Slow Read Book Club: Chapter 5 Part 1, The Dawn of Everything by David Graeber and David Wengrow

Why there can be hierarchy and non-violence simultaneously

Dear Reader,

I initially drafted this chapter to discuss how cultural differences led to coercive political power. I made an error and instead spent a lot of time looking into the implications of cultural differences using a deeper examination of archaeological sites. I ran out of time. I’m five hours late. Instead of deleting the work, I just decided to cut the post into two. I enjoyed finding the pictures and learning more about the sites I only briefly mentioned last time. Next week, I will zero in on conflict and hierarchies among forager groups. Stay tuned!

Melanie

Recap

Our reading for the last couple of chapters clarified the answer to the puzzle of hierarchy without authority.

Seasonal mobility means that some people preferred switching to food-rich areas and following animal food sources.

This preference among small groups of people means that cultural distinction and differentiation happened - some people will remain seasonal foragers, some will be intensive hunters, and a mix of in-between.

Cultural distinction is a political act that includes building a group’s shared beliefs and symbols. Inevitably, shared values will be different from other groups.

This is where we will continue with the story. Groups in the ancient and recent past were never equal. This chapter looks into how this dynamic worked and maybe we will disabuse our perspective about egalitarianism among pre-agriculturalists.

Part 1: We Vs. They

Early groups of people exercised their political choices to be culturally distinct from each other. Over time, this inevitably led to attempts to exercise power over another for reasons due to differences in beliefs, the acquisition of resources, or labour power.

The first thing Graeber and Wengrow advocate is to rid ourselves of the idea that those who did not take up agriculture are deviants or unprogressive. Using North American First Nation’s archaeological and historical records during the pre-and-contact period, the authors find remarkable feats of architecture and food-sourcing activities by different groups.

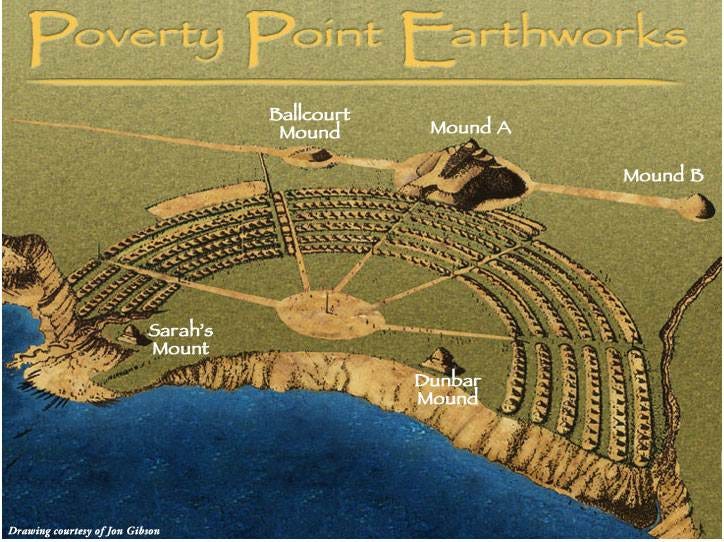

Let’s revisit Poverty Point more closely, a settlement during the time when the Beringia land bridge (8000 BC) connecting Russia with Alaska still exists (!!) and maize farming has not yet occurred until 1000 BC.

Mound A was built with 239,000 cubic meters of soil (or about 8 million bushel baskets) from elsewhere to this location within a 90-day period.1

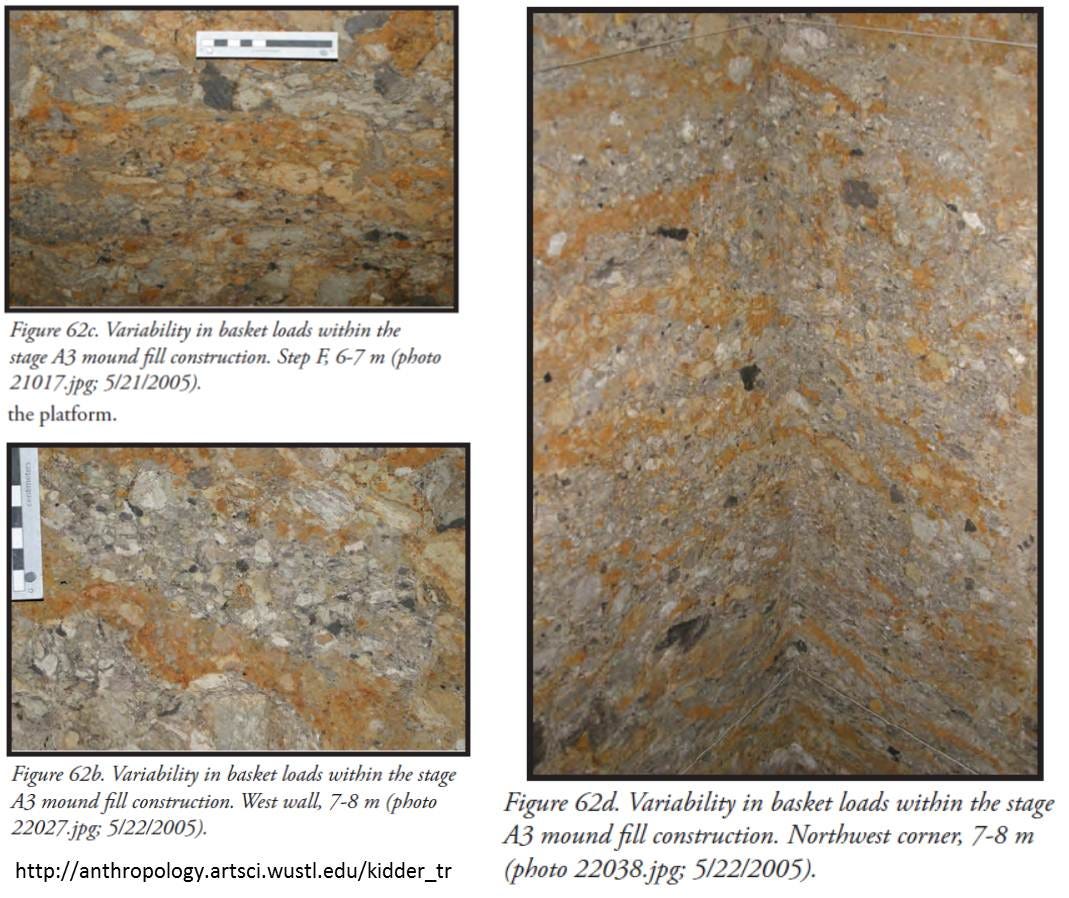

The 90-day time estimate came from the appearance of soil layer striations 6-8 meters from the top.2 The soil layers show that different types of soil were piled on top of each other and that this was done prior to any amount of rainfall on the site that would have mixed soils and erased the distinct layers. Hence, the construction of the mound indicated a short window of time.

Tristram R. Kidder and Anthony Ortman estimated 3,000 to 9,000 individuals were needed to transport soil via bucket brigade. Such a number indicates a large gathering of people and a support population for food and resource maintenance prior to the advent of states.3 Could a case of symbolic or ritual belief be enough to compel people to build monuments without coercion?

Outside of North America, some hints of symbolic beliefs seem to be an incentive to create artworks or distinct burial practices. The largest Paleolithic sculpture, the Shigir Idol, was found embedded in peat in Lake Shigirskiy in the Urals dated around 8,000 BC.

The amber-soaked burials near Lake Onega in the Karelia region of Russia, adjacent to its Finnish Karelia cultural counterpart, indicate specific burial practices using a mineral resource in the area.

The significance of amber use and discovery shows an active region of cultural distinction and possibly of sharing and trading among different groups during that period.

On the Scandinavian front, the reconstruction of a female burial in Skateholm, Sweden shows highly distinctive practices but also increasingly longer settlement decisions.

Burials indicate social distinction within the group but also across cultural groups. Taken as a cultural area, the Karelia and the communities south of Sweden may have shared and distinguishing practices. It is not far-fetched to think that contact between people is common to trade skills or goods but also the growing impetus to impose authority over another.

Recap

Let’s pause for a moment to think about these different finds. Prior to intensive cultivation, Pleistocene populations have grown to become culturally distinctive from each other. One of the more common ways to determine this is through differences in burial practices from ritual mounds in North America to amber burials in the Scandinavian area. Another is the choice in food consumption and sourcing - remaining in coastal areas or moving with herd animals. Finally, while burial is a shared general practice, there is a growing difference in beliefs, values, and symbolic systems to how this is done.

The post today demonstrates how early Pleistocene populations have hierarchical social relations without the need for intensive cultivation or agriculture or cities. It would take at least ten thousand years before it became our default food-seeking behaviour beginning in the Middle East.

One lingering question that I have is, could this really or truly be achieved without extreme coercion or power over others? Are ritual and symbolic beliefs enough to construct monuments or a common project? Part two will explore how conflict may have arisen between two groups.

Source: Archaic Native Americans built a massive Louisiana mound in less than 90 days -- ScienceDaily; original journal article by Ortmann and Kidder here

Since I have been talking about the Holocene period, I do not want to confuse you with later contact archaeological finds. At the time of Spanish and English contact, a ritual mound called Mount Royal was discovered in St. John’s River in Northeast Florida in the 18th century.

The area was granted in the name of absentee British families and worked on by plantation agents. The discovery of much older ritual mounds and shell midden sites show continuous occupation by Timucuan-speaking First Nations and much older groups. The area was later granted in the name of absentee British aristocrats and worked on by plantation agents and their corvee labour and slaves. Disease and colonisation eventually wiped out the Timacuan populations from Florida and south Georgia.