Addendum Chapter 10 (Part 5): For the Love of Cod—How Christian Fasting Created the Fish Market

Flesh days/fast days provided a Christian world order underpinned by fish

If you are new here, we are reading David Graeber’s Debt: The First 5,000 Years. Catch up and join us on Thursdays in 2025. My first slow read here on Substack in 2023 was David Graeber’s The Dawn of Everything. These two books showcase his thesis on the development of humanity by looking at how people organised themselves and their world around human values and choices. Unique among his peers, Graeber still asks the big questions in anthropology.

Dear Reader,

I couldn’t let go of this nugget of information I found doing the Hansa merchant chapter—stokvis and the Christian market it served. It is great timing that we are celebrating Christendom’s Lenten Season. It began yesterday, Ash Wednesday, the forty-day fasting period culminating in Easter.1

There is no one way to do the fasting. There are only levels to the rigidity of the requirements. Some take no food during the entire forty days following the steps of Jesus and the early Christians in the desert environment who went without food. According to contemporary Church Canon Law, meat is abstained from every Friday throughout the year. Typically, meat, most dairy products and eggs are avoided during the fasting period. Hence, the pancakes for Shrove Tuesday (or Fat Tuesday) use the last of the eggs and milk in the pantry! The carnival season (think, Mardi Gras and Rio’s Carnaval and the Dutch’s wild carnival weekend) is the final festivities before the sombre and bodily restrictions of the lenten season.

Fish replaced meat as the source of protein during the periods of abstinence and fasting. This drove the Baltic market for stokvis from Norway. This post follows the Hansa notation in Chapter 10 mentioning the commodities that were in demand following the Christian calendar and requirements.

Let’s jump right in!

Melanie

Stokvis as a Christian commodity

Stokvis or stockfish, air-dried unsalted cod, is now an expensive specialty good rather than a mainstream commodity. At least, everywhere else, its consumption is minimal—except for Nigeria, where almost 99.9% of Norwegian stockfish are sold (with the US and Italy on the list). During the late 1960s, the Biafran civil war in Nigeria caused famine and this prompted the donation of stockfish by Norway. It has since been incorporated as part of their local cuisine.

Unlike its southern counterpart, the Portuguese Bacalhao, Norwegian stockfish did not need salt. Salt was not in use until much later in the late 13th century when Hanseatic traders from Germany imported German salt into the Scandinavian region to cure herring.2 Therefore, this air-dried fish was an essential component of the Christian liturgical calendar of fasting. The fish kept for five to seven years.

Producers

The people from the Arctic Norwegian coastal towns have been catching and preserving cod during the Viking Age (AD 793-1066), but as a seasonal endeavour.

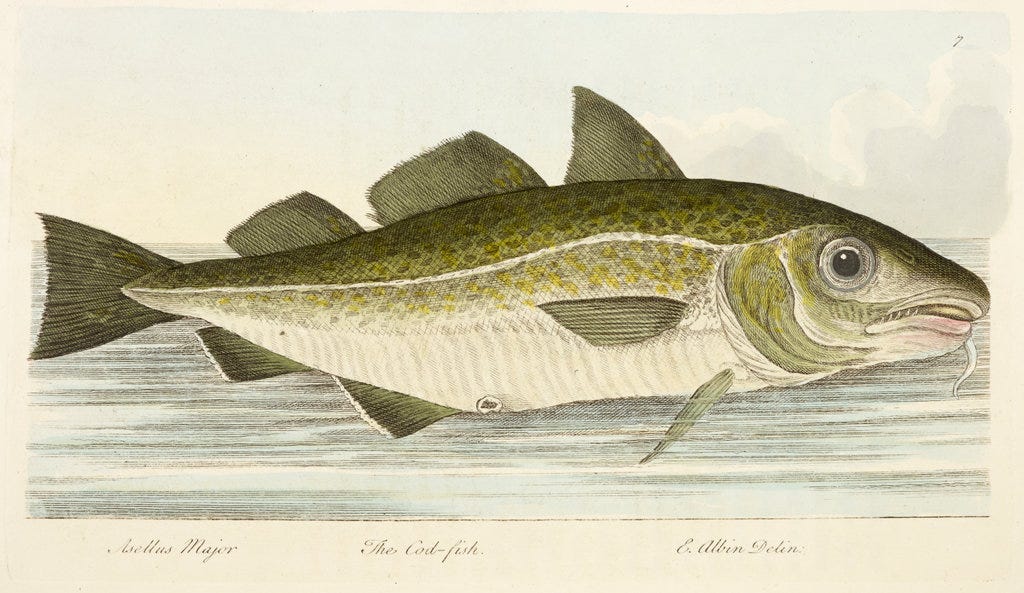

Cod (gadus morhua) can either be dried round with its vertebral column intact or flat with the vertebrae removed (called rotscher). Drying is done during the freezing months of January to April, which coincides with the spawning of the cod. Fish are caught and hung in drying racks for several weeks until fully dehydrated. To cook them, soak them in water, until it returns to its original form and volume.

According to Sophia Perdikaris et. al., the large-scale production of dried cod has been useful as currency for redistribution among the chiefly towns in Norway and to other Scandinavian social networks. Dried cod even reached as far as Iceland in the late 9th century. However, there are indications of a regional fish event horizon or a shift from subsistence to large scale commercial harvesting of cod and other fish products around AD 1000 (rounded off).3 Hence, this period coincides with the commercial revolution occurring in the medieval period.

Though the North supplied much of the stockfish, the southern port of Bergen is the main hub for export internationally. To undertake this trade, a northern social and trading network called bygdefar organises this undertaking. This network refers to a district in which skippers and farmers in the North charter a boat together to transport goods between Bergen and the other villages. The owner of the bygdefar or jektefart boat was usually a wealthy farmer. The relationship was governed by the so-called ‘jekte articles’ codified in 1739 in which skippers and farmers were contracted to help and crew the journeys. These are lifelong and hereditary contracts.

For those travelling to Lofoten, a crew consisted of 20-30 boat teams, a bygdefar contributed one man to each boat. For the longer trips to Bergen, each crew member was responsible for a certain number of the cargo on behalf of a farmer, including its sale, payment, and settlement.4

Merchant Middlemen

Finally, the bygdefar arrives in the port of Bergen. They park by the side of the wharf with the rowboats transporting stockfish off board. The return trip is stocked with much needed grain, beer, and cloth. The stockfish is ready to be shipped out by the bigger ships to England, Boston, Western Europe and Germany.

The price of stockfish dictated how much fish the fishermen/farmers produced. When the prices fell against grain, the Norlanders had to increase fish production as farming grain was very limited. Below gives you an idea of the prices back then. This is an example of a very simplified cost exchange between flour and stockfish with notes from Arnved Nedkvitne.

The price of stockfish depended on the demand from the Northern Europe markets. Nedkvitne points out two potential reasons for the decline in stockfish prices:

Norwegian historian Alf Kiil said that the Protestant Reformation eliminated the fasting period in the 16th century

Another historian, Schreiner argued that it was the competition from salted and dried cod from Newfoundland

Both probably had a hand in defining the tastes of the market.

Christian Consumers

There has been a debate whether the Christian lenten season indeed created a market or demand for fish or stockfish. No clear study or evidence yet can support this hypothesis. Poul Holm cites other social factors such as taste, cooking recipes, elite preferences, and gender roles may have played a greater role. Indeed, all of these shaped the market. I would add income, status, and location as coastal towns consumed fish and marine products before Christian conversion.

However, I argue that the religious aspect played a wider role in this market although it may be difficult to quantify. However, the Church's medieval liturgical calendar prescribed 132 days of fasting or abstaining from meat and meat product consumption. These days of obligation include:

every Friday of the year = 52 Fridays (from 52 weeks)

Lenten Season = 40 days of fasting until Easter celebrations

Ember Days5 = 12 days

Rogation Days6 = 4 days

Advent Fast7 = 24 days

The total for all five is 132 days.

This is not few considering German historian Wilhelm Abel in Nedkivte remarked that meat consumption was estimated to be more than 100 kilograms per head per year in Germany during the late Middle Ages. The elite even consumed more! (see Nedkvitne, 512) It is not surprising that art during that period provides a commentary against the seven deadly sins that include gluttony and greed.8

Such excess and the uncontrolled urges of the flesh are the goal of the periodic fasting regimen. Monks and nuns aspired to follow the early communities in Christ as an act of devotion but also mirrored the period of withdrawal, contemplation, temptation, and bodily suffering of Jesus of Nazareth in the desert (see Matthew 4:1-11 or Luke 4:1-13). This was important to achieve clarity before Jesus’ public ministry. St. Thomas Aquinas wrote his Summa Theologica from 1265 to 1274, expounding on the Christian theology and philosophy, including the virtues of fasting. For those outside of the monastery, fasting is an opportunity to participate in contemplative life in the everyday context.

…fasting loves not many words, deems wealth superfluous, scorns pride, commends humility, helps man to perceive what is frail and paltry.

from Augustine in St. Thomas Aquinas, Summa Theologica

Why Fish?

In his beautiful research on the medieval fish, The Catch, environmental historian Richard Hoffman adds three reasons how fish consumption shaped medieval European markets:

religious taboos

medical theory

public display of status

His social analysis provides us with a holistic picture beyond simply cost calculations.

Constructing the social fish

Curiously, Hoffman did not find any specific ideological prescription for Christians to eat fish. Rather, the avoidance of meat meant that religious culture encouraged fish. Mary Douglas’ Purity and Danger explained why the binary opposites of flesh days/fast days play into the predilection of human tendencies to think in dualities. For her, the contrasts provide order in our world.

Fish seems to fulfill the opposite of meat in that it was not quadrupeds, warm-blooded, possessed no feathers and glands to provide milk for the young. The medical theory classifies fish as cold and wet, appropriate to temper bodily heat and lust. Unsurprisingly, fishes are also graded by types. Oily coloured flesh fish like salmon and trout needed a sharp dressing such as pepper, but white dry meat just required a simple dressing.

Not all fish are the same.

The elites could afford to eat fresh fish found in their domain. These include eel, perch, trout, salmon, with pike and sturgeon occupying the top of the scale. These are commonly caught from fresh water sources and fish ponds. Monasteries have access to such fish and isotope samples from a selection of their skeletal remains, which confirm a predilection for fish. This meant that fish is an indicator of bounded status.

In northern Italy,…Lenten weddings at Piacenza followed a different festive custom keyed around fish. First on the menu came drinks and sweets, then figs and almonds, followed by a ‘large’ fish in pepper sauce. Next a spiced rice and almond milk soup with cured eel, and then fried pike in vinegar or mustard sauce, washed down with mulled wine. Nuts and fruits finished the repast.

p. 80-81 Hoffman

That sounds heavenly compared to ordinary folks who have to choose between eating herring or stockfish. An English textbook from the Middle Ages suggests to the reader,

…use the herring in the winter and save the stockfish for the spring, since stockfish kept better than herring.

p. 512 Nedkvitne

Fresh live fish cost more than dead ones.

This did not stop ordinary households from producing some tasty recipes reconstructed here.

Round-Up

Every medieval commodity has a story. Stockfish is one of several that is directly influenced by the Christian market. Prior to this, stockfish has been locally valued and redistributed among the chiefly communities in the area.

Our post today looked at the production, trade, and consumption of stockfish from Norway until the markets in Germany. The commercial switch is called the fish event horizon dating around AD 1000. This period transformed the North Sea and Baltic regions.

This was made possible with the innovation of the

Hansa clinker and Norwegian jekt for transport across the coastal region of Norway

the increase of traders coming into Norway

the valued exchange of grain, beer, and cloth in return for stockfish

I have framed my argument around fish demand with the Christian religious taboo of meat consumption during special days. Nevertheless, fish consumption is dictated also by culture, status, and health reasons.

Sources:

Barrett, James and David C. Orton (eds.) 2016. Cod and Herring: The Archaeology and History of Medieval Sea Fishing. Oxford: Oxbow Books

Hoffmann, Richard C. 2023. The Catch: An Environmental History of Medieval European Fisheries. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Nedkvitne, Arnved. 2014. The German Hansa and Bergen 1100-1600. Koln: Bohlau Verlag GmbH

Sicking, Louis and Darlene Abreu-Ferreira (eds.) 2009. Beyond the Catch: Fisheries of the North Atlantic, the North Sea, and the Baltic, 900-1850. Leiden: Brill

Find your way around: the book outline

Re-read the previous post:

Addendum Chapter 10 (Part 4): Crusading and Redemption

The crusades were a costly Christian debt repayment plan during the medieval period

I have to be mindful of the liturgical calendar as the Catholic mass (Novus Ordo or New Order enacted since 1952) seemingly did not prepare me for this season. This was not the same for our medieval brethren who celebrated the Vetus Ordo or the Tridentine Latin Mass codified in 1570 in Trent, Italy by Pope Pius V. The pre-Vatican II reforms were more strict and rigid than what we have today.

Sea salt production in Scandinavia is limited by its cold climate, preventing easy evaporation. Brine is a likely candidate but unhelpful for stockfish. Rock salt may also be obtained through rock mining, but it appears that production is limited to only artesenal level if at all in Germany, Poland and Romania. (See Anthony Harding’s Salt: White Gold in Europe) Though German merchants acquired mined salt.

This term was coined by J.H. Barret and his team who dated the origin and spread of marine consumption around AD 950-1050 in the inland parts of Britain. This also coincided with other areas like the Faroe Islands, Scotland, Iceland, Northern Norway, but not Greenland. Some indicators found in the archaeofauna and archaeological evidence include:

shift from a multi-species to a monospecies selection for cod

specific fish butchery practices such as discarding of the jaw

appearance of sizing selection based on the jaw sizes

abundance of thoracic and caudal (tail end) vertebrae on site, that can determine the fish preparation (flat or round), and therefore ready for export

seasonal to permanent settlements in Lofoten and other islands (see Wickler)

imported products such as spindle whorl, flint for striking, bakestone or a flat rock measuring 25-50cm for frying or baking bread in an open pit in the Norwegian islands (see Wickler)

These factors roughly confirm Barret’s timeline of AD 1000 as a turning point in commercial fishing and exports in the Baltic Region and beyond.

This trading voyage is called the stevner from the Old Norse word stefna, meaning meeting. This route is considered important despite its distance.

These coincide with the change of the seasons with the prescription of three days of prayer, fasting and almsgiving set aside four times a year - Wednesday, Friday, Saturday preceding the:

First Sunday of Lent (spring),

Pentecost (summer)

Feast of the Holy Cross (September 14) (autumn)

Feast of St. Lucy (December 13) (winter)

These include the three days of special prayer and fasting preceding the Ascension Thursday (Minor Rogation Days). April 25th is designated as the Major Rogation Day dedicated to the prayer for the protection of crops and fields. Rogation comes from the Latin word rogare meaning to ask. It is traced to the 5th century Gaul ritual praying for rich harvests and protection from natural disasters.

An Advent fast is observed for four Sundays before Christmas or until Christmas Eve.

The others are pride, greed, lust, envy, wrath, and sloth.