Chapter 5 (Part 3) The Moral Grounds of Economic Relations, Debt The First 5,000 Years by David Graeber

Hierarchy sits on a spectrum of violence, charity and everything-in-between that muddles our understanding of debt and morality.

Dear Reader,

This is the toughest yet but I am happy to have come to an understanding. I am excited to convey a new insight and sharpen it in the succeeding posts.

Also, you received My Life in Things newsletter in your inbox two weeks ago. It is an experiment into critical autoethnography (but really just a diary of things). It is something fun and scary for me to share. Reaching my mid-century, I have decided to be brave and tackle a critical look at why I obssess on the objects and places and the nostalgia they produce. Things encapsulate grief, elation and just sheer bliss. It is incredible to me how one object makes the past tangible and tactile in the present. I hope you don’t mind receiving these thoughts but feel free to unsubscribe from that newsletter, if you wish.

A part of my excavation project is my rediscovery of a whole trove of lost Philippine research that I hope to share with you and a wider audience soon.

On to our read today…

Defining hierarchy

Graeber defines hierarchy as relations between two unequal parties — one is superior to the other, defined socially and accepted by two parties as the terms of their relationship. This is the opposite of exchange, the struggle to reach equivalence from our previous post. Hierarchy does not presume reciprocal relations at all. Rather, it is the opposite.

Hierarchy has interesting characteristics as Graeber opines,

it is any relationship that is unequal from the start

This inequality is unlikely to be erased between the two parties. This is because hierarchy’s power stems from three cascading phenomena:

over time, hierarchy will be reproduced and transforms into a habit or custom

corollary to this, when formalised hierarchical relationships acheive habitual or customary behaviour, it operates on precedent (tradition becomes the reason for doing)

the unequal relations become enmeshed with identity (tradition becomes the reason for being), or in some cultures produce occupational caste or race relations

The moment we recognise someone as a different sort of person, either above or below us, then ordinary rules of reciprocity become modified or set aside. p. 111

Graeber describes that the transactions and gift giving relations such as one between an aristocrat and a non-titled individual relies on precedent. That is, a superior person expect to be treated differently and his inferior conforms to what is expected. In the advertisement, a lady hands over what looks to me a red box or possibly a bible (heaven’s name, it could be the pink pills that is said to cure hysteria etc.). Her gift is impossible to quantify. It does not warrant or befits the stature and wealth of the Princess. The difference in stature means that the gift cannot ever achieve any equality between the two parties. The aristocrat here is not expected to return any form of gift. Likely, countryfolks would continue to give tributes and gifts as precedent to the office of aristocracy because it has acheived historical cultural precedent accompanied by expected identity roles.1

Curiously, over time, such custom may be interpreted as benevolent reciprocal relations.

Tipping the hierarchy towards violence and ultra generosity

Graeber describes these one-sided social hierarchical relations in a spectrum. On the one end, you have the most exploitative relations — theft, plunder, and pillage. On the other end, you have selfless charity. Both these extremes demonstrate that no social relations could ever develop. It would be ridiculous to steal from your neighbour. It is safe to assume that village raiders on horseback would have no interest to form any relationship with the survivors. The point is these transactions are impersonal.

True charity is anonymous.

The reverse of the hierarchical spectrum occurs when charity mixes with theft such as when an anonymous burglar leaves presents. Santa Claus is a benevolent burglar with no possibility of forming any social relations, no debts, not just because he doesn’t exist, but he remains unidentified.

As we move along the scale of hierarchy, Graeber provides a compelling narrative of how violence and predatory behaviour transforms from extraction to moral reciprocal relations. This happens when we move from the extremes of the social relations spectrum towards the middle. Things become slightly muddled.

Violence may be interpreted as reciprocal relations as you move the needle along the spectrum.

For example, the language shift from conquest and tribute extraction by those in power to reciprocal relations is a popular theory in the origin of the state.2 The language becomes protection in exchange for material goods (via taxation). The violence becomes benign almost to the point of being forgotten. This is what Graeber rails as the invisible hand of violence lurking behind the popular moral understanding of hierarchical relations.

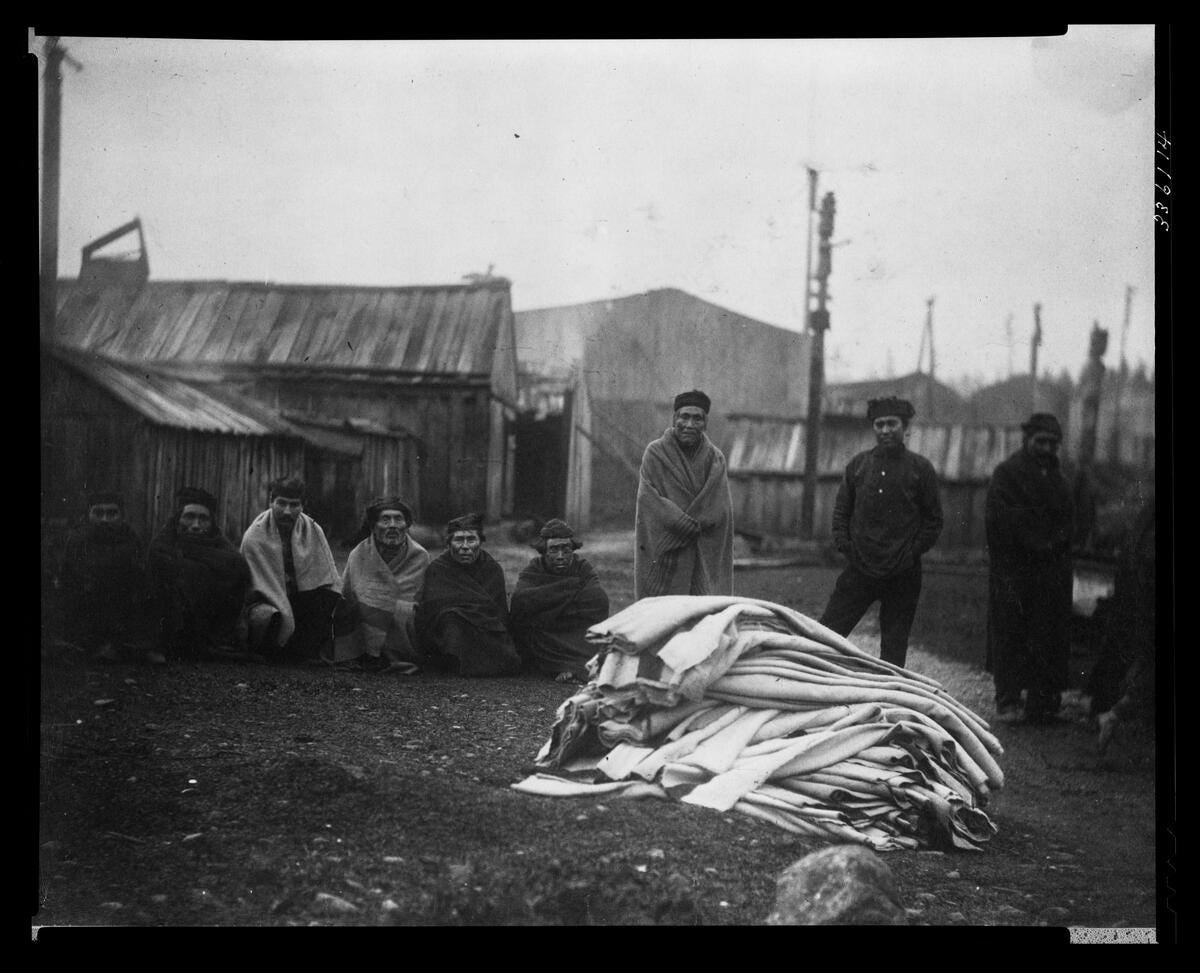

If we move the needle further along the charity spectrum, we will also encounter what Graeber calls as hierarchical redistribution. In this scenario, those in positions of wealth or power, or are recipients of gifts, are compelled to redistribute wealth as a matter of precedent. The higher the position, the greater and spectacular the return of the gift should be.

It also applies to those leaders who have plundered and used those same wealth to bestow return gifts to its subjects.

The more of one’s wealth is obtained by plunder or extortion, the more spectacular and self-aggrandizing will be the forms in which it’s given away. p.113

The redistributive state has roots in violence and war.

It is easy to see how categories become muddled along the spectrum.

The Moral Principles of Social Relations

Graeber argues that we move between the three forms of social relations: communisim or mutualism, exchange and hierarchy. These are not types of societies but rather how people interact with each other that constitute social groups.

The problem he says is,

if we look into all human relations within a reciprocity lens, then we overlook the different range of interactions

if we abstract society on a scale of justice, we tend to think of balance and symmetry, like in a reciprocal relationship

Rather, he proposes to view social relations in a spectrum in which categories switch and can transform. If we do this, we avoid narrowing our lens to just interpreting all human behaviour as reciprocity or debt.

What is debt now?

Debt can be clearly discerned in the Exchange category

it is based on the perceived equality between two individuals

the two individuals are not in a state of equality and are separated

there are means to acheive equality and bridge separation

Graeber argues that all debts could be paid or forgiven. This implies that both parties cannot walk away from each other until their relationship returns to equality. The potential for equality means that the relationship can terminate once it is paid (a cancellation, if you will).

Where does this misuse and misunderstanding of debt stem from?

Debt acquires a different modality when the two parties are unequal. This greatly affects how debt is resolved and understood.

When two unequal individuals enter into a debt relationship, the ‘law of precedent’ follows. This means that historical habits and customs triggers specific differential practices that do not necessarily resolve the issue.

For example, relations may resort into perpetual gift giving without resolution. Such a relationship may be interpreted as reciprocity. The aggrieved party brings goods over and over again without any return. This one-sided gift giving actually delivers greater pain as the debt remains unpaid and the relations perpetually strained. It is easy to assign the fault to the self. Thus, we have come to associate debt with guilt, shame and sin.

Graeber wants to untangle debt with morality that is an outcome of the laws of precedent and identity from unequal individuals. ‘Moral debt’ is one that could never be paid off. Think about the phrase, ‘debt to society.’ Graeber considers this as a false, erroneous and misuse of the term debt.

In his categories, depending on whether people are on equal or unequal footing, debt relations differ whether it is on the spectrum of ‘exchange’ and ‘hierarchy.’ Using Graeber’s approach, we can clearly see how debt can be separated from all other types of social relations. If we revisit our post on primordial debts, what do you think is happening here?

Round-Up

Communism or Mutualism, Exchange, and Hierarchy form the three categories of social relations in Graeber’s model. With the exception of mutualism, debt only enters in the categories of Exchange and Hierarchy.

The key difference is the nature of the two parties in the relationship:

exchange assumes that the two parties are perceived as equal

hierarchy recognises that the two parties are unequal

When the relations are unequal, custom or habit enters the transaction. Identity is a strong influence here. For example a relationship between a king and his subject. Based on these identities, the two parties enact behaviour defined by custom and what has happened before. This is called the ‘law of precedent.’ These practices of debt resolution are on a sliding scale of violent, charitable, and everything-in-between practices. The result muddles our understanding of debt, morality and reciprocity.

Debt, as a term, must be used as a specific imbalance that can be resolved. Graeber believes that all debts can be paid. Thereby, it should not be confused with ‘moral debt.’ Instead, his three categories create nuance in how we approach discussions on reciprocity and debt.

Precedent could enter the legal realm such that a legal admonition, a letter of non-prejudice, must be issued by the aristocrat or king to end any previously implied gift giving arrangement. p. 111

Graeber attributes this to Ibn Khaldun the 14th c. historian. We know from his work on The Dawn of Humanity that this is not the origin of the state.