Addendum Chapter 10 (Part 2): The Republic of St. Peter

The contours of the papal states resulted from defining which debt between material versus spiritual responsibility is more powerful

If you are new here, we are reading David Graeber’s Debt: The First 5,000 Years. Catch up and join us on Thursdays in 2025. My first slow read here on Substack in 2023 was David Graeber’s The Dawn of Everything. These two books showcase his thesis on the development of humanity by looking at how debt evolved and how people organised themselves and their world. Unique among his peers, Graeber still asks the big questions in anthropology.

Dear Reader,

I had not appeared on these pages but one reader misses my missives. So I am back to say that my sourdough starter has died two weeks ago and I just found out that one reason might be is the apartment might have an existing high mold colony (!!) I will have to test it again if this hypothesis is true. I hope that the two drops of vinegar will solve it.

Other cake news, I’ve been finishing a one liter bottle of farmer’s yoghurt (with a half cup still available, cross fingers!) to make this recipe which I have radically modified it through the years (and thus, get inconsistent results but I expect this!). I have made a successful run at it last week and this week (two different textures though). The taste is excellent but I hope that I unlock an easy way to make this as I have a great big bag of walnuts! (I’m hungry so I think I will try to make this today!)

I might need a new batch of cake to snack on as I stray from our chapter reading. I need a breather. I am always struggling to keep moving forward or pausing to investigate further. One of these questions is the unanswered one that has been plaguing me the last two posts: how and when did the papal states emerge?

I was able to finally track down the work of Thomas Noble called The Republic of St. Peter: The Birth of the Papal States. And also stumbled upon Steve Guerra’s History of the Papacy podcast that delved into this specific question.

Wish me luck,

Melanie

Why was it so hard to find this information?

I have been frustrated as of late because I could not find any explicit information about the formation of the papal lands until today.

What I failed to do was just simply look at the history of Rome and the papacy appeared.

The problem has gone truly local:

Rome disappeared under Byzantine history

Rome and the contours of the papal lands were rendered invisible from the Frankish kingdom point of view. (All we get is a simple Donation of Pepin, grandfather to Charlemagne as I have mentioned previously)

Thomas Noble confirmed what I suspected. I stumbled upon the Duchy of Rome and its fight to become the centre of Christendom.

Legacy of Rome: The Lateran Bureaucracy

Christianity has been in existence for four centuries before the Goths had sacked the city. It provided order and a semblance of the former Roman Empire by way of its Lateran bureaucracy.1 It was modeled after an imperial structure that also embedded a 150-year old Christian tradition of civic participation by the previous popes in Rome.

The existing ecclesiastical scrinium was described by Richard Britnell as an administrative office manned by papal notaries and defensores ecclessiae (defenders of the Church). It was the remaining active writing office that

managed the papal possessions and income

communicated with other bishops about questions on church theology

recorded papal letters since the time of Pope Leo I (AD 440 - 461) in registers that followed imperial administration protocol

maintained the papal archive

The positions were detailed in the Liber Pontificalis of the Church of Ravenna in the 7th century.

the defensor, the notary defensor, senior defensor, and superintendent of stores (horrearius)

From a letter recorded of the visit of Bishop Ecclesius (AD 522-532) to Rome accompanied by his four offices from Bronwen Neil, p. 9

By the 8th century, the bureaucracy grew into seven offices. This was called the Roman curia iudices de clero—the primary institutional units within the papacy, named after imperial dignitaries. The list of Syrian Pope Constantine (AD 708-715) included

primicerius notarorium or scrinarius is the chief secretary who supervised the notaries, the papal library and archives. The documents include the bonds, deeds, donations, exchanges, transfers, wills, declarations, manumissions (freeing slaves or serfs from bondage)

secundicarius the deputy

primicerius defensorum is the head of the defensores whose task was the legal defense of the poor and oppressed and later also took on the defense of the Church

sacellarius is the paymaster

nomenclatur is possibly the master of ceremonies of the papal court assisted by an ordinator

arcarius the treasurer in charge of financial matters

vicedominus the chief steward of the papal residence episcopium who possibly managed the chamberlains cubicularii

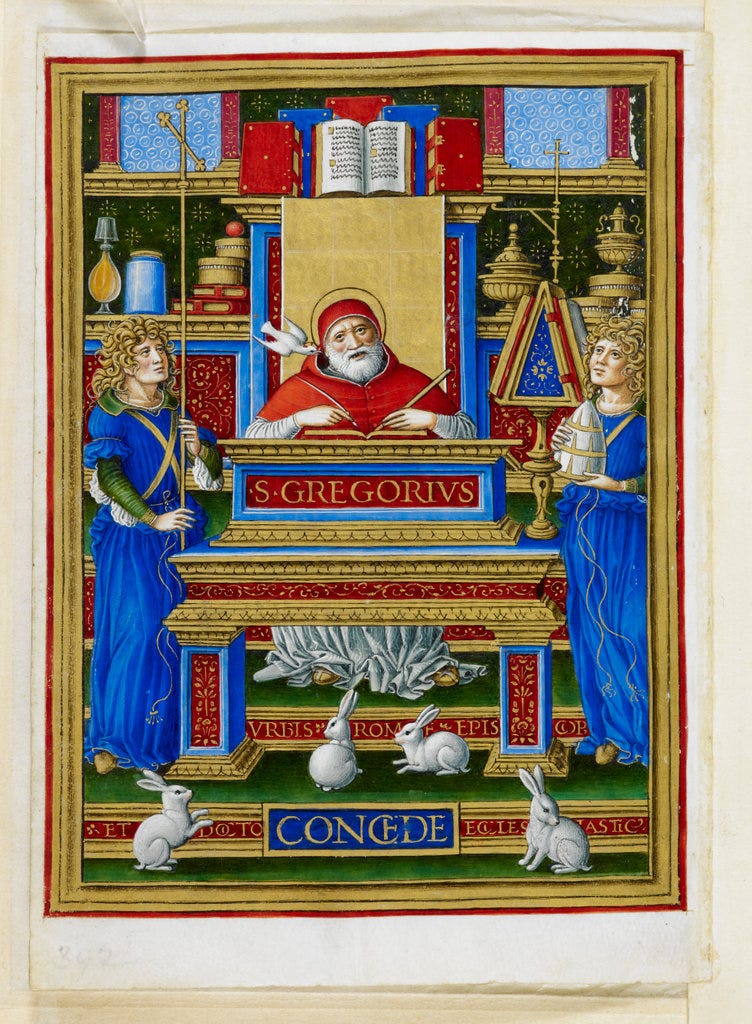

The position of the papal librarian bibliothecarius apparently was excluded from the seven offices. Neil assumes that this office has branched out from the primiricirius notarorium. There were many other offices that existed outside of the list, these included—the vestiarus, the clergy in charge of the Church’s wealth and even a personal secretary that Pope Gregory (AD 590 - 604) had, a chartularius, to whom he sent to Sicily to manage his family’s landholdings.

Despite these departments, there were few estate surveys compared to leases and other legal documents. This gives us too little archival records of Church property from that period, rarely as documented as the Abbey of Marmoutier de Tours.

His papacy is both an administrative and pastoral mission of creating a universal Christendom based in Rome, separate from Byzantine.2 This was what was called by Noble as the localisation of papal history to the history of Rome.

The papal history came to be closely tied to the concept of a Republic of St. Peter. The idea of a republic respublica romana is one of political and economic sovereignty that is bounded by Italian geographic borders (beyond the gifted patrimonies) akin to the kingdom of God on earth.

Give me my land back!

Once the Western Roman Empire fell, it was the moment to seize autonomy from multiple foreign invaders—the clutches of the Byzantine Empire (and Church), the Lombards, and the latest, the Franks.

The Republic of St. Peter is a story of debt collection between those of equal or almost equal footing. With the Lombards a continued threat, the Church under Pope Stephen II (AD 752-757) sought protection from the Franks under Pepin III (AD 751-768). They met at Ponthion (one of the royal estates in Marne, France) on 6th January 754. It was here that Pope Stephen was able to obtain a promise of defense against the Lombards but also the recovery of the iustitiis Sancti Petri, or the rights of St. Peter.

The king ‘swore an oath’ to restore the Republic including the Exarchate of Ravenna. Though the details were not specified, this promise was later confirmed in writing at Quierzy, Aisne in northern France.

It says that Pepin had promised to hand over lands…from Luni with the island of Corsica to Soriano, to Monte Bardo (i.e. Berceto), to Parma, to Reggio, to Manua, and on to Monselice, plus the Exarchate ‘as it formerly was’ (including Pentapolis, Istria, and Venetia) and the duchies of Spoleto and Benevento.

The Republic of St. Peter p. 84

This document effectively divided the territories along the Luni-Monselice line (from Liguria to Venice provinces) between Stephen and Pepin. In return, the Pope consecrated Pepin, his sons, and his line with the title of Patricius Romanorum in return for defending the Republic.

This was not the end of the debt relationship. It became an ongoing relationship between the Church and the Franks because the Lombards remained a threat.

In 755, Aistulf of the Lombards tried to block the Alpine passes but failed. Pepin crossed into Italy and besieged the Lombard capital of Pavia. With his defeat, he capitulated to Pepin and they negotiated the First Peace of Pavia. The Pope recovered Narni and Ceccano, with Aistulf promising the Exarchate of Ravenna and the Pentapolis to the Church in this treaty. The peace never held and the Church was not awarded the eastern provinces. Aistulf even attacked and besieged Rome itself!

Here, the importance of the Papal letters and the bureaucracy becomes crucial. Pope Stephen forces the hand of Pepin by writing to all the nobles in the kingdom as well as emphasising the spiritual responsibility of Pepin.

Pepin should never forget that St. Peter holds the keys of the kingdom of heaven. p. 91

Pepin exercised his iron hand but short of eliminating his rival, Aistulf, crowned him once again. However, he forced him to

hand over hostages, yield one-third of his treasury, pay an annual tribute, and swear oaths to make restitutions.

The Republic of St. Peter, p. 92

This formed what is known as the Donation of Pepin in which Aistulf was forced to hand over lands or submit it to Pepin, who in turn, gave it back to the Church.

Round-Up

The Papal Estate expansion in Central Italy is a long process commencing from the fall of Rome (AD 456) up until the Frankish rule beginning with Pepin III (Pepin the Short, grandfather to Charlemagne, AD 751-768).

The Papal Estate was not just land but it was a concept.

The Republic of St. Peter was envisioned to be a universal Christian church centred around Rome. The fall of Rome was an opportunity for the bureaucracy of the Church to provide stability and order. For four centuries prior to that, the Church had cultivated a structure modeled after its former Roman imperial ruler.

The geographic boundaries of the Republic of St. Peter was an outcome of

the fight for local autonomy of the Italian people and the papacy

the debt relationship between those of equal or almost equal power or status, that of a king and a pope

It is interesting to see how a spiritual obligation, an unpayable debt, is used as bargaining power over a material obligation. The exchange between Pope Stephen and King Pepin III over the course of several years (AD 754-756) is a struggle of power between these two types of debt. Though it appears that Pepin has a bigger hand (and he does with his armies), he needed and wanted the consecration as a moral ruler on earth and the certainty of entering heaven even more.

Sources:

Britnell, Richard. 2009. Bureaucracy and Literacy in A Companion to the Medieval World. Carol Lansing and Edward D. English, eds. Sussex: Blackwell Publishing, Inc. pp. 413-434.

Neil, Bronwen. 2013. The Papacy in the Age of Gregory the Great in A Companion to Gregory the Great. Bronwen Neil and Matthew J. Del Santo, eds. Leiden: Brill, pp. 3-28.

Noble, Thomas F.X. 1984. The Republic of St. Peter: The Birth of the Papal State, 680-825. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press

Re-read the previous post:

Chapter 10 (Part 9): Medieval Genoa: A Case of Mercantile Capitalism and Freedom

The Joint Partnership investment instrument is an equitable partnership that broke free from the credit/debt relationship

The enormous secular task was thrust upon the figure of Gregory I, Pope of Rome (AD 590 - 604), who wielded his hand against

the invasion of the Lombards threatening to fully destroy Rome

the non-action by the Byzantine for military assistance despite a representative in the Exarchate in Ravenna (their capital in Italy)

the collapse of the infrastructure, military, and civil structures leaving the management of the city on his hand

Lateran as a term used by Thomas Noble refers to the central institutions of the Church or the Republic during that period.

At that time, Rome was under the Exarchate of Ravenna, the official capital and representative of the Byzantine Empire in Italy.