerance of Usury for the Outsider in Medieval Christianity

St. Ambrose's tolerance to usury is akin to a just war against 'outsiders' of Christianity. Graeber argues that this conceptual equivalence was deadly for the medieval Jewish population.

If you are new here, we are reading David Graeber’s Debt: The First 5,000 Years. Catch up and join us on Thursdays in 2024. My first slow read here on Substack in 2023 was David Graeber’s The Dawn of Everything. These two books showcase his thesis on the development of humanity by looking at how debt evolved and how people organised themselves and their world. Unique among his peers, Graeber still asks the big questions in anthropology.

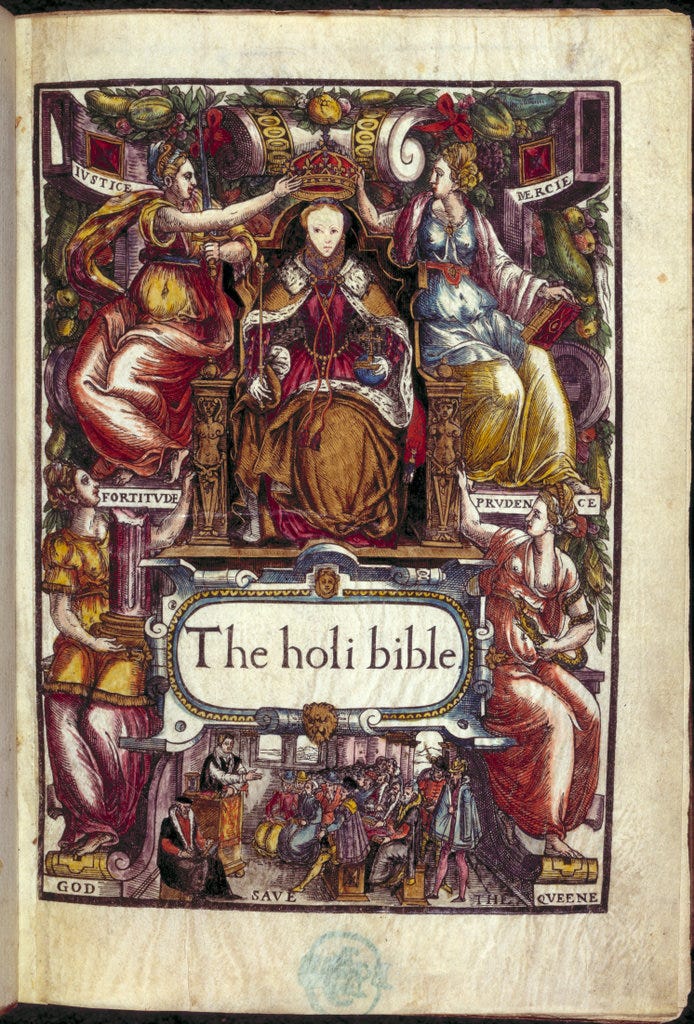

We marked AD 300 as the point in which the Western European and Asia Minor Christian communities demonstrated their institutional power. The Nicean Council, under the aegis of the first Roman Christian Emperor, Constantine, flexed its joint power by streamlining Christian orthodoxy culminating in the Nicene Creed. This has become the shared faith pronouncement across different Christian strands.

In doing so, the early Church is ultimately creating, what all religions have done, a definition of the boundaries of who belongs within the group. This becomes critical when Graeber discusses credit, debt and usury problems in medieval Europe.

Periodisation

The Medieval Period in Europe is marked after the formal end of the Western Roman Empire at the hands of Goths in AD 475. This is designated as the Early Medieval Period (c. AD 500 - 999). Prior to this, I had designated pre-AD 500 as the early organisation of the Christian Church. By the time we talk about late antiquity or the late Early Medieval Period, Christianity has become tied to the governance structure in Europe. The religious institution was poised to occupy the political vacuum after the Roman Empire.

If you had the impression about the interchangeability between Christianity and leadership power in that era it is because sacred and secular power has merged. Usury is both a moral as well as a governance problem.

Who is a stranger?

Our key question this week stems from the contradictory position of usury, profit, and interest among the People of the Book (both Jews and Christians and to some extent, the Muslims). Although usury or lending at unreasonable rates remains despised, it is also tolerated in Christianity and Judaism. Both religions share a common reference to the Old Testament.

There is an exception.

Charging interest is acceptable to those who are not your brother.

But who exactly is your brother? And who is not?

This is the conundrum facing believers from the Book: both Christians and Jews.

Old Testament

The definition of who is a stranger, and therefore, to whom you could charge is prescribed in the Old Testament. Both Judaism and Christianity refer to these sources as moral and ethical prescriptions for behaviour within the community.

Exodus 22:25

If you lend money to My people, to the poor among you, you are not to act as a creditor to him; you shall not charge him interest.

p. 283

Deuteronomy 23:19-20 states clearly that profiting is acceptable—but for outsiders.

Do not charge your brother interest on money, food, or any other type of loan. You may charge a foreigner interest, but not your brother, so that the Lord your God may bless you in everything to which you put your hand in the land that you are entering to possess.

Anyone who figures out how to overcome the irony can reap spiritual rewards.

He who does not put out his money at usury, Nor does he take a bribe against the innocent. He who does these things shall never be moved.

There are two things at play here that become ripe for endless discussion:

Charging interest rates, even potentially usurious rates, and profiting is acceptable if done outside of one’s community

The distinction between who is rich and poor determines one’s action, that is, as someone who can afford, they are called to treat those without as charitable as possible

It is clear, on paper, usury is frowned upon. However, profit-making remains attractive. It is a matter of subjecting it to another.

The Christian Church's View of the In-Group

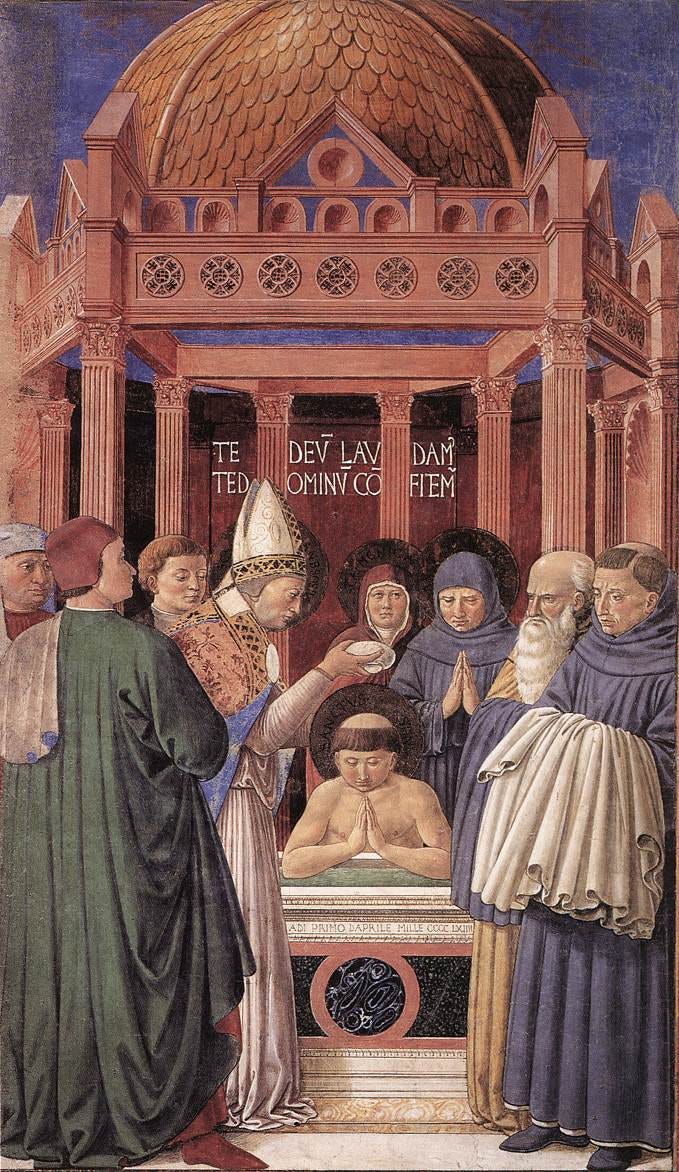

One of the earliest documented interpretations was by St. Basil (c. AD 330 - 379), the Bishop of Ceasarea in Capadoccia (present-day Turkey) whose homilies were cherished, translated and became a guideline for fellow Christian leaders.

In his homily 12, speaking about the Psalm of David against Usury (Psalm 14), he admonishes the practice of taking usury and interest, especially on those who are suffering.

Truly, the act involves the greatest inhumanity, that the one in need of necessities seeks a loan for the relief of his life, and the other, not satisfied with the capital, contrives revenues for himself from the misfortunes of the poor man and gathers wealth.

For those who had more, he expected charity or even prudence.

It was your duty to relieve the destitution of the man, but you, seeking to drain the desert dry, increased his need. Just as if some physician, visiting the sick, instead of restoring health to them would take away even their little remnant of bodily strength, so you also would make the misfortunes of the wretched an opportunity of revenue.

p. 183

His admonitions also extend to those who are thinking of borrowing

‘Drink water out of thy own cistern’ (Proverbs 5:15) that is, examine your own resources, do not go to the springs belonging to others, but from your own streams gather for yourself the consolations of life.

p. 184

So what would his answer be to what should a rich man do? Simply, be charitable. This has been the position of the ecumenical Church.

'And from him who would borrow of thee, do not turn away,' (Matthew 5:42) and do not give your money at interest, in order that, having been taught what is good from the Old and the New Testament, you may depart to the Lord with good hope, receiving there the interest from your good deeds, in Christ Jesus our Lord, to whom be glory and power forever.

p. 191

Graeber provides an interesting three-way interaction of this debt/charity relationship. Among men of unequal means, charity must be shown by the wealthy. Between a rich man and God, interest shall be accrued and paid later on.

Graeber teases out the implications of this trilateral transaction:

Church-approved charity merely reinforces the social hierarchy rather than transforming it

time is different between man and God - one lives in human time and the other in eternal time

this means that transactions can ever be only one way: man experiences sin ‘a debt of punishment we owe to God’ but God doesn’t owe man anything but can only bestow (a gift) him with grace

In this three-way interaction, we see differing forms of hierarchy. Between men, difference is enshrined. Between an immortal and a mortal, the mortal is a subordinate with a perpetual debt towards the immortal. Since the beginning of our newsletter, we have been talking about the nature of debt in Western society. We can trace the unpayable debts to its medieval roots in the early Christian formulation.

The Christian View of the Out-Group

St. Ambrose, the Bishop of Milan between AD 337 - 397, wrote several moral ascetic principles that also discussed usury. According to Graeber, he collected and analysed most of the liturgical sources on usury and related financial issues.

Ambrose’s position is extremely idealistic. He prohibits outright property ownership (‘contrary…to the ordinance of God’), charging or earning interest (‘a form of homicide’) or even commercial activities (‘distracts a man’s thoughts from virtue’) according to Barry Gordon in his Economic Problem in Biblical Thought.

Interestingly, Ambrose addressed an exception stated in Deuteronomy 23: 20 - 21.1

You must not lend on interest to your brother, whether the loan be of money or food or anything else that may earn interest. You may demand interest on a loan of a foreigner, but you must not demand interest from your brother; so that Yahweh your God may bless you in all your giving in the land you are to enter and make your own.

p. 410

In response to this rule, Gordon says, and Graeber concurs, that for Ambrose the exception is made possible by equating usury to ‘the doctrine of just war’ directed to outsiders.

Who is then the foreigner unless Amalec, unless Amorrhaeus, unless an enemy? There, it says, exact usury, whom you justly desire to kill, against whom arms are justly borne, for him usury is justly appointed. Whom you cannot easily conquer in war upon him you can quickly avenge yourself by centesima [charging interest at one per cent per month]. From him exact usury, whom it would not be a crime to kill. Without the steel he is diminished, who suffers usury: without the sword he who becomes the exacter of usury from the hostile avenges himself upon the enemy. Therefore, where there is justice in war, there also is justice in usury.

p. 115-116

Therefore, those who are outsiders and not members of the religious in-group:

can be charged interest, usurious rates or even engage in commercial activities

these same outsiders, though tolerated, are also subject to potential violence

This brings us to the High Middle Ages when the social tension between Christians and Jews came to a head.

The Consequences

Equating the practice of usury with the domain of war meant that though Jews and Christians could trade with one another and live side by side, implicitly violence was ever present. The Jewish population was periodically attacked under Christian control and power in Europe. The rules of protection and tolerance can be rescinded at any time. This can easily flip to murder and death.

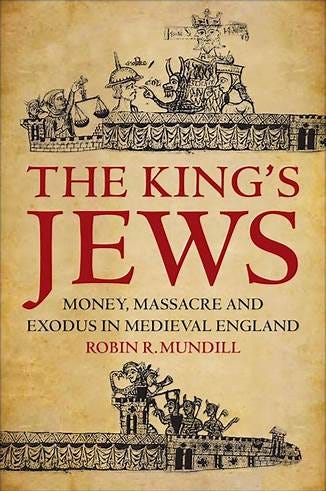

This was the case in England in the High Middle Ages when the Normans conquered England in AD 1022. William the Conqueror invited the Jews expelled from Rouen, France to join him and provide funds to build new castles among other motivations. Robin Mardil says that their status as ‘royal property’ meant that as an out-group, they needed constant Crown surveillance necessitating a branch of the Exchequer of the Jews in Westminster, Justices of the Jews, and other positions including tracking of any legal cases with Christians.

Their occupations in commerce, money lending and pawning stems from their previous experience in France. During the twelfth century, these early entrepreneurs succeeded in amassing wealth and earning attention and ire as ‘foreigners.’ Unsurprisingly, there were several pogroms against them despite being under protection:

AD 1189 - 1190 massacres of the first Jewish settlers

AD 1190 - 1290 a protection racket came about to ensure safety but for a price

Profiting off Jews became the order of the day.

A Jew who refused to pay his tax of £6,666 13s 4d was ordered by King John to have a tooth removed each day until he paid in full; it was only after the seventh tooth that he agreed to pay the sum to save his remaining tooth (Graeber identified this fellow as Abraham)

The Jews were also circumscribed in archa towns or those areas where a document filing system held in strongboxes was established for control. This ensured that all transaction records were kept on file.

They were also meant to be visibly seen as different as they were required to wear the tabula or the illustration of tablets from the Old Testament stitched on their garments.

This urban circumscription and identity control made it much easier to expel them from towns. There are too numerous expulsions to be listed here but their final expulsion was on 18 July 1290, a decree ordering them to leave England by November 1st. My list here is too simplistic as the Jewish communities were also heavily taxed for the Crusades and Crown needs. Mundill’s work is eye-opening and harrowing!

Since the institutionalisation of the Christian Church in Europe, Judaism is firmly outside of its identity. Though there is a shared disapproval over usury, in practice, defining the in/out groups meant that interest charging and profit-making proliferated in Christian Europe. The merging of the Christian Church with kingdom rule meant that the consequences became deadly for non-Christians.

Round-Up

Today we have seen how the Christian Church institutionalisation streamlined beliefs about debt, usury, and interest that has remained until today. Graeber argued that

the three-way debt interaction principles between God, the rich, and the poor (thanks to St. Basil)

how unpayable debts came about when interacting with the upper hierarchy

how ‘charity’ entrenched inequality

the creation of the in/out group made outsiders the target of usurious practices

The institutionalisation of the Christian Church is the formal creation of the insider/outsider. The early Church was still struggling to create its own identity and St. Peter wanted it to be a branch of Judaism. It was St. Paul and his mission of creating a formal branch of Christianity who wanted a unique identity separate from Judaism.

This distinction becomes critical when it came to establishing Church positions in usury and other financial matters. The clincher is the section of Deuteronomy 23: 19-20 that specified the tolerance of usury (and other forms of financial transactions) towards outside of the group (in this case, non-Christians.)

It was the words of St. Ambrose, the Bishop of Milan, who equated usury as being acceptable if it was done towards one’s enemies. This framework had violent consequences for non-Christians especially the medieval Jewish experience in Europe.

Sources:

Gordon, Barry. 1982. Lending at Interest: Some Jewish, Gree, and Christian Approaches, 800 BC- AD 100. History of Political Economy 14:3

Gordon, Barry 1989. The Economic Problem in Biblical and Patristic Thought. Leiden: Brill.

Mudill, Robin R. 2010. The King’s Jews: Money, Massacre and Exodus in Medieval England. London: Continuum Press

Way, Sister Agnes Clare C.D.P. (trans.) 1963. Saint Basil Exegetic Homilies. Washington, DC: The Catholic University of America Press

Re-read the previous post:

Chapter 10 (Part 6): The Medieval Christian Church as Sacred and Secular

Continental Europe transformed with the fusion of Christianity with kingship. The Christian church possessed the structure and political influence to take over once the Western Roman Empire declined.

Gordon explains in his work that the laws of Deuteronomy, supersedes the Code of the Covenant that enabled the Hebrews to manage their life during their Babylonian exile (c. 622 BC). This includes details on guidelines on credit and debt repayments.