Chapter 10 (Part 2): Ashoka's Age (265-238 BC) and Buddhist Expansion (450 BC- AD 1200)

The foundation of the first banks in India is through Ashoka's conversion. Charity and commerce together would become the medieval age.

If you are new here, we are reading David Graeber’s Debt: The First 5,000 Years. Catch up and join us on Thursdays in 2024. My first slow read here on Substack in 2023 was David Graeber’s The Dawn of Everything. These two books showcase his thesis on the development of humanity by looking at how debt evolved and how people organised themselves and their world. Unique among his peers, Graeber still asks the big questions in anthropology.

Dear Reader,

I have fallen ill upon my return but nevertheless, I will try my best to continue our journey into the pre-medieval period.

But first, some food stories.

I’ve had my fill of exceptional fermented bread and pastries in Paris. It was not easy to find them. It required walking around new areas and orienting yourself to the city. Once you do, you will notice more gentrified coffee places and bakeries (usually run by younger entrepreneurs willing to buck the trend). One discovery just up the street from my bakery, Du Pain et des Idées, is the Brussels brand Buddy Buddy Nut Butter Café. I did not know that it was NOT a French brand at all. Apparently, it was to showcase their peanut butter first.

Now I regret ignoring their jars on display because I needed a good shot of strong coffee (which generally is on the weaker side in Paris). That shop has been embraced by young tourists and French people to the point that I will not recommend it during peak hours in the afternoon. It’s not a place to sit quietly and read (you will find yourself standing by the street or sidewalk and waiting 10 minutes for your order!) But for the caffeine fix, they have Amsterdam roasted beans so I am pretty sure you will get strong coffee here.

My strong espresso came with peanut goodness that I am willing to overlook the standing-room-only situation. I even went twice in a week! This is, of course, only good when you are on vacation. At 5.50 a cup, it’s not your neighbourhood Joe. Did I mention that everything seems to have gone up in Paris?

Now that I have relived the delicious memories, we can travel back to the dusty past.

Melanie

The discovery of Ashoka’s Edicts

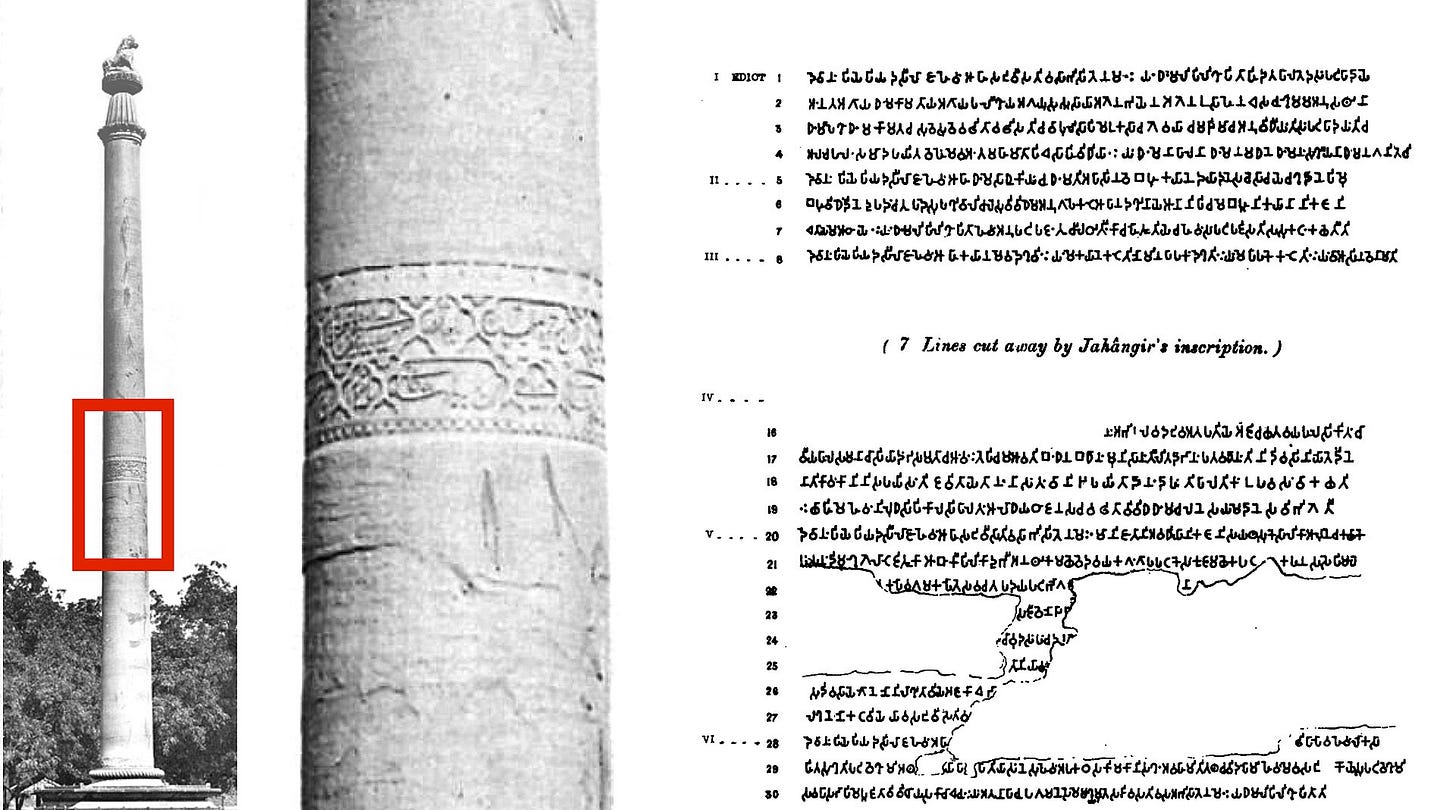

We last travelled to Bronze Age India during the time of Ashoka (265-238? BC), the last great military leader who united much of India until the Gupta Empire in AD 320-550. His legacy was forgotten and lost to history though his numerous pillars1 were found across his continental empire in India.

Much of the writing then was undeciphered until a colonial administrator and curious scientist, James Prinsep, felt compelled to salvage the decaying inscription on a neglected ruin. It was with the help of the engineer corps Captain Edward Smith who performed the task of reproducing the text.

To perform the operation in the most complete and engineer-like manner, Captain Smith divided off the written part of the column into six lengths, and each of these again longitudinally into four quadrantal subdivisions, so that the whole surface of the stone could be printed off upon twenty-four large sheets of paper or cloth. Each paper was made to extend somewhat beyond the actual limit of the compartment so as remove any uncertainty in regard to the letters near the edge.

James Princep reporting to the Royal Asiatic Society of Bengal, November 1837, p. 964

The copies were sent to Calcutta. Three were made. Two shipped, 790 kilometres away—one in paper and cloth. The third was kept as insurance in case of an accident. You can imagine the excitement of Princep upon receiving the rubbing.

Upon their arrival in Calcutta I lost no time in unfolding the roll and connecting the whole of the paper series (which seemed to have received the strongest print) into a continuous sheet, an operation rendered extremely easy by the tickets and directions accompanying them…When united together the lettered surface measures nearly thirty feet long by nine in width, and comprehends a written superficies of 160 square feet!

James Princep, p. 964

The task of comparative philology and Indology is complex and fascinating. Princep unlocked the forgotten Pali script2 to discover the term Devanampiyè Piyadasí (the beloved of the gods, Pidayasi) is none other than Ashoka.

The king’s conversion

As the Kalinga War ended in 261 BC, an invasion that Ashoka undertook for multiple reasons:

to punish the province as it broke away from control

to keep the waterway and coast clear for trade

to extract resources

The king was filled with abject horror and remorse for what he had done. We know of this dramatic reversal because he carved, not a confession, but a pathway to redemption in stone.

Beloved-of-the-Gods, King Piyadasi, conquered the Kalingas eight years after his coronation. One hundred and fifty thousand were deported, one hundred thousand were killed and many more died (from other causes). After the Kalingas had been conquered, Beloved-of-the-Gods came to feel a strong inclination towards the Dhamma, a love for the Dhamma and for instruction in Dhamma.

Now Beloved-of-the-Gods feels deep remorse for having conquered the Kalingas…Now it is conquest by Dhamma that Beloved-of-the-gods considers to be the best conquest…I have had this Dhamma edict written so that my sons and great-grandsons may not consider making new conquests, or that if military conquests are made, that they be done with forbearance and light punishment, or better still, that they consider making conquest by Dhamma only, for that bears fruit in this world and the next. May all their intense devotion be given to this which has a result in this world and the next.

selected excerpt from the Major Pillar Edict XVIII, From An English Rendering by Ven S. Dhammika

Though already a practitioner, the king, came to embrace the Buddhist practice and the call for peace fully. It is quite unlike the series of military conquests that characterised his rule (or his forbears). This complete turn established Buddhism as the official religion. Monasteries across the kingdom were built. The spread of Buddhism extended overseas all over Asia—China, extending to mainland Southeast Asia. Though Buddhism would be supplanted later by Hinduism and Islam, these early temple administrations created a robust system of credit and interest payments that lived long after the kingdom.

Unlocking Ashoka’s Mauryan kingdom’s writing showed the profound impact of his rule even as the kingdom ended around 185 BC. It would be the last time that India was united politically until the Gupta Empire.

Before we tackle the monasteries and debt that Graeber focused on, let’s look at the two other coinage-military-slavery trifecta at the end of the Mauryan Empire.

Coinage at the end of the empire

The grand project of political unification was short-lived. We can think of it as an exception to the rule. The default is political fragmentation. India, once again, is divided into multiple local kingdoms.

Coinage powered by a large centralised military machine ceased. But coinage itself did not disappear. Rather, its uses were merely redirected to other activities such as trading and minting at the local level.

Between 100 BC to 300 AD, trading was one of the centerpieces between the Roman Empire and India. Greek and Roman coins proliferate in the northwest of the country in contact with the Seleucid Empire3. The western and southern coastline is thriving with trade across the Red Sea to the Mediterranean and back. The gold and silver coins flowed from Rome to acquire luxury and exotic goods from India.

India has become the sink of the world’s precious metals.

Pliny the Elder, from William Darymple’s The Golden Road

One of the sources of the enormous amount of coinage in India was external trade. The local minting would be inspired by these Indo-Greek coins in its design and manufacturing.

The persistence of slavery

Slavery mining for precious metals to manufacture coins did not fully disappear. However, in this period, there are hardly any records apart from what was prescribed in the ancient book of Arthashastra (compiled and edited between 200 BC to 300 AD), on statecraft, where much information was reconstructed.

Despite this, a large swath of the military force would have returned to their agrarian tasks. According to historian Romila Thapar, the remaining administration was troubled with unproductive land and moved people to work on it. These were called the shudras who often were imported into the area to cultivate. There would also be the dasa-karmakara or the slaves and hired labourers who also worked the land. She also noted the persistent use of slaves in domestic homes of the upper castes, the mines, and some craft associations.

It is true that without a large military army like the Mauryans once had, credit arrangements become more prominent. But not without a curious incident in Indian history. The king’s conversion was critical as his peace adherence led to the creation and institutionalisation of Buddhist monasteries across India and overseas. Without the military expenditure, all the energy of the population went to agriculture and trade. Together, we see how charity and commerce intertwined forming the first banking practices of saving, lending, and extorting (or earning) interest (potentially at usurious levels).

Something we shall look more closely at next week.

Round-Up

To understand medieval India around 600AD – 1500AD, I wanted to understand how monasteries came to be India’s first bank. Thanks to the discovery of Ashoka’s edicts, we now know that his Buddhist adherence popularised and institutionalised the spread of Buddhism across all corners of his empire and abroad. Though his reign would end and ultimately be replaced by the Brahmins, the foundation was laid for the monasteries and caves to become the hotbed of financial activity.

We first needed to understand:

The conversion of King Ashoka to Buddhism led to the establishment of monasteries and the export of Buddhism to mainland Southeast Asia and China.

The military decline redirected human labour and resources towards the trading of rare goods between the Roman Empire with India.

Curiously, charity and commerce activities entwined to form the early banking systems that allowed merchants and other people to borrow capital.

It is not farfetched to see how this pattern also possibly influenced the way Christendom would hold wealth and power during the medieval age.

Re-read the previous post

Chapter 10: The Middle Ages (AD 600-1450)

The fall of the Roman Empire broke the military-coinage-slavery complex. What follows is a loose conglomeration of kingdoms with little use for coins.

According to Indian historian, Romila Thapar

“The edicts of the earlier half of his reign were inscribed on rock surfaces wherever these were conveniently located, and are therefore referred to as the Minor and Major Rock Edicts. These were distributed widely through-out the empire especially in areas of permanent settlement and concentrations of people. In the latter part of his reign his edicts were inscribed on well-polished sandstone monolithic pillars, each surmounted with a finely sculpted animal capital, and these have come to be known as the Pillar Edicts. The stone was quarried from sites at Chuñar near Varanasi and would have involved much technological expertise in cutting and engraving. The Pillar Edicts are confined to the Ganges Plain, probably because they were transported by river. The area coincides with the heartland of the empire.” (179)

The edicts were written in the local languages. Several of them were written in Aramaic and Greek for the northwestern audience of the kingdom. This greatly helped clarify the subsequent translations of the edicts.

After the death of Alexander the Great, the Eastern Empire was ruled by General Seleucid.