Chapter 5 (Part 1) Treatise on the Moral Grounds of Social Relations, Debt: The First 5,000 Years by David Graeber

Communism, or social conviviality, generosity and sharing is the first moral principle

This is going to be an ambitious (long) chapter in which David Graeber proposes a new theory to undo the sinews that connect discussions of debt to the market and our conceptions of morality.

the logic of the marketplace has insinuated itself even into the thinking of those who are most explicitly opposed to it.

By and large, Graeber notices that much of the literature in anthropology proposes a theory of social interaction based on reciprocity, or the idea of social justice or the balancing of scales between individuals. Even gift economy theorists in anthropology, he says, focus on how debt is incurred in any gift exchange.

What he is saying is that behind explanations on reciprocity and the gift, it seems that theorists assume that it is debt all the way down. Everything between people is about inescapable exchange. Graeber breaks it down this way:

If all social interaction is about reciprocity, then assumptions of gift and reciprocity theorists go like this:

all human interaction is about exchange

debt occurs when the exchange is incomplete, delayed, or unbalanced

all human interaction is about exchange that corrects this imbalance

therefore, debt is the root of all human morality

but, is it?

In this chapter, Graeber says no, debt is not synonymous with morality.

Graeber’s new theory outlines the three moral principles that exist in different degrees in society (Communism, Hierarchy, and Exchange). These are not reciprocity, he argues.

More provocatively, let’s see how he can separate this from debt.

Communism

In quite a simplistic way, Graeber defines communism here as,

"from each according to their abilities, to each according to their needs."1

While taken from Karl Marx’s 1875 work, the Critique of the Gotha Programme, Graeber does not mean its use politically. Rather, he is referring ‘communism’ as the baseline behaviour that serves as the foundation of society. This is the ‘openhanded generosity and sharing’

between people who are not perceived as enemies

and the things shared are trivial and unimportant in themselves (hence, the generous sharing to others)

For instance, every day random conversations about giving directions or sharing a cigarette that forms the social conviviality of a group. What would be considered trivial or unimportant things for sharing is highly cultural.

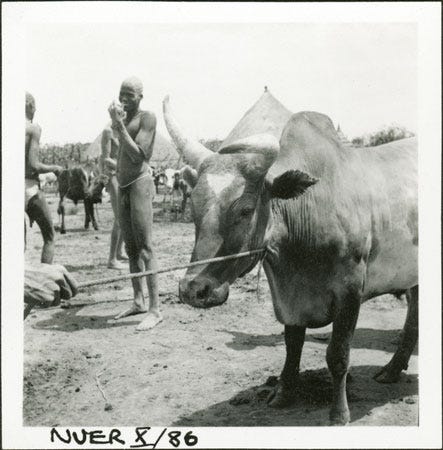

Among the Nuer of Sudan, the cattle is highly valued like a member of the family and this is not to be shared in the everyday situation.

Among the Bemba of Zambia, food sharing, for example, is socialised among children as a basic attribute of Bemba society. Anthropologist Audrey Richards saw how women scolded their children who did not immediately share any food given to them to their friends.

Unlike cattle, food, conversation, or tobacco constitutes what Graeber calls the ‘baseline communism’ that characterises everyday morality among equals. This is not the same as ‘reciprocity’ because this free sharing of mutual aid or goods among families and small groups assumes that people would do this as part of life. No thank you needed or expected. Quite the opposite of mutual aid.

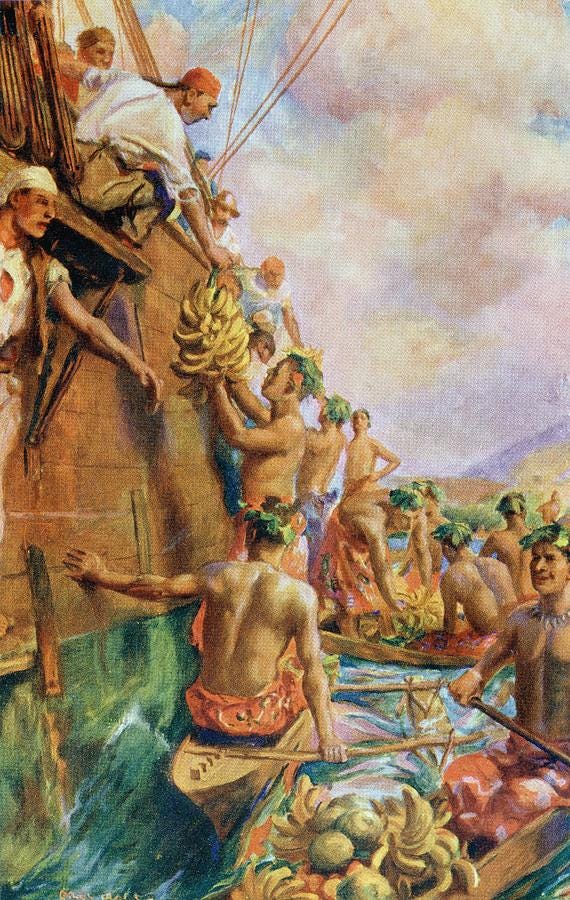

Incidentally, the English terms ‘thank you’ and ‘please’ have roots in what Graeber describes as the law of hospitality. If a stranger is a potential enemy, a wave of generosity (or hospitality) given to another erases the difference. Thus, sharing converts a stranger's relationship into a social one. This might explain why the first colonial encounters (apart from war or escape) also included flooding foreign visitors with goods. The assumption was once you accept or eat these items, you are less inclined to harm the gift giver. Unfortunately, this cultural message was contrary to the assumption of Western ideas of reciprocity, trade, and debt.

Trading was preferable to gift-giving in the Western context, as Graeber has mentioned. The erasure of sociality through zero accounting ensured that no social relationship could be developed.

You might be confused as I was when he distinguishes communism with the term reciprocity, a term to infer mutual benefit. From my reading, Graeber does not describe these as reciprocity because

these interactions do not incur debt but is simply the basis of everyday relations.

It is also not necessarily an exchange that may result in inequality.

Don’t worry, we have three parts to uncover his ideas further. I suggest reading his chapter conclusion and re-reading this sub-section on communism.

Round-Up

David Graeber sets out to build a new theory of morality outside of the language of debt or exchange.

He does not believe that all human sociality is transactions that create debt. (This is a clear example of the language of debt entering all forms of transactions when they are not).

Debt must be separated from human morality because it is a specific transaction that renders equal individuals into a state of inequality and therefore requires ways to revert the status

One of his principles of morality is communism:

Communism in this case is separate from its ties to property ownership and refers to the bottom-up organisation and allocation of resources according to one’s abilities and needs

Communism is the basis of all human relations, including capitalist relations, because we are bound by convivial interactions of sharing and generosity without debt implications

Some examples of communism typically make social life possible: helping the needy, public conversation, gossip, etc.

This same quote was used by Lewis Henry Morgan to describe the household mode of production as ‘communism in living’ in which resources are pooled and allocated among different members. Marshall Sahlins describes the household as one of economic sociability. Marshall Sahlins (1972) Stone Age Economics, p.94.