Slow Read Book Club: Chapter 6, The Dawn of Everything by David Graeber and David Wengrow

When did elite groups and hierarchy began?

Dear Reader,

This is the toughest one yet! I struggled again with the branching and meandering arguments of Graeber and Wengrow. Plus, I am so intrigued by the research that I have come across that I think I am planning an addendum series. I don’t know yet know or how but there is a lot of obscure academic information that deserves to be in the mainstream! I am only beginning to understand the fragmented world history of people and societies that I have learned in high school textbooks.

Let this be the start.

Melanie

Tale of two neighbours

In the previous post, we read how contemporary people made specific choices to differentiate themselves and food sourcing is an important aspect of identity. Salmon hunters of the Northwest Coast had an aristocratic system that required slave ownership whereas acorn gatherers of California shunned this system.

In this post, we will learn that this pattern of cultural and economic differentiation goes far back to the Neolithic period. This is a broad period ranging from 10,000 BC to 2,000 BC and coincides with the warming and glacial retreat in the Holocene geological age. The Neolithic period is characterised by the domestication of plants and animals in different parts of the world and at different times.

The rise of agriculture or domestication of plants or animals did not happen instantly. Rather than the ‘revolution’ that we think of, agriculture is a slow chug of thousands of years prior to intensive farming in the Fertile Crescent in Mesopotamia in 3,000 BC. People were busy being creative.

The in-betweeners

Graeber and Wengrow invite us to think of pre-agriculture as a state of experimentation. Hence, they prefer readers to think of this stage as a kind of gardening and botanical observations, a type they call play farming. This is a series of decision-making in which people identify tasty and accessible plants after visiting sites over and over again. These may be considered temporary garden plots in which they would cull weeds and classify crops as herbs or medicinal drugs. The most criterion is to do as little labour as possible and use Mother Nature to water and grow the plants. It is no wonder that early cultivars spring from seasonal flooded soils along rivers, lakes, and springs.

For visual reference, I am showing how wetland wild rice (Zizania Aquatica L.) become a food resource along the river basins in the area of Minnesota and Wisconsin. Since the area is regularly flooded, no intensive cultivation or watering is required. These rice grains mature along the waterways with people collecting them during the fall season.

There was not a science of domination and classification, but one of bending and coaxing, nurturing and cajoling, or even tricking the forces of nature, to increase the likelihood of securing a favourable outcome.

For wild rice collection in North American wetlands, one individual paddles while the other knocks the stalk to loosen the grains from the stalk onto the canoe. Most of the grains fall off into the marshes which ensure next year’s crop.

This is an example of a co-evolution between plants and people.

Unseemly Neolithic neighbours

When we meet our three different Neolithic settlements in Türkiye (Anatolia/Asia Minor in history), people know:

All three are interrelated and we do not have the space to discuss everything here. The most significant point is that all these activities pre-dated intensive agriculture and monarchic states.

The Upper Fertile Crescent, as Graeber and Wengrow call this region, holds the clue to how people were deciding how to live and to politically differentiate themselves from each other.

This region is the oldest human centres of hunting-gathering, foraging, and cultivation activities. The Mesopotamian Fertile Crescent would not occur until 3,000 BC (still several thousands of years away!) We are going to look far back into human history and corroborate what Graeber and Wengrow have been arguing: that,

hunting and gathering communities were peaceful

agricultural communities reinforced inequality

During the Neolithic period, the evidence shows otherwise. This difference, as we follow their logical conclusion, would eventually lead to the system as we know it — the rise of elites, monarchic, and dynastic kingdoms later in Mesopotamia.

Unseemly Neolithic neighbours

Three archaeological sites in Southwest Asia (Türkiye)1 are key in demonstrating important cultural and economic differentiation that led to different political choices and organisations. Given that there was already existing knowledge of animal herding and selected cereal propagation,2 Graeber and Wengrow are interested in

why certain groups choose or refuse one system over another

and the resulting political formation arising out of these choices

They argue that these sites are a precursor to the rise of elites and eventually a hierarchical mode of living that will proliferate in Mesopotamia three thousand years later. Perhaps if we know, they hope we could have options to rebuild such arrangements.

Urbanising lowland hunter-gatherers

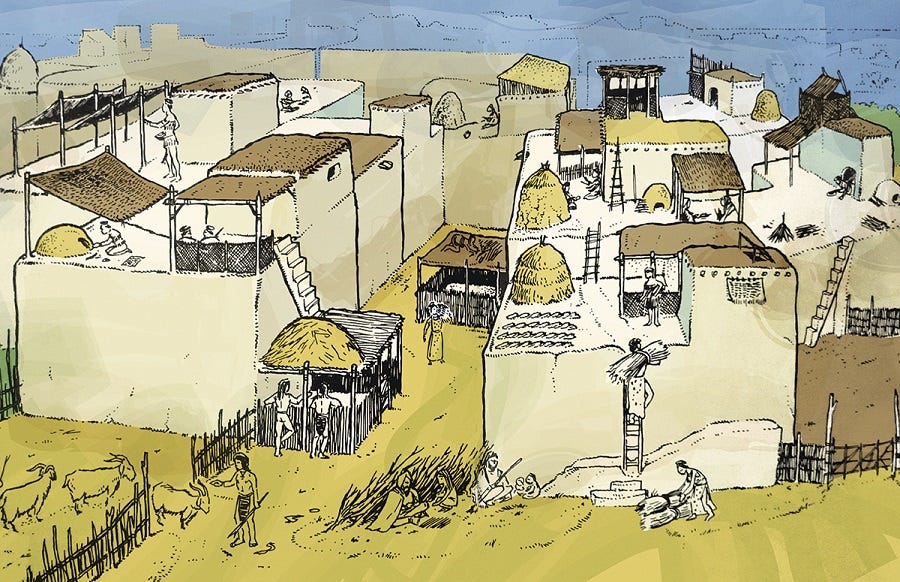

Çatalhöyük (7100 - 5950 calibratedBC) is located at the Konya floodplain with the river Çarşamba splitting the settlement into two parts the West and East Plain. The Neolithic site is the one situated on the East Mound.

Çatalhöyük is a floodplain that receives both soil nutrients from hillside deposition and seasonal flooding from the Çarşamba River through narrow channels that create pockets of water depressions in the area (Garcia-Suarez, 47-48). The mosaic landscape allows residents to cultivate plots on dry ground, graze their sheep, and collect clay for pottery and the construction of their houses. Since the location is a fragmented wetland area, wild food and shellfish sources are also available. No wonder this area has been seasonally occupied multiple times up until its total abandonment in 5950 BC.

Çatalhöyük East consists of 13 hectares (130,000 square meters) on top of an elevated mound with rectangular mud-walled houses. There are main rooms with two anterooms and a place for fire. The social organisation centred around the household level. Graeber and Wengrow are struck with the absence of evidence of central authority that runs the place with residents numbering between 3,000 to 10,000 at its peak. There appears to be a form of autonomy in terms of rites within and the routines of cleaning, cooking, and plastering the wall with clay. No distinct or ranked differences are indicated. These dwellings have been reused and buried over and over again over a millennia. Any references to cereal cultivation and animal husbandry will only appear towards the peak Middle Period of Çatalhöyük East in 6700 - 6500 BC. The early period predominantly relies on hunting and foraging.

Graeber and Wengrow emphasise the female role in these settlements.3 Commonly interpreted as fertility goddesses, they argue instead that, these are, for sure, elderly females or matriarchs who have an important societal role. No male figurine or male form in Çatalhöyük portable art has been unearthed.4

One of the more remarkable discoveries by Ian Hodder’s team was a stone figurine with similar attributes to an older female with drooping breasts and belly fat rolls.

Graeber and Wengrow note that there is more of a parity between males and females in terms of their diet, health, and burial treatments. While it might be too broad to call it egalitarian, what is clear is that there are indications of rank differences. Social prestige may be present but this did not result in elite groupings.

Urbanising upland hunter-gatherers

In contrast, the other upland settlement areas, known as the Stone Hills (Tepes) constellation of villages, show the opposite forms of social organisation. We have been introduced to Göbekli Tepe previously but now we turn to other sites similar to it but mirror opposite to Çatalhöyük East settlements.

Karahan Tepe (10,000 - 6,500 BC) lies on a limestone plateau known as the Tektek Mountains (Tektek Dagları) 63km east of Sanlıurfa.5 It was discovered in 1997 and has been subject to some illegal excavation. However, many of the architectural structures have fortunately been left untouched because they were believed to be tombs.

The location indicates a strategic hunting area with passageways that can easily be blocked.

One such trap is found 4 kilometers south of the Karahan Tepe called the Sarpdere Entrapment Area. Animals such as the gazelle, once prolific in this region, were trapped in stone pens for a significant amount of time. They were then butchered or provided a steady supply of meat or other ritual purposes for the residents and hunters in the Karahan settlement.

This is a reconstruction of the V-shaped trap noticeable with the overlapping series of stacked rocks forming the pen for animals.

The settlement itself has existing limestone features that act as walls. Unlike the swept clean floors of Çatalhöyük East houses, stone tools litter the place at a rate of 50 for every square meter. The other materials include obsidian, chisels, and adzes made from river pebbles. Other finds include stone pot fragments, grindstones, and pestles. The excavation has barely started so there is more to be discovered in the future about the social life at Karahan Tepe.

Unlike Çatalhöyük East, Karahan Tepe is known for the stone pillars erected for what Orhan Ayaz (2023: 372) hypothesises as part of the ‘hunting ground economy.’ These may be linked to the mysterious area with T-shaped pillars with animal motifs and phallic symbols.

Most notably, no female figurines or references have yet to be recovered from this site.

Karahan Tepe is contemporaneous with Gobleki Tepe and has similar structures hewn from the bedrock with carved animal and phallic-shaped pillars.

At Çayönü Tepes (8,630 - 6,800 BC), another upland steppe area is interesting because of clear cultural change in terms of gender differentiation. Similar to Çatalhöyük East, some residents were buried under house floors. The examination show that health differences were negligible. However, as time progressed, changes in their mortuary practices increased gender health differences. Using samples from about 90 human skulls and partial skeletons, the study has shown greater tooth decay among men compared to women. Men were consuming more cereals than women.

Round-Up

The findings show that those in the lowland areas show archaeological evidence of female-centred portable art and health parity between males and females. The upland regions that predominantly hunted displayed male-centric monuments. These are, of course, messy in real life as Neolithic settlements grow. There is evidence of egalitarianism or weak ranking at Çatalhöyük East compared to greater gender differentiation in the upland areas. At this point, more excavations need to be done.

Graeber and Wengrow sidestep answering how elite groups formed. The lack of clear archaeological evidence weakens their argument. However, they pose some interesting points that may lead us to the answer.

They trace the origins of hierarchy to the shift from female-centred to male-centred social orientation.

They also postulate that predominantly hunting groups create warrior prestige classes that may be the forerunners to a central authority.

The existence of two mirror-opposite groups (egalitarian and hierarchical) is inevitable; they, in fact, geographically exist side by side.

This chapter fails to answer our question directly but provides some interesting first steps to build on.

There are more but not mentioned in the book. The thesis of Aroa Garcia-Suarez is a great resource for what’s happening on the other field sites. I probably need an addendum series posting all the wonderful sources and studies that we do not have space to discuss here.

Graeber and Wengrow mix citations to include the Levant region such as their argument for female-centric art and symbols sourced from the lowland Euphrates Valley and Jordan Valleys. I have excluded them here and focused only on the upper crescent findings and their views related to it.

They pay tribute to the first female archaeologist, Marija Gimbutas, who has theorised a female-centric interpretation of Neolithic sites and the role of female goddesses herein.

The information here is taken from the two journal sources of Necmi Karul published in 2021 and Bahattin Celik in 2000.