Chapter 10 (Part 1): The Middle Ages (AD 600-1450)

The fall of the Roman Empire broke the military-coinage-slavery complex. What follows is a loose conglomeration of kingdoms with little use for coins.

If you are new here, we are reading David Graeber’s Debt: The First 5,000 Years. Catch up and join us on Thursdays in 2024. My first slow read here on Substack in 2023 was David Graeber’s The Dawn of Everything. These two books showcase his thesis on the development of humanity by looking at how debt evolved and how people organised themselves and their world. Unique among his peers, Graeber still asks the big questions in anthropology.

Dear Reader,

Next week I will be away. We shall have a momentary pause.

I just finished a gripping thriller (easy read, immersive, like a podcast but better) called, The Nothing Man. Highly recommended piece of escapism (with minimal gruesome events) set in Ireland. I cannot believe that you can cook and read, but you can!

Right now, we’re embarking on a new age where the armies have collapsed. The coins were supposedly gone. The military regimes fall. And in its place are organised religions.

Another long journey towards the Middle Ages.

Melanie

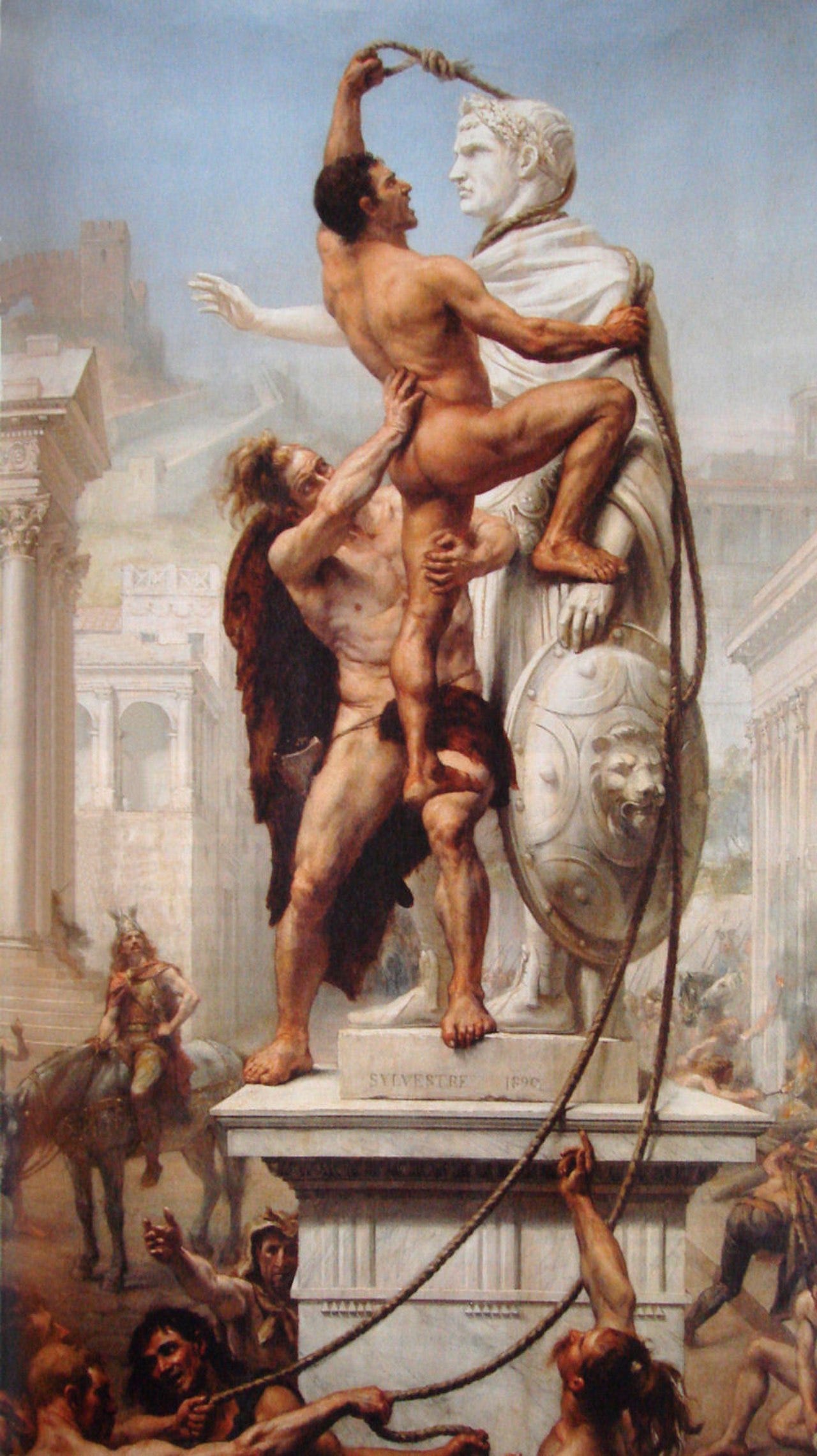

The end of Empire

All good things come to an end. But boy what a grand celebration it was. It was a baccanalian celebration at the ludi saeculares, the century games in Rome, on 21st April in AD 248. It marked the thousand years of the Roman Empire.

An exotic menagerie befitting the seat of a tricontinental empire was presented to the people, and massacred: thirty-two elephants, ten elk, ten tigers, sixty lions, thirty leopards, six hippopotamui, ten giraffes, the odd rhinoceros, and innumerable other wild beasts, not to mention one thousand pairs of gladiators.

Kyle Harper (2016) quoting the words of Edward Gibbon in his tome the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire

No one knew that it would be their last.

![[A Compleat History of Druggs ... The second edition.] [A Compleat History of Druggs ... The second edition.]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!mFgM!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F5cc9711a-587b-4d93-a1ad-827d0d4c8a52_792x1024.jpeg)

Context

The decline and fall of the Roman Empire (beginning around AD 410) ushered in the Middle Ages in Western Europe. Graeber’s interest lies in countering a common assumption that with the downfall came the loss of money and coinage. The common assumption was the regression to the barter system.

Graeber disagrees. He would vehemently disprove this.

The Middle Ages is commonly thought of as the Dark Ages. Not quite, says Graeber. It was the time when

the coinage-military-slavery complex ceased

the virtual credit money (with the decline of coin usage) dominated

predatory lending declined with the rise of the religious orders

Let’s expand some of his evidence for Western Europe.

The military decline

We cannot fully ascertain the multitude of factors that led to the replacement of the Roman Empire into multiple entities commonly labeled as the Barbarians. The Visigoths in Spain, the Anglo Saxon in Britain, Goths and Lombards in Italy, Franks and Burgundians in France, and the Vandals of North Africa — all of them occupied the vacuum of the post-Empire.

What happened?

The might of the Roman empire lies in its military leader, its armies and the vast logistics that support it. Slowly, the expanse of its five million square kilometers stretching across Africa and Asia, chipped away at its edges. The weakening of the frontier is what led to its eventual demise. How it happened is debated.

Albert Ferrill points to the changes that weakened the Roman military prior to its collapse. From around 200,000 men in the army, it would cease to exist by about AD 475.

Emperor Constantine (AD 306 - 337) embarked on a ‘central mobile striking force’ (Feldheer or Bewegungsheer in German; armée de manouvre or armée de campagne in French) that removed forces at the frontier (limes) into the centre that did not really need the auxilliary forces protection

Corollary to this is the military strategy of defense-in-depth, in which walled defenses are not impregnable except for a fortification that can withstand attacks (siege warfare) and allow the mobile army to engage in war; this strategy created a two-tiered army structure—a highly trained elite force who does the fighting and a sub-par untrained frontier infantry men that led to demoralisation in the ranks

The integration of barbarian as soldiers and allies (contentious) led to further demoralisation of the Roman soldiers because they saw preferential treatment (less taxes and leniency)

Several battle defeats eventually led to the sacking of Rome several times prior to the last emperor at around AD 476.

The decline of coinage use

The breakup of the empire into various smaller kingdoms did not necessarily led to the disuse of coinage. Different kingdoms decided on different ways to handle the former Roman practice.

According to Mark Blackburn,

Britain stopped the use of coinage after the Romans left in AD 410 when importation of the coins ceased. Any existing coins were used as ritual ornaments or grave goods. They would not have any full scale minting until the seventh century.

Among the Gaul and in the Iberian peninsula, there was a shortage of silver and bronze. The coins that were minted imitated the previous imperial coins rather than their own image.

In Italy and North Africa, the succeeding officer/ruler, Odocavar (AD 476- 493) from the eastern empire, followed the minting of his imperial predecessors, Julius Nepos (Western Empire AD 474 - 475) and Zeno (Eastern Empire AD 474 - 491). He continued the minting of coins with centres in Rome, Ravenna and Milan.

With the breakup of the large army, there was hardly any need for coins to pay to soldiers. Here, Graeber’s argument about the link between armies and coin use is supported. More interestingly, the new conquerors did not see any use for these coins in any of their transactions. Moreover, those that did use it imitated the image of previous imperial consuls, and their worth, rather than themselves. Coins became too expensive to produce and without the autocratic might to mine exclusively for minting, it makes sense to see it as a highly inconvenient and expensive activity.

There was hardly any record of what type of credit system or arrangement was in place. More information would surface around AD 800.

The state of slavery

Graeber attests that slavery would reduce significantly with the absence of the military coinage complex. There is little information that speaks to the slavery in the mines during that period. However, I looked at the rural economy for clues into any payment arrangements and labour relations in place.

The barbarian conquest belies the fact that barbarian immigrants into the Roman empire was highly desirable. A recent analysis by Sebastian Schmidt-Hofner shows that there was a legal precedent to tie people to land: ‘the bound colonate.’

[…] Therefore, we grant to all persons the opportunity to supply their private possessions with men of the aforementioned group. And all persons shall know that they shall hold those whom they have received by no other title than that of the colonate (ius colonatus), and that no one shall be permitted either fraudulently to take anyone of this group of coloni away from the person to whom he had once been assigned by deceit or to receive such an individual as a fugitive, under the penalty which is inflicted upon those who harbor persons that are registered in the tax rolls of others (censibus adscriptus) or coloni who are not their own. (§1). Moreover, the landowners may use the labor of these captives like that of free persons (opera autem eorum […] libera utantur) [lacuna]; and no one shall be permitted to transfer such persons, as though they had been given to him as a present, from the obligations of the tax rolls (a iure census) to that of slavery, or to assign them to urban service (sc. as domestic slaves).

Emperor Theodosius II (AD 408-450), ruler of the Eastern Roman Empire

The colonatus or colonus appear to be the social and legal statuses to keep individuals as agrarian labour for the land owners.1

the coloni were effectively stable taxpayers in the empire

the coloni were banned from army conscription

This status also covered barbarian immigrants during the fourth century when competition among the landowners necessitated more agrarian labour. Schmidt-Hofner still found evidence for a slave society using war slaves for the fields. The status of coloni remains limited.

Though some immigrants were granted tributari status, the term itself does not imply freeholding or one that pays tax on the land use. Rather the term is synonymous to dependent farmers like the coloni. Changes will occur much later than this early period of transition.

Round-Up

Graeber opens the Middle Ages with a positive observation: the dismantling of the military-coinage-slavery complex. I wanted to briefly look at the case at the end of the Roman Empire (AD 476) and the barbarian conquest that carved up Pax Romana.

Scholar Andrew Ferrill approaches the question of decline through a military lens. He identifies three reasons how a 200,000 strong army suddenly ceases to exist less than eighty years later.

The decline of the Roman Empire is closely linked to the decline of the military society.

Following the changes to its military strategy in the frontier, the creation of a two-tiered army of fighters and expendables led to demoralisation and weakening of the army machine.

The inclusion of barbarians into the army and allies. The two-tiered treatment between Roman soldiers and its counterparts (no taxation and leniency) led to demoralisation.

The political and military destruction of the Roman Empire accompanied the decline in coin use by the succeeding barbarian kingdoms. There is no record yet of what was in use. However, this supports Graeber’s thesis that the decline in war, also means the decline in coin use and the increase in credit arrangements.

However, the decline of slavery does not apply yet. Roman society is still a slave society especially in farming. Despite the category of the coloni, a dependent taxpayer farmer, the conditions still remained slave-like. Perhaps, any changes that supports Graeber’s observation occur several centuries after.

Re-read the previous post

Chapter 9 (Part 5): The Axial Age (453-221 BC)- Materialism II: Substance

Graeber argues for the materialist turn in philosophy as a result of the coinage-military-slavery complex of the Axial Age

Though they may be tied to one landowner and land, they were frequently absconding to work on another land to extract better benefits from the second landowner. Landowners welcomed what in essence is free labour because they are benefitting from the ghost worker leaving the first landowner to shoulder taxes and other obligations.