Addendum Chapter 10 (Part 1): Medieval Genoa: A Case of Mercantile Capitalism and Freedom

The Joint Partnership investment instrument is an equitable partnership that broke free from the credit/debt relationship

If you are new here, we are reading David Graeber’s Debt: The First 5,000 Years. Catch up and join us on Thursdays in 2025. My first slow read here on Substack in 2023 was David Graeber’s The Dawn of Everything. These two books showcase his thesis on the development of humanity by looking at how debt evolved and how people organised themselves and their world. Unique among his peers, Graeber still asks the big questions in anthropology.

Medieval Europe caught up with the spirit of entrepreneurialism with the rest of the world:

Medieval Buddhist India that began as early as AD 1. Monasteries spurred investments and trade with what would become a medieval banking system and overseas trading. This would end around AD 854 when the ruler confiscated wealth and persecuted monks.

A separate mercantile capitalism evolved during Medieval Islam based in Baghdad. There was a two-tier financial system that tied the ruling Abbasid Empire (AD 750 - 1258) with land taxation and land grants as their means of financing the bureaucracy and army. Meanwhile, the traders operated a separate financing realm of personal networks and letters of credit that enabled them to trade overseas and spread Islam.

The story of trade in medieval Europe bears similarities to the experience in the Far East. Previously, I was surprised to find that the Church operated in different circles than the peasantry. The Church and aristocracy are linked via land acquisition and mortgaging. The free peasantry and traders had their networks of credit. It straddles the theological debate happening in the Church whereas the practice of credit and interest bloomed anyway during the ‘Commercial Revolution.’ In this period, it is as if Christianity lost the debate as the traders ascended to positions of wealth and influence.

We continue from the chapter subsection on pp. 290-293 (in my PDF copy) where Graeber discusses the rise of the European banking system and the city-states briefly. Today, I want to take a look at this and see how and where the Church and these traders intersect, if any, and the kind of credit and debt instruments they developed.

The Fragmented Medieval Italy

The pre-and medieval picture of Italy is a complex picture of successive political dynasties beyond our present scope.1 However, this early map of Italy shows the extent of localisation and fragmentation of the peninsula. This makes a single overarching storyline a challenge and impossible since the social and economic dynamics on the ground are varied at the local level.2

Note: Let’s not use feudalism

It makes it even more critical not to use the term feudalism instead of specific language such as debt or credit relations. So far, it has amazed me that none of the references I read used ‘feudalism’ or ‘feudal relations’ to describe these relationships. (Until now.) This is important because an ‘-ism’ indicates an artificial or academic framing in historiography and may not necessarily reflect what is happening on the ground. (Moreover, this term was developed in the sixties, I shall leave it to historians).

Graeber is correct. The more we use specific terms in relationships, the more we understand the transactions between people of different statuses.

We shall continue on this pathway.

Depending on the local and topical area, I will be focusing on the High Middle Ages or High Medieval Period (c. AD 1000 - 1300) but also referencing parts of the Late Antiquity or the latter part of the Early Medieval Period (AD 500 - 1000).

Tackling the Church and Merchants

Two simultaneous branches occur in our story of medieval Italy—again, seemingly operating in different realms:

the rise of the papal monarchy and the internal debate about fusing secular power and property with the sacred (this spills over with tensions with the ruling kingdoms vying for both power and position within the clergy)

the Italian city-states asserting their local autonomy over the ruling Germanic Holy Roman Emperors who were also competing against the Roman church

It appears that the theological assertions of profit and interest as sin are incompatible with what is happening and flourishing on the ground. Both cases evolved independently but also intertwined at specific points.

Two branches of power —hopefully, the twain will meet.

Branch 1: The Church

The medieval scholar R.N. Swanson begins his discussion of the key distinction in the Church in AD 1050. He marks this calendrical period as

the point at which Catholicism became a distinct tradition of Christianity

the rise of the papacy or the papal monarchy that governed Western Europe (that distinguishes itself from the Byzantine or Eastern European Church) and claimed independence from lay control in Rome and universal authority

In our previous post, we discussed an early look into an English local parish in Bedfordshire and the economic activities there. In this post, I want to examine how the papacy acquired power, particularly in the Roman peninsula.

Swanson says that the Church during this period was a federal model in which the local bishops and archbishops maintained control. Thus, the clergy directly interacted with the laity or the churchgoing public.

the local lords endowed and funded the local churches

in return, they expect to nominate or influence the priests or prelates in their parish

This is called the proprietary church or the ecclesia propria in which the lord maintains, builds and controls the church on his property. In turn, the diocesan bishop consecrated these buildings and ordained the priest. This relationship can be interpreted as the separation between material and spiritual tasks but the Church felt it was succumbing to the whims of the local aristocrats. Gradually, this arrangement was eliminated in the 12th century as the Church wanted full control and independence from any secular appointments.

This was an important impetus for the papacy to have a ‘fullness of power’ plenitudo potestatis over its affairs.

the ability to set religious beliefs and practice over all its believers

authority over its clerical hierarchy

target and suppress liturgical heresy

launch armies and crusades to recover Jerusalem but also property under the control of the Saracens

act as judge to ecclesiastical disputes and their final appeal which in canon law meant that its repository of legal decisions centralised its power

centralise all petitions, interventions and favours through the Roman curia

Rome is a special place in which the Church historically traces its unbroken leadership from St. Peter. The idea of a centralised papacy located in Rome put the bishops in a seat of control over the selection and deposing of kings. On the flipside, kings and aristocrats asserted their power over the clerical office appointments.

This tension came to a head in medieval Italy in which the Germanic Franks, successor to the Carolingian dynasty, branded themselves as the ‘Holy Roman Emperors’ and created a rival papal court (see Charlemagne). The Hohenstaufen monarch Frederick I Barbarossa (AD 1155-1190) named two anti-popes at the same time he was asserting Frankish control over Lombardy provinces and city-states. The city-states successfully defended their autonomy while providing fielty to the distant crown.

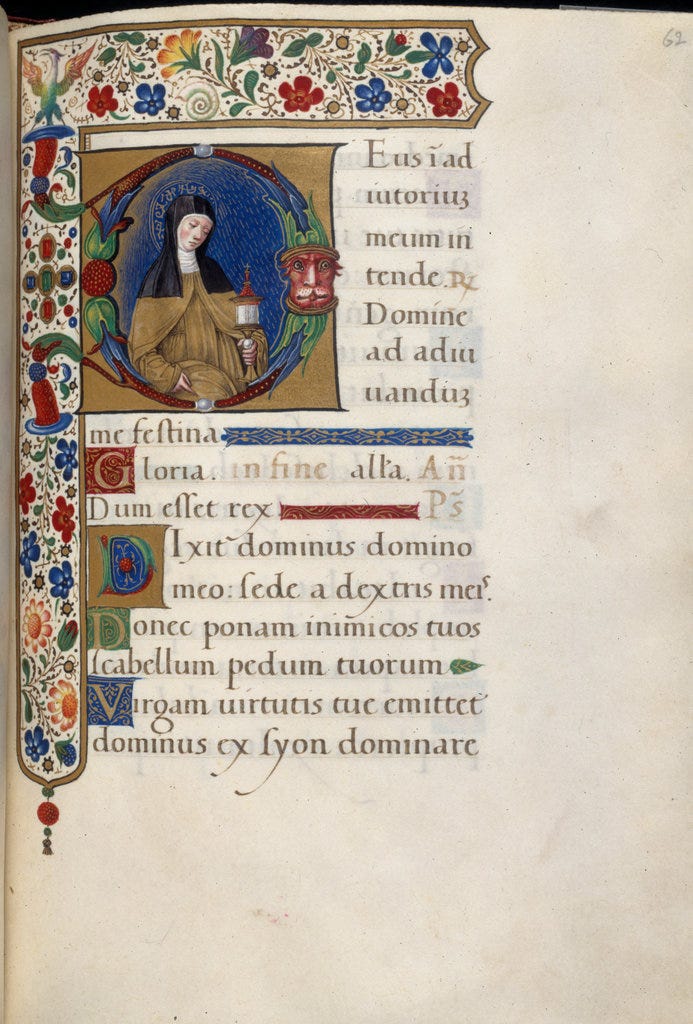

This top view belied the intimate connection between the Church with its local aristocrats. Families such as the Fieschi donated land to the Franciscans to build their nunnery led by Agnesi Fieschi, and the establishment of the Poor Clares at Santa Caterina in 1228. It is unsurprising that a member of the family was elevated to the bishopry or archbishopry. This pattern is commonly seen in other local areas in Europe.

Church activities were not monopolised by the elite but also included a large swath of the laity who performed charitable works, choral singing, and administrative tasks but also served in hospices and hospitals. These were later on organised as confraternities.

Branch 2: Medieval Genoa

The path of the Church and the citizens diverged when it came to commercial interests. In his study of 20,000 notarial minutes on commercial records, Quentin Van Doosselaere found that

five of those referred to clergy charging interest on collateralised loan

It was not clear what the loan was for but in his study, it is evident that the Church was fixed on land while the citizens were moving towards commerce. As we have seen in our previous post, the Church interacted horizontally with people in power, the local elite through its main collateral-land. In a surviving record of the Registrum Curia I shows

the Church land usufruct rights were granted in exchange for the aristocrats to provide armed escorts when the bishop traveled

the Church also collected tax on the harvest as well as the import and export of cereals

This is similar to what we have seen in other parts of Europe where Church income was tied to the agrarian economy.

Meanwhile, merchants were moving to strengthen their own Commune which made the Church organisation and participation irrelevant. According to Van Doosselaere , three notarial records by one Giovanni Scriba (AD 1154-64) became critical in this development

Charter of 958 validated landholding (including mills, vineyard, woods) acquired through inheritance or custom with the Frankish kings

Document 1056 validated the sale of landholding and alienation of land among the Genoese

Oath of 1157 in which the citizens defend the commercial interests of the trading powers as a type of social contract or the military contribution

This branching out towards commercial interests ensured that the Church had little participation in the Commune or financing.

The Commune

The Commune is a group of arms-bearing urban elite who engaged in warfaring commercial activity. There is little indication that bishops were participants. In AD 1099, the Commune started to vote in consuls who ensured military and justice administration for the eight campagna of the town. There is little indication that bishops were participants in this group. Soon enough, the commune was awarded the right to mint their coins as well as to represent Genoa internationally.

Their fierce seafaring notoriety helped protect vessels as they crossed the Mediterranean and encountered pirates. Merchant vessels do not necessarily sail with protection.

…around the middle of the twelfth century, a Genoese ship, returning from Egypt laden with precious goods, was accosted by nine galleys of Saracen pirates, the mariners, instead of surrendering, “furiously attacked the pirates with armor and sword in hand and killed almost everyone.”

from the Annales, Van Doosselaere p. 60

The Joint Partnership

One striking type of trading arrangement is what is called the commenda system. Van Doosselaere found that between AD 1154 and 1315, he discovered that 8,400 agreements out of 14,000 were made by maritime equity partnership contracts common in the Western Mediterranean. This is unique from the debt/credit relationship we have seen, so far.

These contracts were investment partnerships between an investor (commentator) and a travelling partner (tractator) who conducted the transaction overseas. The conditions, that Van Doosselaere found, were pretty standard clauses:

acknowledgement of the receipt of capital from the investors (the traveller himself may add his capital)

the standard ratio of investment and profit was one-third from the traveller (less risk) and two-thirds from the investor (bearing all the losses))

the duration of the contract was for a single voyage

specific instructions needed to be followed concerning the use of money, destination restriction or transaction of goods limitation

The interesting part of this agreement, the investments need not be in money or coinage. The Genoese were able to invest in goods instead. This allowed a broader participation of citizens who could pool their small investments. The exports included food (wine, cheese, almonds), lead, animal skins, and cloth. The value of these agreements amounted to £65 for the period AD 1154-99, £48 for the period AD 1200-50, and rising to £199 from AD 1250-1300.

Interestingly, Van Doosselaere concluded that the promulgation of the credit system later concentrated capital to a small group of specialised merchants. The joint partnership was eventually eliminated.

Round-Up

My post today echoes what we have seen in Medieval England but also in Medieval Islam. We see a convergence of credit instruments used but also several transformations that occurred with the alternatives to land as the only form of multiplier asset:

greater participation of people in the economy who were otherwise locked in

limited social roles rooted in land or military service

limited capital, small investments were possible

loosening of fixed social roles via innovative instruments such as equity partnerships

If we take the eagle-eyed view, the Church is locked in power using the land as an asset. This model has been successful in creating a long-term power/land/position relationship with aristocrats and vice versa. In this reality, ordinary people remain stuck outside of the circle. Yet, the laity is building the spiritual foundation of the church.

Commerce gave space outside of this limited circle to expand not just wealth but also roles, new activities and horizons. The merchant governance Commune was elitist and exclusionary but built a working political contract that the distant crown could not do—protect the town’s commercial interests.

The two branches circle back to charities funding the church and its community.

Sources:

Gantner, Clemens and Walter Pohl. 2021. After Charlemagne: Carolingian Italy and Its Rulers. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Rosser, Gervase. The Church and Religious Life. In Brill’s A Companion to Medieval Genoa. Carrie E. Benes, ed., pp. 345-367.

Swanson, R.N., ed. 2015a. Introduction. In The Routledge History of Medieval Christianity 1050-1500. Oxon: Routledge, pp. xix-xxxii.

Swanson, R.N. ed. 2015b. c.1050: The Starting Point. In The Routledge History of Medieval Christianity 1050-1500. Oxon: Routledge, pp. xxxiii-xxxvi.

Van Doosselaere, Quentin. 2009. Commercial Agreements and Social Dynamics in Medieval Genoa. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

Whalen, Brett Edward. The Papacy. In The Routledge History of Medieval Christianity 1050-1500. R.N. Swanson, ed. Oxon: Routledge, pp. 5-18.

Re-read the previous post:

Chapter 10 (Part 8): Credit/Debt Relations Among the Peasantry, Aristocrats and the Church

Church canon law does not reflect what is happening in the rural medieval villages or clerical activities

A quick timeline shows the level of fragmentation and localisation that still characterises modern Italy today, it was never really structurally unified:

The seventy years of the Ostrogoths whose main capital was in the coastal city of Ravenna

The Lombards from the East

The Carolingian emperor, Charlemagne united vast swaths of land that would compose his empire stretching from X to X. He was crowned as a Roman Holy Emperor who ushered in the political power of the Church in secular matters.

The successive Holy Roman Emperors

The fragmented dukedoms gave rise to the local elites and the city-states

This was the previous point made by Chris Wickham in studying medieval rural societies and its social dynamics. I am heeding his caution when it comes to narrating the regional varieties of its aristocratic and peasantry class as well as their relationship to the Church.