Slow Read Book Club: Chapter 5 Part 2, The Dawn of Everything by David Graeber and David Wengrow

How did authority arise? Foragers as slavers.

Dear Reader,

Another tough post. Apparently, David Wengrow was the lead on this. Thanks to a pre-publication draft and the original journal article source, I was able to distill their central argument easily. The book chapter became a bit of a mess. I have excluded a lot of other raiding and trading groups like the Calusa of Florida or the Amazonian peoples for clarity. I enjoyed going through the photographic archives but was sad with the untold violence and loss of lives and culture. They continue though to show us invaluable ways of being human and creative political resistance beyond the archives.

Part 2: Authority and Difference

One of the interesting ideas that Graeber and Wengrow discuss is the puzzle of cultural distinction over short driving distances. If you recall, in the previous post, Paleolithic cultures demonstrated shared burial practices (using amber) but also building distinct monuments and creating symbolic art. Cultural distinction has been the norm since then and right around the corner, the origins of political authority and conflict between non-agriculturalists.

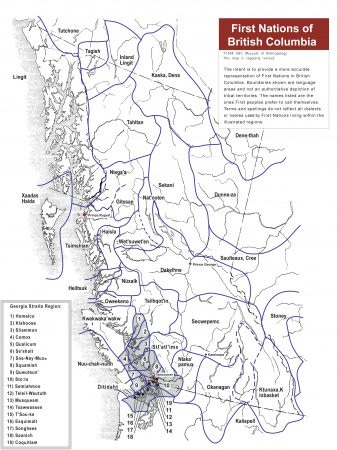

In this post, we’ll look at Graeber and Wengrow’s analysis of the experience of the First Nations on the West Coast of the USA. Much of the data here uses contact history (circa data from the 17th-18th-19th centuries) between invading Westerners and First Nations people who were also in conflict with each other.1 Outsiders like Franz Boas, the father of American anthropology, were fascinated by the origin and spread of shared cultural traits. This came to be known as the culture diffusion theory.2 He posited that geographic boundaries might explain the concentration of shared features (sweat lodges, warrior groups) and excluded others (mountain or desert environments).

However, since we began this quest, we know that forager groups are complex and mobile. They are in contact with shared skill sets and distinct practices from each other. Our default framework is no longer culture diffusion theory - it is not an exception as much as it is a rule.3 However, as Graeber and Wengrow raise, the question remains how did these traits cluster? Also, why are the Northwest foragers different from the California foragers? Dan Sperber, a cognitive scientist, answers this by arguing for a common computational mind among humans resulting in similar yet specific reactions. We possess both a genetic modular component (such as avoiding vertical falls) and are flexible enough to be context specific and adapt to relevant factors that proceed with logical steps in the most efficient way.

For Graeber and Wengrow, the answer they forward is that cultural distinctions are a result of refusal and borrowing from different groups. This choice necessarily becomes a core component of identity. Marcel Mauss, French sociologist, in his unfinished work on nationalism and civilisation, shared their view that people make a self-conscious act to refuse.4

The history of civilisation…is the history of the circulation between societies of the various goods and achievements of each…borrowing is the normal state of affairs since non-borrowing is precisely what distinguishes one society against another.

Marcel Mauss in Nathan Schlanger (2005) Techniques, Technology and Civilisation, 44

With self-conscious refusal, we now have an entry point to think about conflict among foraging groups. Graeber and Wengrow notice that few discuss the presence of slavery among forager groups. This is where our post begins.

Tale of Slavers

The western coast was said to be the largest continuous foraging people in the world from the Northwest coast of Canada to California prior to extermination with the Gold Rush and fur trade.5

The groups stretch all the way to California. Moving into more Mediterranean climates with access to land resources aside from the coast. Most importantly, the reliance on nuts and acorns.

Though they may be Pacific coastal groups, the cultural and language differences are immense between the Northwest and Californians. Not only that, the way they have differentiated from each other is reflected in their symbolic and everyday forms of art and ways of organising themselves linked to how they managed their resources.

Graeber and Wengrow observe that societies north of the Klamath River that borders Oregon and California have warrior societies with frequent inter-group raiding and chattel slavery in the population. However, this practice was relatively absent south of the river.

One of the key reasons is the nature of social status and ranking system. The Northwest Coast, particularly the Kwakiutl, possesses elaborate kinship and lineage recollection with ritual display and performance as essential to communicate these to the broader population. For wood craftsmen, spring and summer is the time they carve totem poles and tribal crests, and decorate houses and canoes.

Power comes from the accumulation, distribution, and destruction of goods as displayed during winter in a potlatch. It is during this season that these groups converge to hold complex ceremonies and disperse into smaller groups for food provisioning in the spring and summer.

These resources were amassed by select men (chieftains) from the accumulation of tradable and consumption wealth from the seasonal harvests of salmon as well as hunting various sea mammals, game, and other plant resources during spring and summer.

Some of the reasons for slavery are due to the interconnected relationship between the accumulation of goods necessary to potlatch and the harvesting of salmon. Graeber and Wengrow call ‘slave-taking as a mode of subsistence’ necessary to increase labour that would otherwise be unfulfilled by kin folk and groups. Title holders who conduct the potlatch use the same pool of kin folk. Slave-raiding becomes a shortcut to increasing labour. (Title holders acerbate the lack of labour by exempting themselves from cleaning salmon). Slave raiding steals ‘years of caring labour another society invested to create a work-capable human being’ and thereby allows title holders to gain advantage over another title holder during the potlatch.6 The archaeological evidence in this area between 1850 BC and 200AD (Middle Pacific Age) indicates high-rank distinction and effects of warfare differentiating people. Hereditary slaves numbered about a quarter of the population, proportionate to the Colonial South and classical Athens.

People Who Rejected Slavery

In contrast, the groups in California distinguished themselves by rejecting the practice of slavery. Proponents of the human ‘optimal foraging theory’ use the economic rationality framework or a cost-benefit calculation to explain why people choose one economic modality over another. However, this does not seem to fit the California groups whose staple food is nuts and acorns.

California groups have access to the same salmon farming grounds and yet, make nuts and acorns their staple food. They complement this preference by creating highly patterned baskets used for processing, storing, and serving acorn-based food. They do not possess a similar woodcarving aesthetic and instead have plain and undecorated homes. They manage their land by slash and burn to clear and prune their food sources.

Sharon Tushingham and Robert L. Bettinger propose in their fascinating study that acorns vs. salmon selection are due to storage costs associated with the food. Acorns are an example of a back-loaded resource that is easy to procure and store but costly and onerous to process. Acorns must be leached to get rid of their tannic acid and ground to create acorn meal for soup or to make bread. However, acorns are much easy to store, last longer, and are less likely to be stolen. Given the preference for population mobility, acorns are easy to transport in the absence of pack animals.

Salmon is the opposite. It is a front-loaded resource that requires a lot of labour and skill to hunt, filet, and dry at speed to preserve at the onset. Once it is dried and processed, its consumption is very easy. However, it requires a central storage unit and since it is easily consumable it becomes highly valuable to theft. It is easy to see how the Northwest Coast peoples could perform elaborate ceremonies and accumulate wealth in semi-settled housing. But it is also easy to understand why Californian peoples would prioritise acorns rather than salmon despite its availability. This would eventually reverse when they lost access to land and acorns with the encroachment by colonisers.

In-Betweeners

The Yurok is an example of a border group that according to Graeber and Wengrow could have similarly taken up raiding but reject the slave system of their northern neightbours. Though the Yurok may hold small numbers of debt peons or captives not ransomed by relatives, stories abound that disapprove of the practice. They cite Alfred Kroeber and S. Barrett’s Northwest study on the Yurok of a financial liability law to compensate for a loss of life from a raid. However, other Northwest groups like the Tlingit also have a similar legal mechanism making this reason non-plausible to explain slave rejection.

What is now left is what Graeber and Wengrow refer to as the process of schismogenesis. This is a term used by Gregory Bateson who published his work in 1936, Naven studying Papua New Guinea peoples. Schismogenesis is a social psychology term referring to the differentiation in the norms of individuals resulting from cumulative interaction between individuals (175-177). The dynamic between individuals may result in a complementary schismogenesis or one individual possessing one feature (assertive) while the other becomes its opposite (submissive). Or a symmetric schismogenesis in which a feature (boasting) becomes heightened or increased by both parties. For Bateson, these become sources of change as groups may break off from each other with both possessing antagonistic or mirror features or with similar features but competing practices.

As groups interact with each other, it is clear that some groups make political and cultural choices to be different in how they exercise and diffuse power over another.

Round-Up

All this discussion about slavery, social status inequality, and power makes us forget that these are hunter-gatherers and foragers. At the end of the day, Graeber and Wengrow do not necessarily ascribe to an economic or ecological determinism for cultural practices. Rather, they are ascribing a form of political autonomy by these people to choose the ways of living that they have. By zeroing in on the question of slavery, the authors have exposed some interesting ideas:

hunter-gatherers and foragers were never equal

political choices were made by the Californian peoples, especially by the Yurok, Karuk, Hupa, Tolowa in the border zone (shatter zone - a place of diversity) not to engage with slavery as a form of cultural distinction but also by choosing an alternate food resource that does not demand slavery

slavery was a mode of subsistence by Northwest Coast title holders because they lack the full authority to compel another to labour for his status. In other words, individual freedom remained among the population.

Northwest Coast title holders also did not do the menial task of salmon processing, increasing the pressure for greater labour.

If we take the agency of people as the starting point, as Graeber and Wengrow did, we can understand why the milieu of hunter-gatherers and foragers is complex and interconnected. They take an active part in culturally distinguishing themselves, enforcing individual freedoms against moral and economic practices like slavery, and surviving at the onset of colonial contact.

Kandiaronk wanted to ally with the French to protect them against the Iroquois attack (the Wendat eventually were forced out to Lake Huron and Michigan from New France (Canada)).

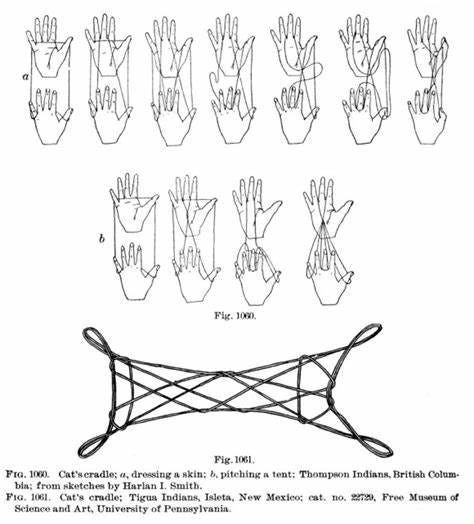

The diffusion movement was a common framework among British anthropologists in 1898 such as Professors Alfred Haddon and W.H.R. Pitt Rivers who were championing the comparative diagramming approach (inspired by First Nations’ cat’s cradle) to culture traits.

The movement on both sides of the Atlantic mimicked the natural science aims to predict and map out cultural traits like biological traits.

Graeber and Wengrow cite Marcel Mauss, a French social scientist who was a student of Emile Durkheim, as one of the early proponents that disagreed with the idea of diffusion. He argued in his writings between 1910 and 1930 that diffusion was nonsense and that movement and shared ideas and technology were normal. His idea of a cultural area characterises the exchange and distribution that occurred within a particular region such as games.

We can think further about the answer to this question especially as it related to animal domestication and other technological inventions. Marcel Mauss (Schlanger, 69) asked why the Inuits did not domesticate reindeer but merely followed them. Or the puzzle of the invention of the wheel but not its use for transport except in children’s games as mentioned by Jared Diamond in Guns, Germs and Steel.

The original source comes from Leland Donalds’s 1997 work entitled Aboriginal Slavery on the Northwest Coast of North America. For a summary, read D. Bruce Johnsen’s review and Christon I. Archer’s review. A Master’s thesis by Ian S. Urrea provides more in-depth reading.