Addendum 2 (12.3): Rituals and Returns: China's Tributary Playbook

Why political or economic submission look like generosity in China's tribute logic

If you are new here, we are reading David Graeber’s Debt: The First 5,000 Years. Catch up and join us on Thursdays in 2025. My first slow read here on Substack in 2023 was David Graeber’s The Dawn of Everything. These two books showcase his thesis on the development of humanity by looking at how people organise themselves and their world around human values and choices. Unique among his peers, Graeber still asks the big questions in anthropology.

The China Style Tribute

For the last two posts (here and here), we have been referring to the style of the U.S. ‘tribute’ as a form of extraction. Goods and favours are granted, which tend to diminish the recipient and enrich the giver. The Philippine case is an example of how credit has been used to gain further benefits beyond the repayment. The World Bank requires ‘structural adjustment’ or policy changes that allow the economy to liberalise to its detriment. That term refers to the unseen extra credits required to attain the principal credit amount.

However, there is another style of tribute that overwhelms the recipient with goods and favours—the exact reverse of extraction—to bind them into a form of implicit submission. The effect is a form of submission and obedience that functions to produce an outward harmonious relationship. Unlike the violence of unequal exchanges between the U.S. and its former colony the Philippines, people and/or states of relatively equal standing provide an interesting contrast and dynamic.

Graeber points out the unusual relationship between the U.S. and China as dancing a different tribute tune. It is funny because you don’t know who is demanding submission. Since China holds the most U.S. bonds, it appears that China is in a precarious position vis-à-vis the performance of the U.S. economy. But are they? What is the game they are playing?

China’s Tributary Network

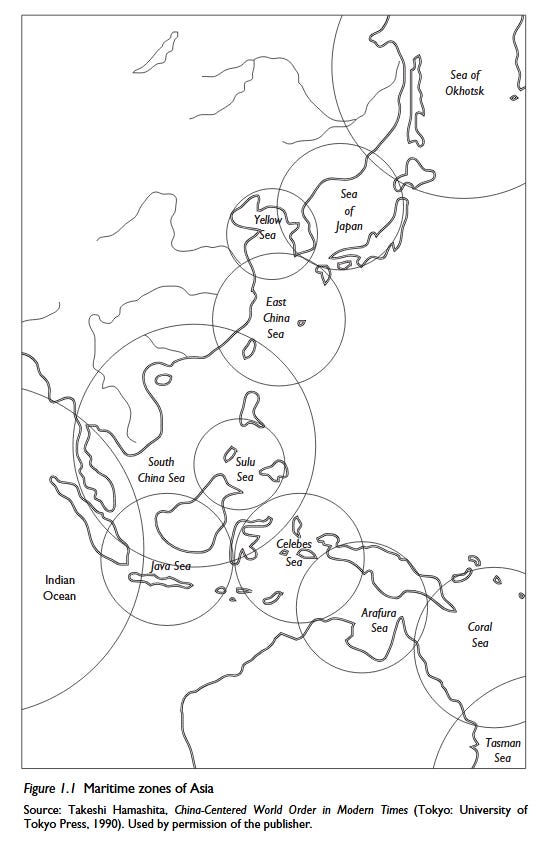

This is not the first outing for China. Graeber traces the tributary practice of China way back in the 12th century when China built its own maritime empire of trade primarily from East Asia, Southeast Asia all the way to India. This echoes the flourishing trade along port cities that we have discussed previously when Chinese goods were sought after. Outsiders desired Chinese goods of ceramics and silks. Thus, a tributary relationship seems to be a low price to pay for continued access to the market and products.

The Chinese Tribute Practice

What makes this system different and part of the Chinese?

A tributary system is more than a trade in goods. Chinese-Steppe scholar, Nicola Di Cosmo situates this in what he calls as ritualised diplomacy originating from their continental relationships with Kirghiz Nomads, one of the nomadic groups that move around the north.1 In his study of the northern land borders of the Qing Empire, Di Cosmo discusses how the Qing handled groups that are neither incorporated into their kingdom nor interested to do so. These players, though minor in the larger picture, still pose some interest but also a nuisance and minor threat along its borders. Ultimately, he argues that a tributary relationship created a political space that allowed for a loose form of control that ensures the autonomy of the tribe’s political existence but retains an unspoken rule of subordination under the Qing. They can then harness the military skills but also avert any deliberate conflict through long-term loyalty.

A tribute then is a set of ideology and cultural practices that expresses China’s positionality vis a vis its neighbours—the centre and its periphery. In this vision, Chinese monarchs see themselves as the centre, the Middle Kingdom zhongguo, in which sacred and political power rests with them. The moral and sacred role of the centre/monarchs has a long history linked to the correct performance of ritual to access spiritual power since the Bronze Period (2000-500 B.C.). Thus, ritualised diplomacy reflects the language of sacral and moral power that emanates from the core to its outlying partners.

All throughout its negotiations with other groups, the Qing uses a set of assumptions when it occupied Xinjiang in 1758.

…the language typically associated with “tribute.” That is to say, the emperor, through his representatives, would “extend favors,” “bestow his grace,” and grant gifts and honors as “encouragement to virtuous behavior” to his newly acquired subjects. Those who submitted to Qing sovereignty, be they nomadic or chieftains or urban administrators, naturally had to recognize the authority of the emperor and his boundless virtue, then had to present gifts, and bow to his representatives.

p. 353, Di Cosmo, Khirghiz Nomads on the Qing Frontier

The implicit asymmetrical nature of this relationship is continually tampered down with other forms of ritualised diplomacy that consist of marriage alliances, blood oaths, envoy exchanges, and tribute missions.

It is this same template that we see for their maritime relations with smaller territories, chieftains, and kingdoms across the region. One of them is the Ryūkyū Kingdom, an island independent from Japan, who entered into a tributary relationship with China among other polities in the region including Siam, Palembang, Java, Malacca, Sumatra, Annam, and Patani to acquire pepper and sappanwood. The Ryukyuan traders joined the Chinese merchants across the Southeast Asia or purchased the goods from the Chinese. The trade network enlarged their connections across the region and maintained their economy/autonomy until they were subsumed as part of Japan (Naha) in 1879.

The ideological and cultural practice between a centre/periphery receded as a visible marker of tributary relations when trading and economic wealth along the coast supplanted the relevance of politically kowtowing to the Qing Empire. China’s interior province has a direct impact on their maritime and overseas control. Japanese historian, Takeshi Hamashita, noted that once the interior land border weakened and their vassals revolted against the corrupt rule of local officials (tusi/tuguan) and the Office of Border Affairs (Lifan yuan) who were assigned to manage the frontier (barbarian areas or fanbu), this signaled the slow fall of the might of the Qing. He argues that the wealth brought in by the port city shifted the narrative towards a commercial/mercantilist basis of power in which the Qing had increasingly no control.

The Modern Tribute/Treaty Practice

Once the Western traders actively entered the region in the periods 1830s to 1890s, Hamashita argues that they introduced a language of treaties based on European sovereignty and nation-state territoriality. The agreements were contractual negotiations between two nations that were played out in the treaty ports. What it did was allow the Western players to enter the trading game long established in the region, such as the right to reside in these ports and compete for trade concessions.2 (This is similar to how the Hansa in the Baltics operated.)

The Qing had difficulties in imposing their control over their commercial traders as well as enforcing customs duties and officers as they were constantly being siphoned off. Suffice it to say, the Qing had fiscal problems that reduced their tributary missions from ‘once each year to once in three years respectively to just once in four years.’ There was a gradual shift from a tributary to the mercantilist model of negotiations with other cities and ports.

However, as Hamashita argues, the model of (cultural) tributary never truly went away. So if China is the largest single buyer of America’s treasury bonds, it looks like the U.S. is unwittingly in some form of tributary relationship (from the Chinese perspective). But who is playing whom?

This is the position of Graeber—China is playing the long game with its nemesis. It seems bizarre that China has to prop the dollar and the consumer power of the Americans. However, this makes sense, if Americans cannot buy their Black Friday stuff or iPhone, then it cannot power China’s production. Thus, it makes sense to support each other. Unwittingly, this has a catch, if you play the long game, says Graeber, there is a greater chance we might see the U.S. turn into a traditional Chinese client state in our lifetimes.

As I write this on June 26, 2025, it looks like this might play out in a military theatre in the very same maritime ocean of East/Southeast Asia.

Dear Reader,

I will be away next week and debating whether I should bring my laptop with me or stick to analogue. I will decide once I have suitably packed a luggage. My challenge is to keep everything light. It is hard typing on the mobile app so I will send my usual chat message as a break. I will see you again the week after.

Onward,

Melanie

Round-Up

There is another form of tributary relationship and it is couched in ritualised diplomacy. This is the Chinese form of tribute in which the principal showers the smaller and weaker polities with gifts and favours. Why?

Based on the China borders research, scholars found that China holds a specific political ideology linked to the centre/periphery dichotomy formed within their interior borders. This position assumes that the centre, the Middle Kingdom Zhongghua now Zhongguo, is the seat of civilisation and the further away you go, the more ‘barbaric’ it is. Rather than incorporate these loose conglomeration of polities, a tributary relationship helps to integrate them without the work of transformation. Loyalty is garnered through gift exchange, access to the trade networks, favourable trading terms, and a lot of other perks. The only demand is political loyalty. This buys the Qing Empire peace but also expands their skills and resources network. This form is in contrast with the hypercapitalism that we see the West enforce in the early modern period.

This historical background helps us to understand the modern relationship between the U.S. and China. The Middle Kingdom is playing a long game that involves investing heavily on U.S. Treasury Bonds that might just transform an equal into its own client/vassal state.

Sources:

Di Cosmo, Nicola. Kirghiz Nomads on the Qing Frontier: Tribute, Trade, or Gift Exchange. in Nicola Di Cosmo and Don J. Wyatt, eds. Political Frontiers, Ethnic Boundaries, and Human Geographies in Chinese History. London: RoutledgeCurzon, pp. 351-372.

Hamashita, Takeshi. 2003. Maritime Asia and Treaty Port Networks in the Era of Negotiation 1800-1900. in Giovanni Arrighi, Takeshi Hamashita and Mark Selden, eds. The Resurgence of East Asia: 500, 150 and 50 year perspectives. London: RoutledgeCurzon, pp. 17-50.

Find your way around: the book outline

Re-read the previous post:

Addendum (12.3): Haunted by Credit: 'Structural Adjustment' as Modern Tribute

Structural adjustment simply means, 'open your market for business' whether you like it or not

The other groups are the Kazakhs and the Mongols. The Kirghiz is separate from the nomadic groups that later on comprised the Manchu state which eventually evolved into the Qing Empire.

The movement to occupy territorial spaces while also trading is part of the Western hypercapitalism and casino capitalism that we have previously discussed. Europe was carving out Asia—Vietnam to the French and Burma to the British. These were colonial kingdoms shifting towards a nation-state understanding of their identity. Compare this to the monarchial occupation of the Philippines by Spain which by this period was under pressure by the modern empire/state formulation.