Addendum Chapter 10 (Part 3): The Temporal and Spiritual Exchange in the Hanseatic Network

The commerce of the Hansa merchants overshadows the spiritual work of debt cancellation with God

If you are new here, we are reading David Graeber’s Debt: The First 5,000 Years. Catch up and join us on Thursdays in 2025. My first slow read here on Substack in 2023 was David Graeber’s The Dawn of Everything. These two books showcase his thesis on the development of humanity by looking at how debt evolved and how people organised themselves and their world. Unique among his peers, Graeber still asks the big questions in anthropology.

Dear Reader,

I had not started the sourdough project but I successfully finished the last of my one-litre yoghurt! I just made chocolate yoghurt cake! The good news is that it came up light and moist. Since I added about 1/4 cup of coffee, one cup of sugar did not make it sweet. So this recipe is a keeper for a quick chocolate fix. I’ve been making yoghurt cakes continuously now so I am happy to incorporate this variation as part of my muscle memory. This is the plan to minimise supermarket snacks while writing!

If you just jumped into Graeber’s book, we are still in Chapter 10 on the Middle Ages. The subsection we are discussing is the rise in European merchant capitalism and its ties to the church.

I am debating whether to go further into the fish commodity market or jumping right into the trader/crusaders in the next post. I am discovering so many great stories I had no idea about. There’s a lot of historical documents emerging and are now available for this period.

The lost and unopened letters from Antwerp captured by the hanse before it arrived in London in July 1533 can be read here. Tales of families, products sold and a lot of nitty gritty of life in Old English. Plus, the raw databases used by Sheilagh Ogilvie in her research on guilds is available for analysis! I hope this will be of use to someone.

Have fun,

Melanie

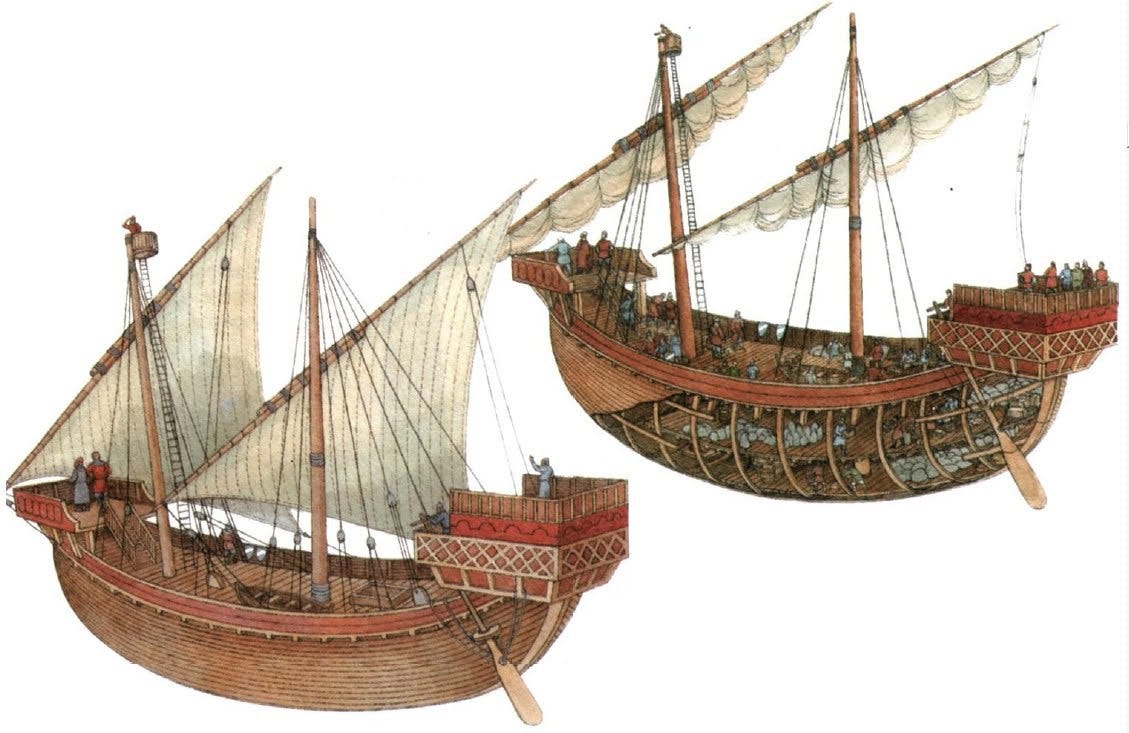

The Hanseatic Merchants in the Baltic Sea

Like their Italian counterparts, they are part warriors and merchants treading the dangerous seas for access to markets and goods. Unlike the Italian city-states, the Hanse merchants are amorphous, unincorporated, and are not necessarily guilds (although they may behave like one in some aspects).

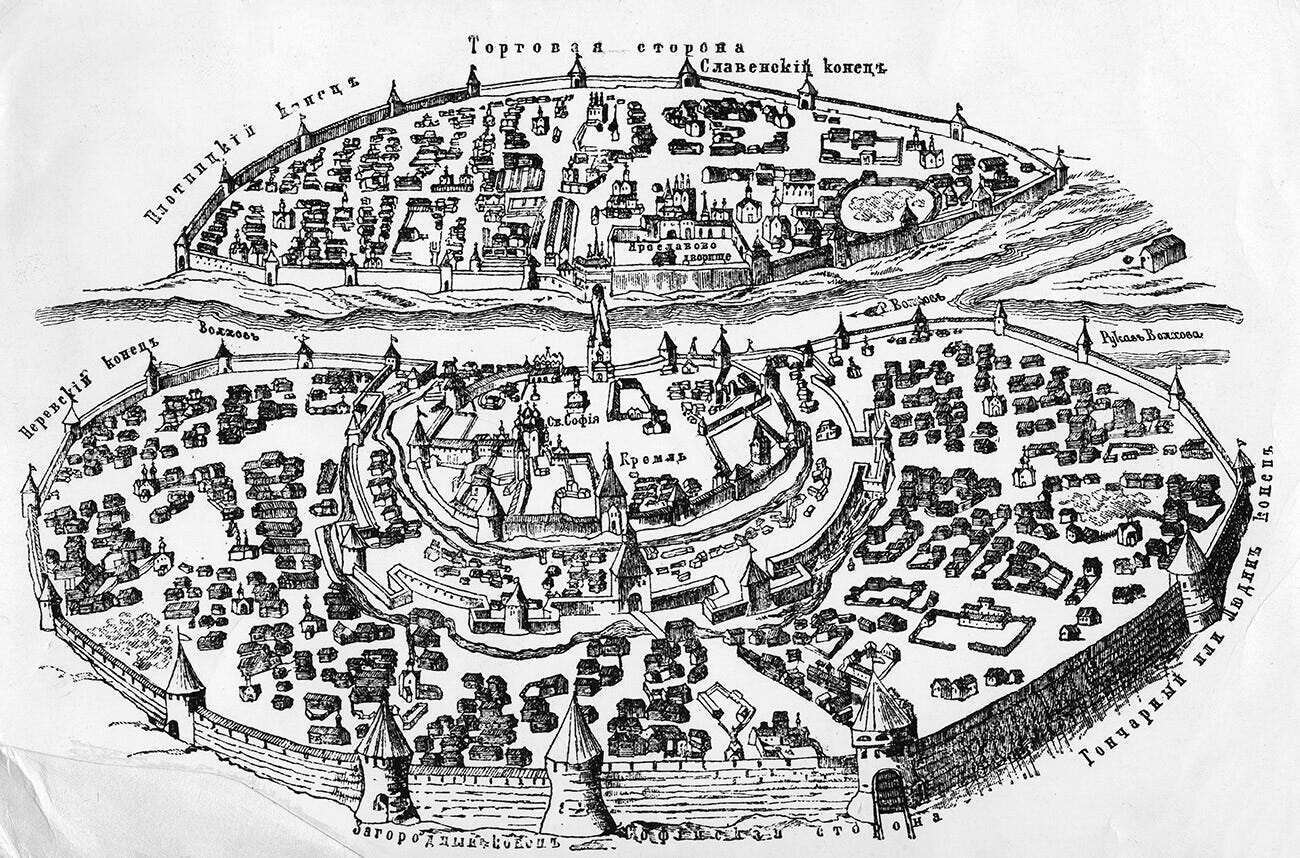

Lower German-speaking merchants from Lübeck (and other northern German towns) wanted to expand their trade into Novgorod (St. Petersburg). Thus, they negotiated with Gotlanders and established Visby as an important way station. The beeswax from Novgorod was an essential commodity to make candles for churches and monasteries in Germany.

From the West (North Sea Region), these merchants brought stockfish (cold air-dried cod) from Bergen, Norway eastward for the weekly fasting and meat consumption prohibition on Fridays in the Catholic tenet. At the hanse’s peak, they established their textile trading in London and Brugge.

Interestingly, these German merchants hardly used the bills of exchange that were more common in the Mediterranean and Western Europe centred in the seasonal trade fairs at Champagne in France. The problem with this system is that if there was an imbalance between any two cities, this needed to be settled in gold or silver buillion. Sometimes it was cheaper to transport buillion than to buy a bill of exchange.

Coinage appeared to be the dominant form of payment. The City of Schleswig, located in the peninsula straddling between the Baltic and North Sea, was an important coin emporium. It was where coins from the West were converted into the weight-money economy prevalent in the Baltic Region. This is a practice in which valuable metals in coins, such as silver or gold, are weighed to determine its value rather than the coin itself.

Coins in archaeological finds are clues to the lines of the network.

Cologne and Frankish coins are common in Danish and Swedish territories which arrived by boat from the Rhine River and North Sea

Frisian coins are common in Novgorod (St. Petersburg) which probably entered by way of the Swedish coast, Aland Islands, the Gulf of Finland to Neva River before reaching Russia

Italian and local Western Slavic coins entered the coastal region via land from Lower Saxon merchants

Since the region is vast with multiple cities and players, the story of the Hansa network can only be told at the local, individual merchant, or commodity level.

I can only discuss a snapshot of a highly dynamic trading regime.

Listen to more stories from this wonderful resource! Episode 120 - Money, Money, Money • History of the Germans Podcast

Early Hansa entrepreneurs: credit and trust

Much like the Italians, trade was a risky and dangerous affair, especially for long distances in the Baltic Region. Hence, merchants usually formed associations to de-risk and manage their peers. It was common to have associations based on the hometown or to their trade destinations. These groups are both for social and religious purposes but also a way to establish joint trading relationships. It is not surprising that these pre-date what would later be recognised as the hanse.

Rolf Hammel-Kiesow emphasised the autonomous character, called the kore or the law of self-governance of these voluntary associations. He accorded this as a core value, the ius mercatorum, the rights of the merchants to band freely in the rural communities that accelerated during the urbanisation shift in the eleventh century. This allowed for political and economic sovereignity.

What is a hanse?

The term hanse in the early Middle Ages means group/crowd (Latin cohors). The travelling association was called hansen in Western Europe. However, there are multiple legal and occupational meanings associated with this word.

a fee collected for participating in a joint trading relationship likely traced to manorial or royal tribute

the right to trade jointly

Its first reference came from the Valencienne merchant guild in northern France whose statute barred them from trading with a hanseur (a foreign and travelling merchant). This exclusion indicated that they were barred from becoming members of the guild and the general distrust towards travelling merchants.

It is commonly associated with merchants under the regnum Teutonicum (Holy Roman Empire of the Frankish Kingdom) in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries who fell under the king’s protection. However, their principle of autonomy meant that no clear oaths to other guilds or travelling groups were to be found.1 This is why the term is quite amorphous and flexible.

However, the manifestation of these hanse differed in their local contexts.

In the Baltic region, early hanse were collections of merchants at their trading destinations. For example, universitas mercatorum Romani imperii Gotlandiam frequentantium (the association of merchants from the Roman Empire visiting Gotland) are composed of companies or individuals sailing from Lubeck to Gotland, who would then later sail to Novgorod and Riga.

In Novgorod, a fortified settlement with St. Olaf’s Church as the centre was where hanse merchants lived and switched according to seasons. This prevented any long-term relationships from forming that disadvantaged the hometown traders.

How did it work?

The structure follows the pattern of what we have seen in the joint trading in the Genoan context. The collective trading in the late twelfth to mid-thirteenth centuries is called a wedderlegghinge or a pooling of capital. This is an arrangement of 1:2 or 2:1 investment of capital between two individuals. The individual with the smaller investment proceeded with the overseas trade. Profits and losses were shared with no specified terms. It is unclear whether these were company trades or under a commission arrangement. In Nordic records, such arrangements were called the felag in which the investors travelled together or alone. Hanse and other similar arrangements seemed to be an independent development across cultures.

The advantages of the hanse were the result of the exclusion and elimination of its competitors. It allowed for

monopoly of bulk purchases to meet a strong demand

a unified supply chain between buyers and sellers linking the sea and land trade

warehousing and storage options for goods

political and economic privileges that includes near monopoloy of trade in commodities, reduction of taxes and duties

political and economic independence with the right to punish their members and settle conflict among themselves

The network generally operates with

a principal merchant who was financing the trade located at the hometown

the carriers who transported the goods to the target location

a factor who resided abroad or the trading destination

The hanse usually assigned a unique partner for every trade rather than use a factor. This allowed the merchant to have an overview of each trade he made personally usually a family relation.

Given that there is no formal structure, oaths, or paperwork representing a specific hanse, these transactions of trust are made from the associations from the homeland or in trade destinations.

Commerce and Conversion: Paying an Unpayable Debt

The expansion into the Baltic Region commercially coincided with the mission of the Catholic Church into the southern and eastern Baltic Regions. Thus, it extended European Christianity by speakers of Germanic languages from Germany and Scandinavia in what was seen as a frontier area between AD 1000 to 1500.2 The Baltic region or Old Livonia was occupied by Estonians, Livs and Kurs (Curonians) who spoke Finno-Ugric languages and Lettgallians, Semgallians, and Selonians who spoke Baltic languages. The contact between these two groups has been an ongoing tale of raids and destruction on both directions.3

I am reframing these wars and contact in the language of debt. That is, the work (or payment) is twofold:

conversion saves souls (work of the clergy)

crusade absolves sins (work of the faithful)

The work of conversion in Livonia

Old Livonia (present day parts of Estonia and Latvia) was not only a trading entrepot but a land of that needed conversion. It was originally undertaken by the Danish kings and the archbishop of Lund (see footnote 3) but was actively inherited by Hartwig II, the archbishop of Hamburg-Bremen (AD 1185-1190/92, AD 1194-1207) when he consecrated Meinhard (AD 1185-1196) as bishop of Üxküll, a place yet to be visited and Christianised.

With no military power on hand, he was dependent on the merchants who entered the Düna river (a tributary that leads to the Riga in what is now Latvia). His missionary work as well as his successor, Berthold (d. AD 1198), resulted in few conversions. Berthold was to die by the hands of the local Livs in AD 1198. It was the third bishop, Albert von Buxhövden, who would successfully convert the area by force. According to the Henry of Livonia source text, he gathered armed crusaders in Lübeck and

in the spring of 1200…arrived with twenty-three merchant ships at the mouth of the Düna River.

from The Incorporation of the Northern Baltic Lands, by Tiina Kala p. 8

He later founded the town of Riga, which became a Bishopric.

By 1202, Dietrich4, one of the missionaries of then first bishop Meinhard, established the Order of the Sword of Brothers (Latin Fratres militiae Christi; German Schwertbrüder) which became one of the primary military force in the region.

Faithful work: crusading from Lübeck

Since then, the Order of the Swords of Brothers waged campaigns of conversion in the region. The jump off point of this army was from Lübeck. It was the main port of supplies and personnel to protect the Bishopry of Riga. However, in 1234 the port of Lübeck was under a blockade by King Waldemar II of Denmark. Since the mission to Livonia was part of the official papal policy, Pope Gregor IX forced the King to capitulate by threatening to use the crusaders to wage war against him.

Together, Bishop Albert along with help of Valdemar II of Denmark (who also had his own agenda of forming a rival to Riga) attacked Livonia.

In 1219, Valdemar II landed on the northern coast of Estonia. His forces have been estimated at 1000-3000 men and 100 ships, which represented approximately one-tenth of the sea-power at the time.

from The Incorporation of the Northern Baltic Lands, by Tiina Kala pp. 9-10

It was not the first time that the Danes and Livonians met. The latter destroyed Blekinge, a town owned by the Danes (see footnote 3). Estonia fell after the battle of Fellin in 1217. The Livs by 1206 having been forcibly baptised by the bishop of Riga. The other tribes succumbed by 1227 and the transformation of the Livonian landscape begins.5

The Pope mediated the quarrels over territorial disputes between the Order and the Bishopry of Riga. He awarded the Order with one third of the conquered lands.

Church indulgences: cancelling debts

What was in it for the merchants who willingly transported the clergy? Why join and risk your life for the Baltic crusades?

On the surface, the hanse city of Lübeck acquired additional papal privileges that shored itself agains the waning imperial protection of the city. However, the answers to these two questions involve the opportunity to pay an unpayable debt through—indulgences.

Church indulgences is akin to the burning of the promissory note. It promises absolution of sins by the pope, the vicar of Christ on earth. In the early formulary of the concept of indulgences, the crusades were akin to pilgrims. They were granted protection by the Church including their families and properties. As penitents, they were granted full remission of all sins by their action. This is called a plenary indulgence.

Eugenius III (AD 1145-1181) broke from this prescription and argued that there was no action that could satisfy God for sin. Successors disagreed with this position. They reverted to the original prescription that the pope could declare that a particular action would be regarded by God as satisfactory even if it is not. The participation in a crusade then was a satisfactory penance. The effectiveness of Innocent III’s call for the Baltic crusade proposed that the indulgence is a satisfactory act. It was a promise on God’s remission of the penalties of sin in purgatory.

The papacy of Innocent III (AD 1198-1216) issued a letter on December 29, 1215 that granted indulgences in the participation of crusades in the Baltic Region6 for those that could not go to the Holy Land ‘in remissionem peccatorum.’ This absolution also covers those who contributed financially ‘concessa eis qui subuenerint in personis aut rebus indulgentia peccatorum.’ Unlike the Holy Land mission, the absolution is only a partial indulgence. That is, the debt of sin is not fully erased. The distinction differs from those who took a vow compared to those who were about to join.

This recruitment incentive is highly regulated and hierarchical depending on the level of difficulty of the targets. The partial indulgence indicates a lower priority compared to the pilgrimage to Jerusalem. Nevertheless, we now understand two characteristic of Christian sin:

it can be repaid within a set period of time

it also cannot be fully repaid yet the amount can be reduced through ecclesiastical prescriptions

though we cannot pay our debt fully to God, his vicar on earth can grant clemency and absolution of sins (debt)

The Baltic crusade wars are an underrated series of events that implicate the hansa merchants, the Church, and the converted faithful in the work of debt payments.

Round-Up

The hanse league has two characteristics: a temporal and spiritual aspect under the aegis of trade and war. This post puts the two together to understand how commerce and Church intermingled in the European seas. Hanse merchants united the Baltic Region of East and Central Europe with the North Sea Region of Western Europe.

Hinterland commodities of furs, bees, beeswax move from Novgorod in Russia and Old Livonia westward. Beeswax is a critical item in church candles destined for Germany.

Sea products such as dried cod and salt move eastward to whet the appetite for fasting and land meat abstinence in the Christian weekly regime.

The early hanse is an informal and amorphous organisation that is described as a guild but without the institutional accoutrements that tie its members down. It is an association built on hometown roots but also located in trade destinations.

Like their Buddhist and Medieval Islam counterparts, religious conversion was part and parcel of commerce and settlement in these trading posts. With the interest of the papacy in the pagan Baltic region, crusading and its logistics were part of the hanse trade. The Baltic crusade is akin to commercial trade in which papal indulgences cancel the promissory note of sins for all participants. In this case, the partial remission of sins for the Baltic crusades show that:

Christian sin, though technically cannot be fully paid, can be repaid in increments or reduced given some amount of time and effort

the Pope, the vicar of the Church, can represent God who then can transform an irredeemable debt to full or partial payment

Sources:

Fonnesberg-Schmidt, Iben. 2007. The Popes and the Baltic Crusades 1147-1254. Leiden: Brill.

Hammel-Kiesow, Rolf. 2015. The Early Hansas. in Donald J. Harreld, ed. A Companion to the Hanseatic League. Leiden: Brill. pp. 15-63.

Kala, Tiina. 2001. The Incorporation of the Northern Baltic Lands into the Western Christian World. in Alan V. Murray, ed. Crusade and Conversion on the Baltic Frontier 1150-1500. London: Ashgate Publishing. pp. 3-20.

Spufford, Peter. 2002. Power and Profit: The Merchant in Medieval Europe. London: Thames and Hudson. pp. 34-38.

Urban, William. 2001. The Frontier Thesis and the Baltic Crusade. In Alan V. Murray, ed. Crusade and Conversion on the Baltic Frontier 1150-1500. London: Ashgate Publishing. pp. 45-74.

Wubs-Mrozewicz, Justyna. 2013. The Hanse in Medieval and Early Modern Europe: An Introduction. in Justyna Wubs-Mrozewicz and Stuart Jenks, eds. The Hanse in Medieval and Early Modern Europe. Leiden: Brill. pp. 1-25.

Find your way around: the book outline

Re-read the previous post:

Addendum Chapter 10: The Republic of St. Peter

The contours of the papal states resulted from defining which debt between material versus spiritual responsibility is more powerful

This is the principal characteristic of the hanse. The absence of clear markers of an organisation. No treasury, seal, oaths taken, or regular meetings held.

This was also the period in which the schism between the Western Roman church (Scandinavia) and the Eastern Christian Church (Russia and the Eastern Orthodoxy) was also vying for supremacy in the conversion process.

The earliest recorded was the Danes who conquered Rugen in 1169, the pagans attacked Oland in 1170 and the office of the archbishop of Lund between 1159-1201 planned twenty campaigns against the Slavic Wends who settled in the southern shores of the Baltic sea. These skirmishes continue with the destruction of Sigtuna, the commercial centre of medieval Sweden, in 1187 and Blekinge in southern Sweden by Estonians in 1203. I’ve classified this as part of the conversion and resistance in Old Livonia for Christianity.

He would later become the Bishop of Estonia in 1211. There is a debate whether Dietrich or Bishop Albert was the founder of the Order. More frequently, scholars name Albert as its founder.

From the point of view of the conquered, see Heiki Valk, Christianisation in Estonia: A Process of Dual-Faith and Syncretism

The earliest papal policy of crusading was from Eugenius III against the Slavs in 1147. The policy evolved from the pressure from the local ecclesiastical and secular leaders in the area. The papal monarchy in the thirteenth century was at its height and claimed divine and secular kingship in spiritual and especially temporal affairs.