Chapter 11 (Part 4): The Virtue of Self-Interest

How credit/mutual aid was villainised and self-interest became the moral high ground

If you are new here, we are reading David Graeber’s Debt: The First 5,000 Years. Catch up and join us on Thursdays in 2025. My first slow read here on Substack in 2023 was David Graeber’s The Dawn of Everything. These two books showcase his thesis on the development of humanity by looking at how people organise themselves and their world around human values and choices. Unique among his peers, Graeber still asks the big questions in anthropology.

Dear Reader,

The death of the Pope this week reminded me that we are mere dust in the long arm of history. Death has been conquered. Death is nothing. The Pope joins all the departed members of the Church in eternal life.

Rituals have a way to unite the mourning body of the Church, but also express its hope. I remain comforted and in awe of the oldest, continuous monarchical institution in Western Europe.

the Europeanisation of Christianity

how the Church acquired its lands and became a kingdom

how the Papal States emerged

The human and sacred aspects all merge in the oldest continuous monarchical kingdom in Western Europe—with all its flaws and treasures.

I recommend the film Conclave as an imagined peek into the secretive cultural life behind the Vatican. This is a gorgeous mystery enhanced by its musical score, the cinematography, the lighting, the heightened sound effects, and the beauty of the ancient representation (I don’t care much for the ending; it’s a great thriller, though). This was my vote for the Oscar Picture.

It is best to watch the movie before this making-of featurette!

I hope to see the return to the majestic roots of the Roman arm of Christianity in the coming decade.

Onward,

Melanie

When did cash become moral and credit evil?

Despite our nascent longing to return to credit-based mutual help, as we have seen in our last post, we have uncovered the problem of the unreliable state of human nature—the preponderance of evil.

In the second half of Graeber’s argument, he puts forward the virtue of self-interest as a radical change in human relations. As we approach the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, eliminating social relationships (self-interest) will become a sign of uprightness and credit (mutual aid), vilified. Graeber says that this transformation from an economy of credit (moral networks) into interest (impersonal and self-driven) will be at the hands of the state.

Violent Roots of Debt

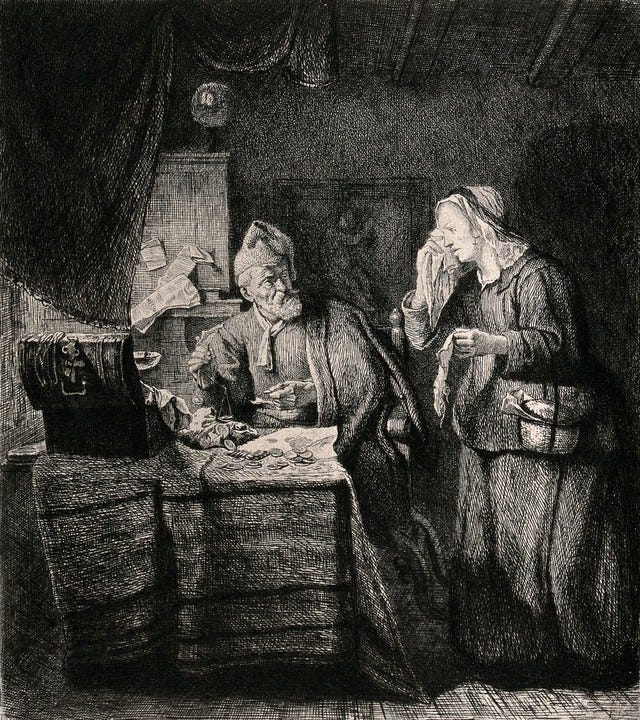

The punishment we often see in debtor’s prison is astonishing and incomprehensible. You could lose your life over a dress1, or go to jail because you were poor or a case of bad luck. What was once seen in the medieval period as a person deserving of Christian charity, historian Beier A. Lee remarked, they have become enemies of the kingdom/state.2

In medieval England, courts ascertained the sin of usury.3 According to R. H. Helmholz, the English common lawyers examined debt cases according to the Church’s canon law on usury, which covers all forms of interest on top of the principal.

It defined usury as "whatsoever is taken for a loan beyond the principal."Any gain stemming from a loan, no matter how small, was considered usurious and unlawful. The law was also strict in sanction. Offending usurers were subject to ipso facto sentence of excommunication. This entailed exclusion not only from the church's sacraments, but also from the normal company of other Christians - a real and considerable penalty under medieval conditions. Convicted usurers were required to make restitutionn of the usury to the victim or (if the victim were unavailable) to charitable uses. Unrepentant usurers were denied Christian burial, and a variety of ecclesiastical decrees struck at those who aided and abetted usurers.

p. 365-366, Helmholz

The punishment was spiritual.

Initially, the court system was used to establish a public record of the contract between predominantly illiterate villagers. At this stage, few cases were adjudicated by the court, including those of unpaid interest. It was simply bad judgment on the part of the creditor. At most, it was the threat of punishment that forced the two parties to settle out of court.

Something remarkable changed during this period.

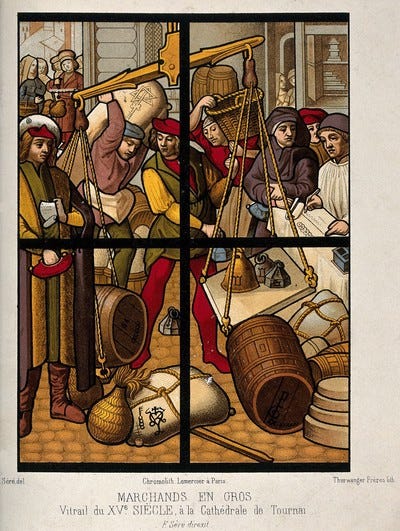

Graeber noticed that the legalisation of interest changed social relations between villagers. What was once sinful became acceptable in both religious and ordinary life.

interest-bearing loans became a common transaction

the use of signed legal bonds recognised by the court became the norm

The result was that every household was tied up in debt litigation. What was once mutual aid is now a crime.

The horrors of the Fleet and Marshalsea were laid bare in 1729. The poor debtors were found crowded together on the 'common side,'--covered with filth and vermin, and suffered to die, without pity, of hunger and jail fever . . . No attempt was made to distinguish the fraud ulent from the unfortunate debtor. The rich rogue-able, but unwilling to pay his debts-might riot in luxury and de bauchery, while his poor unlucky fellow prisoner was left to starve and rot on the 'common side"' (Hallam 1866 V:269-70.)

p. 447 (endnotes), Graeber

Credit became a criminal matter. Tawny Paul documents how creditors’ access to the debtors’ goods and assets via common law became expensive and slow. Incarceration then became efficient and cheaper. He argues that this form of punitive measures against debt affected those in the middle who never had the chance to regain their former standing.

The violence of incarceration occurs on multiple levels: the additional fees for sustenance during incarceration must be paid by the family, the limit on livelihood opportunities for debt recovery, and the lengthy prison terms (in London’s Fleet prison before 1780, about half of the incarcerated have sentences up to four years or more! See, Woodfine)

Impersonal cash transactions, or self-interest, gained a reputable moral high ground compared to the uncertainty in credit.

The Virtue of Self-Interest

Self/interest and self/love as virtues became part of mainstream thought through the market. Adam Smith (1723-1790) became its proponent in his Wealth of Nations. The analysis of Craig Muldrew looks at how self-interest in the market is a moral imperative that, in the end, creates the good for everyone. How this happens in Smith’s formula, according to Muldrew, is as follows:

modern individualism (self-interest) comes at the breakdown of communities

individual capital accumulation (reduction in reciprocity)

productive capacity increase via profit-making makes everyone wealthy

Whoever offers to another a bargain of any kind, proposes to do this. Give me that which I want, and you shall have this which you want, is the meaning of every such offer; and it is in this manner that we obtain from one another the far greater part of those good offices which we stand in need of. It is not from the benevolence of the butcher, the brewer, or the baker that we expect our dinner, but from their regard to their own interest. We address ourselves, not to their humanity but to their self-love, and never talk to them of our own necessities but of their advantages.

II.2, Smith

This fascination of the rational man and the market-driven division of labour became the tenets of the field of economics. Rightfully, both Muldrew and Graeber agree that this is a false promise since trust is a prerequisite of every trade and the contract. Thus, Graeber describes the idea of cash as king of Adam Smith as a utopia.

Round-Up

How did credit become evil?

Graeber traces its demonisation of credit to the legalisation and regulation of interest (usury) by the English court system in the sixteenth century. The religious template of mutual aid and charity morally shifts when credit enters the legal system. The hand of the state, through incarceration, punished debtors in extreme measures. The nature of physical and social violence imposed by the kingdom/state led people to fear the debtor’s prison. This fear and brutality extended to the ruthless behaviour exhibited by conquistadores such as Hernán Cortés in South America. Deeply indebted, Cortés never enjoyed lasting financial success. His constant bankruptcy eroded his precarious middling status.

As a result, impersonal cash transactions emerged as morally superior. It reinforced the concept of the rational economic man, which came to be the basis of Economics today. This remains, of course, a false virtue and utopia. It masks the necessity for trust while obscuring the underlying violence of the king/state.

Sources:

Beier, A. Lee. 2024 [1985]. Masterless Men: The Vagrancy Problem in England 1560-1640. Oxford: Routledge

Helmholz, R.H. 1986. Usury and the Medieval English Church Courts. Speculum 61(2): 364-380

Muldrew, Craig. 1993. Interpreting the Market: The Ethics of Credit and Community Relations in Early Modern England. Social History 18(2): 163-183.

Paul, Tawny. 2021. Losing Wealth: Debt and Downward Mobility in Eighteenth-Century England. In David Hitchcock and Julia McClure, eds. The Routledge History of Poverty, c.1450-1800. Oxford: Routledge, pp. 103-119

Pound, John. 2013 [1971]. Poverty and Vagrancy in Tudor England. Oxford: Routledge

Smith, Adam. 1852. An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations. London: T. Nelson and Sons. Public Domain

Woodfine, Philip. 2006. Debtors, Prisons, and Petitions in Eighteenth-Century England. Eighteenth-Century Life 30(2): 1-31

Find your way around: the book outline

Re-read the previous post:

Chapter 11 (Part 3): The Christian Roots of Self-Interest and Capitalism

The quantified ideas of self-interest and capital growth in Florentine accounting trace back to St. Augustine's self-love

Graeber’s example talks about Margaret Sharples from Chelsea in 1660, who was prosecuted for stealing cloth. She initially negotiated for a credit purchase with the shopkeeper. He initially agreed but reneged on his promise and filed legal proceedings.

The vagrants and vagabonds, or highly mobile people not tied to any land or landlord relationship, became the target during 1560-1640. He points out that this period was the height of vagrancy in Tudor and Stuart England. Another historian, John Pound, traces the root of poverty to the floating population prior to the onset of the Industrial Revolution.

The government and church existed side by side, extending and enforcing charity. In this case, the law implemented the prevailing church's policy on usury. This gave rise to the contours of a state apparatus, especially in England.

Your words keep me going, David! I was astonished how self love and self interest are very similar, if not the same! This was the missing link in my head between Christianity and capitalism.

Very interesting, well researched essay. Thanks for the effort 🫡👏