Slow Read Book Club: Chapter 8 (Part 1), The Dawn of Everything by David Graeber and David Wengrow

Cities without central authorities — is it attainable?

Dear Reader,

I have decided to discuss Chapter 8 in several parts to give justice to the other four civilisations that Graeber and Wengrow decided to squeeze into one. I am unfamiliar with those so it would take me time to really read through all the journals and evidence to give a more nuanced view into the puzzle of egalitarian cities.

Melanie

Scale without authority

Graeber and Wengrow enter into a tantalising proposition: civilizations did not lead to states or centralised authority like a monarchic system. Is it really possible to have a great human scale without an iron fist? The authors think so. Let’s look at the evidence and trek through lesser-cited examples of urban cities.

We are still on the hunt for an egalitarian model in (paleo and neolithic) history. We are not close by any stretch, but after seven chapters, we have a greater understanding of how humans designed to maintain that.

Combining both large scale congregation and dispersal

This is largely assisted by the Neolithic climate which allowed for a broad spectrum of animal and plant resources to be available especially along fertile landbanks of waterways in combination of herding animals

So the question for this chapter is how people maintain their egalitarian choices as populations congregated for longer periods. We’ve seen the cases in Central Europe who were massacred but also co-existing communities in Amazonia and Oceania. Now let’s turn to less known areas but also more recognisable civilisations as they grapple to maintain the egalitarian threshold for urban congregations.

Ukraine

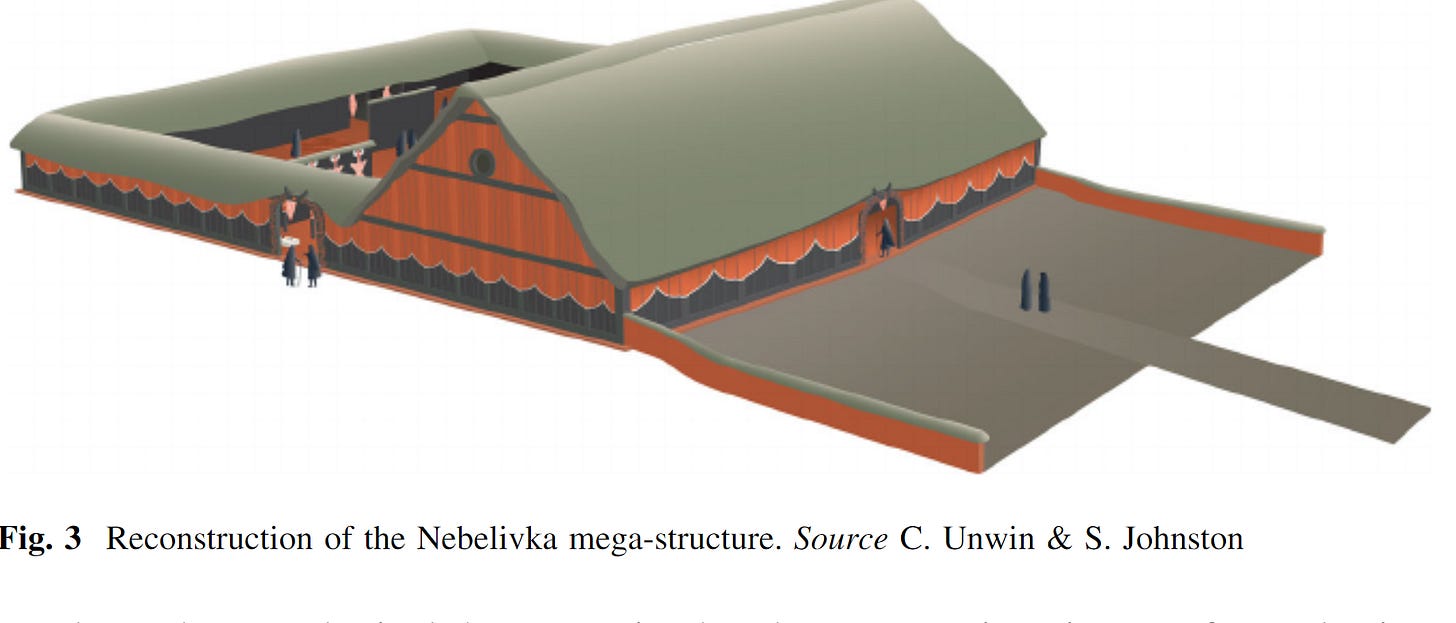

One of the least known Neolithic sites is in Ukraine. The sites of Taljanky, Maidanetske, and Nebelivka comprise what is called the Cucuteni-Trypillia culture complex group (CT) that existed between 4800 - 2800 cal BC. 1

There are 1500 houses Nebelivka, between 1600 and 2000 houses at Taljanky, and almost 3000 houses at Maidanetske covering between 100 to 150 hectares of continued occupation. Even if these were not fully occupied, the number of settlements is staggering and is one of the hallmarks of European early cities. The location is attractive for the black loam called "chernozem.’

By 4500 BC, chernozem was widely distributed between the Carpathian and the Ural Mountains, where a mosaic landscape of open prairie and woodland emerged capable of supporting dense human habitation.

A similar circular enclosure model with an empty centre is also found in Maidanetske.

What is remarkable about these mega sites is that there is no central granary or food storage at a community level. Or any centralised government ‘office’ of sorts. While there may be large two-storey houses or assembly houses, the archaeological evidence shows no differentiated finds that would indicate overt hierarchical differences among residents.

One consistent feature across sites is the predominant practice of burning structures. In the picture below, you will see burnt structures shown in red and unburnt ones in purple. Scientists still do not know why except that these seem to be related to ritualised residential abandonment.

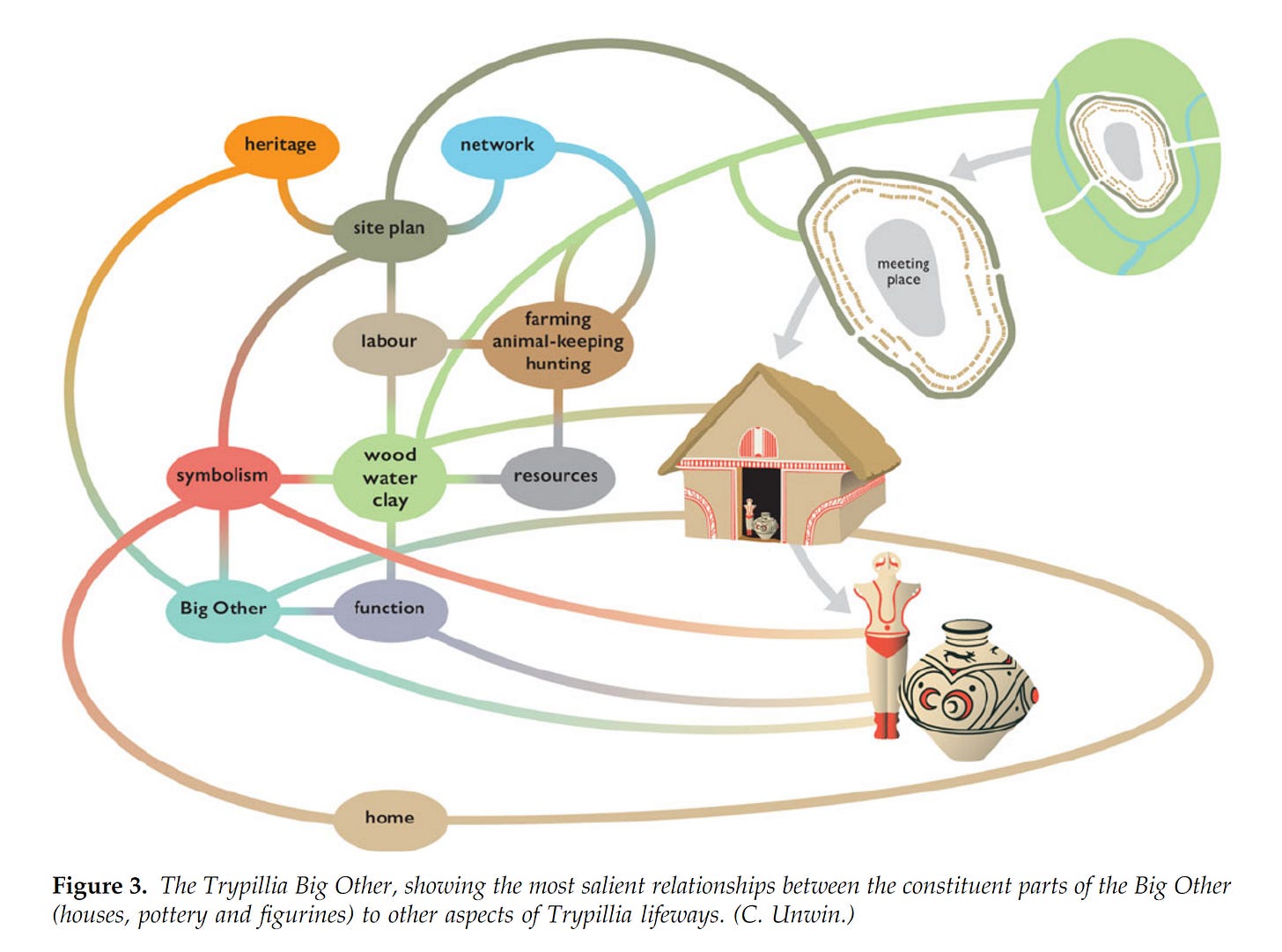

So, what keeps this mega site running? John Chapman and Bisserka Gaydarska describe the CT culture as having a model of the “Big Other” from Slavoj Žižek. They have been defined as a core symbolic order from which norms, expectations, prohibitions, and shared meaning originate. However, rather than being specific and rigid, they interpret it as a symbolic system that is sufficiently flexible for local interpretation and autonomy. This an interesting analysis of egalitarian Trypillia settlements. The authors argue for the individual and house as core centres with wider neighbourhods of a person’s worldview.

In a radical interpretation, the house is a way to de-emphasise individual prestige. The reason that there are so many burnt structures in the settlements is because of the ‘death of the house’ rituals. It is interpreted as an important final act in a complex sequential mortuary ritual upon the death of a valued member of a household. However, those that are burned are part of the house grave goods assemblage rather than any specific individual items or ownership. This includes flimsy clay figurines made to be broken as well as pieces of finely painted pottery (never whole).

Given the lack of prestige goods associated with a house burn, it would appear this argument is strong. There is little evidence of individual differentiation left as evidence. Despite spectacular performances and extravagance involved in burning, the motive seemed to be to de-emphasise any individual tribute.

Chapman and Gaydarska offer a compelling integration between the material evidence with a highly suggestive symbolic order for egalitarianism. Symbols and religion will become crucial as we discuss other more complex and famous sites.

Round-Up:

In the previous post, the years 8,000 BC - 3,000 BC were a creative but also tumultous stretch of human experimentation into urbanism and mixed agriculture. Due to a combination of geospatial and cultural factors, people were alternating between semi-permanent congregation but also dispersal. What Graeber and Wengrow call our ability to tolerate and imagine scale at the intimate but also at the grandiouse levels.

Mass societies exists in the mind before it becomes reality. And crucially, it also exists in the mind after it becomes physical reality.

The Cucuteni-Trypillia CT groups in Ukraine show remarkable imagination at scale. Not only do they congregate in large neighbourhoods, they’ve done it without any central control over another. Except maybe through a complex symbolic system centred around the individual and local household level. The house-burning ritual may hold the clue to de-emphasising any overt wealth or differentiation of families and individuals in the community. To answer our question, it seems like cities without authority are attainable as long as a shared cultural system agree to reduce hierarchical difference and an environment that can keep residents fairly independent and self-sufficient.

I hope that the researchers will persist and the site will remain intact for further study amidst the ongoing war in the Oblast region of Ukraine.

My main source is John Chapman (2017) The Standard Model, the Maximalists and the Minimalists: New Interpretations of the Trypillia Megasites.