Chapter 11 (Part 1): The Bottomless Metal Sinks of Asia

Did Western Europe radically innovate its capitalist practices because they were economically lagging behind Asia—the economic superpower?

If you are new here, we are reading David Graeber’s Debt: The First 5,000 Years. Catch up and join us on Thursdays in 2025. My first slow read here on Substack in 2023 was David Graeber’s The Dawn of Everything. These two books showcase his thesis on the development of humanity by looking at how people organise themselves and their world around human values and choices. Unique among his peers, Graeber still asks the big questions in anthropology.

Dear Reader,

You know it is sunny spring when the ice cream shops re-open. I am still quite fascinated by how a business can shut for half a year and simply reopen for spring and summer seasons! They remain open until October and still survive despite paying for rental space during their shuttered winter season. They don’t even attempt to sell coffee during the cold months.

I am waiting until Easter to have my favourite flavour—cerise!

I haven’t visited my new Dune cafe, but I am waiting for my cough to go away and get stronger. It’s a slightly longer bike ride.

Onward,

Melanie

Andre Gunder Frank’s work reframes the Age of Exploration between 1450-1800 as dominated —not through naval expeditions alone, but through wealth absorption. Nowhere is this clearer than in the flow of silver bullion from West to East; a remarkable paradox emerged: Western Europe spiralled into inflation, while Asia absorbed immense amounts of silver without destabilizing its economy.

In the coming weeks, we shall explore how Western Europe managed to reverse its fortunes.

Inflation in the West

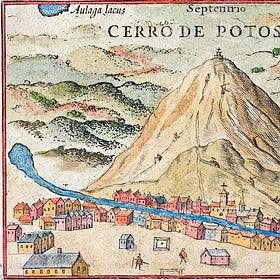

The Age of Exploration between 1450 -1800 is also the Age of Extraction—the flood of silver and gold extracted from South American and African mines triggered inflation across Western Europe between 1550 and 1700, destabilizing prices.1

The flood of bullion in the continent shifted to how money as a symbolon was conceptualised and materialised. For Graeber, the shift towards metal as money imposed difficulties:

taxes had to be paid in metal; yet, ordinary people did not have access to them—the government, bankers, and large merchants controlled the bullion and did not circulate it in small communities

gold and silver became the basis for credit and paper money arrangements replacing trust-based financial relations

Between 1660 and 1700, prices stabilized. Econometricians Edo and Melitz hypothesise that, before this period, European governments exerted minimal fiscal influence. It was only later that states could leverage credit for warfare and allied expenditures. This is also one of the arguments put forward by Richard Bonney et. al. that creating wealth became possible. When a fiscal apparatus began to emerge—a permanent and reliable taxation system and government’s ability to secure long-term credit—in England and Western Europe, an economic stimulus was possible. Unsurprisingly, the combination of a state model with credit, and financial instruments were factors that led to an industrial-scale machine-based manufacturing economy.

What we see is the bust and stable cycles. But we’re getting ahead.

Boom in the East

As Gunder Frank and others he cited have pointed out: Asia was the place to be. Europe was too peripheral to join in the fun. After all, Europeans were rabid consumers of Eastern commodities and luxury goods, namely, Chinese silk, porcelain, and spices. Much of the silver bullion harvested in South America was destined for Asia—about 32,000 tons between 1545 and 1800. This figure rapidly grew to an aggregated 48,000 tons from Europe and Japan with an addition of 10,000 tons from the Manila-Acapulco (Mexico) galleons for two and a half centuries until 1700.

That’s a lot of silver.2

Yet India and China, two of the metal ‘sinks’ or destinations, escaped inflation.

The two main reasons that Gunder Frank identified were the population and production increase that absorbed the volume of silver. An example for both India and China is textile production.

China

The economy of China is geared towards local production and consumption. We see the rapid land transformation of crops and sericulture (silkworm production) to satisfy both local and export demand. The production of cotton alongside silk and sugar was a significant commodity that absorbed the bullion imports. Farmers planted sugar cane alongside rice. Forests were replaced in 1700 with mulberry trees for the silkworms.

Cotton seeds came from India via the Silk Road and have been cultivated since the 9th century in Canton (Guangdong) and Fujian provinces. The cultivation quickly expanded northwards in non-tropical humid climates in the Yangtze River, Sichuan, and Shaanxi regions by 1270-1300. Government control was essential to keep the value and cultivation of silk high in the North. However, this ultimately changed when the Yuan dynasty incorporated cotton as part of their tax system and quotas. The kingdom purchased as much as 15 million bolts annually before 1400 for military apparel (see Zurndorfer 2009 but also early draft). Its export, especially the ‘nankeen,’ came to be equally valued for its fine workmanship.

Notably, Graeber pointed out the Ming Dynasty’s (1368-1644) aversion to foreign merchants so much that it tried to control the economy and trade. However, this was disastrous as it restricted people in their occupation to promote self-sufficiency, and rendered commerce illegal, with the consequence that the agricultural sector was heavily taxed. This spurred the indebted farmers to flee and engage in odd jobs—silver mining was lucrative. It created a host of illegal mines with off-the-books informal economy which the government tried to shut down in the 1430s and 1440s. This was met with resistance and the government loosened financial control of minting silver, issuing paper money and idea of labour restrictions.

As a result, the market flourished; the population increased with better living standards unique for that time.

India

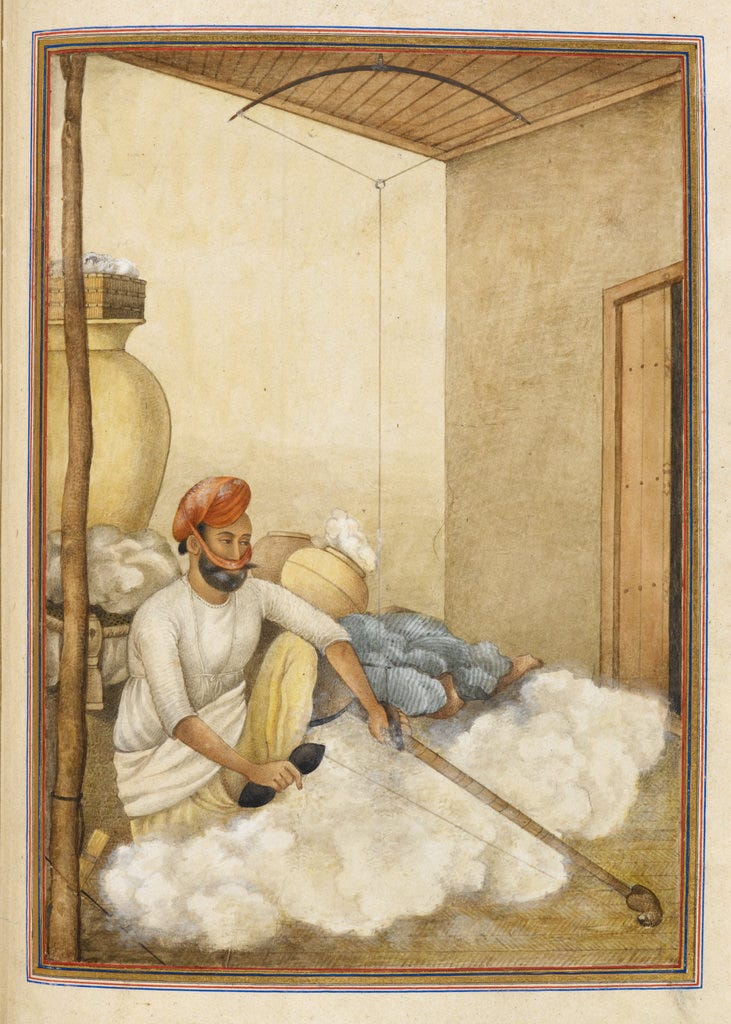

Similar to China, India had a high production and capacity to absorb the amount of silver flowing into the country. This is linked to their world-famous Indian cotton textile—from gossamer muslin to heavy-weight cotton chequered patterns—shipped from the east in the Bay of Bengal, the southeast Coromandel coast and to the west in Gujarat. India had an integrated system of planting, processing, dyeing and weaving across the land with enough area for agriculture to feed its workers. In one estimate, the number of workers in the Bengali industry reached up to one million with as few as ten per cent dedicated to the British and Dutch East Indies companies. The rest went towards internal consumption and mostly intra-Asia and Middle Eastern trade.

The amount of silver was easily absorbed at the village level where people were paid wages on a daily and monthly level. The country was highly monetised. Women and the household were active participants with caste and specialists engaged in cleaning, spinning, and weaving the fibre.

The entire industry spurred the population growth and the urbanisation of areas all linked to textile manufacture. This meant that land use was maximised and deforested especially in the case of Bengal by the end of the seventeenth until the eighteenth centuries for cotton.

Europe remained largely peripheral in Asia’s flourishing trade networks. Without the influx of South American silver, Western Europe would have struggled to access the Eastern markets. In response, Europeans turned to alternative strategies—economic innovation and force—to alter their global position. This European strategy is what Graeber narrates next—the use of violence and terror—to compete.3

Why then did hyper-capitalism emerge in the West?

I revisit this question to stack our knowledge. Economic historians describe a flourishing Asian age that developed technology to produce high-quality and sophisticated commodities. Textile is one example where cotton as a plant can only be cultivated in semi-tropical regions but also proves to be durable and with expert craftsmanship became a highly sought-after material.

The rise in consumerism in Western Europe during this period perennially created an economic deficit. Given this challenge, Europeans sought other means to overcome the imbalance by searching for precious metals elsewhere.

What is missing are other factors:

What role did Christianity or Christian humanism play in the development of science (especially since Europe was way behind in technology)?

Was the economic deficit in the world economy a catalyst for the industrial form of capitalism (in England) unnecessary in the wealthier parts of Asia?

After all, if Greater Asia was wealthy and could still absorb more silver into their economies without problems, was this a disincentive to innovate?

Round-Up

We continue to understand why the Greater Asian region—ranging from the Middle East, and India, to the Far East (China and Japan) had economic dynamism. It produced the goods everyone loved to have. Take the case of textiles and the industry that developed around it. It integrated the interior with the coastal cities—from production to finished product—and linked households with coastal and inland merchants. India and China had room to grow and absorb the silver flowing in and redistributing it all across the population.

We are left with the Western European problem of how to participate in this economy when it had few products to export yet had a huge appetite to import Eastern goods. Economic historians indeed point to the need to find silver metal elsewhere. And it did. But it also had to innovate in other ways. The revamp of a fiscal system that ushered credit as the leading source of wealth for sovereigns.

Sources:

Gunder Frank, Andre. 1998. ReOrient: Global Economy in the Asian Age. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Riello, Giorgio and Prasannan Parthasarathi, eds. 2009. The Spinning World: A Global History of Cotton Textiles, 1200-1850. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Find your way around: the book outline

Re-read the previous post:

Chapter 11: Age of Extraction: The Money and Metals Grab

Is it as simple as a money grab that explains Western European expansion?

Other reasons include population recovery and growth and urbanisation that fuelled agricultural food prices—up to 7 fold. See, Edo and and Melitz (2019).

The European angle is dwarfed by the trade between Japan and China and the silver that flowed into China’s coffers.

…the Japanese silver exports to China were…on average six to seven, times greater than which arrived across the Pacific from the Americas,…8,000- or 9,000 ton total…between 1560-1640.

Gunder Frank, p. 146

This amount is 30 to 40 per cent of the 28,000-ton total entering China at its peak.

I did not want to forget this detail I read from Zurndorfer’s draft, p. 22. It is the easiest explanation of the opium trade I have ever read. Even if it is outside our period (1818-1833), this example of an economic deficit. It is serious. The East India Company or Britain was in a perennial deficit due to the purchase of other Chinese goods aside from trading Indian tea and textiles. It resulted in an imbalance of $13,228,161 which opium from India paid for at the sum of $104,302,948. This gave Britain a $91,073,987 trade surplus. Clearly, drugs were profitable. Figures from David Bello’s Opium and the Limits of Empire p. 38.