Addendum (12.3): Haunted by Credit: 'Structural Adjustment' as Modern Tribute

Structural adjustment simply means, 'open your market for business' whether you like it or not

If you are new here, we are reading David Graeber’s Debt: The First 5,000 Years. Catch up and join us on Thursdays in 2025. My first slow read here on Substack in 2023 was David Graeber’s The Dawn of Everything. These two books showcase his thesis on the development of humanity by looking at how people organise themselves and their world around human values and choices. Unique among his peers, Graeber still asks the big questions in anthropology.

Bank Loans as Tribute

Graeber puts forward an interesting comparison between bank loans and the tributary nature of this debt relationship. Previously, we have defined a tribute as the mobilisation of surplus goods, which in turn, are goods or gifts used competitively to attain status or declare loyalty. On both sides, the parties involved negotiate more than a simple debit/credit relationship.

The U.S., wanting to promote free trade (break national protectionism) and avoid a catastrophic repeat of its own Great Depression, spearheaded the 1944 Bretton Woods Conference that gave birth to the International Monetary Fund (IMF). That meeting also negotiated for the U.S. dollar to be the global currency as long as it was backed by gold. Once this collapsed in 1971, the IMF had to evolve its mandate. Once an exclusive club that offered (cheap and emergency) credit to its rich members, it opened its doors to more and more low and middle-income countries.1 From what we have learned about the violence of unequal exchanges, the outcomes go beyond debt repayment. We see a modern-day debt peonage with deadly consequences.

The Credit Reckoning in the ‘80s

It was one big credit and trade party in the 1970s and the 1980s. The world was divided between communism and capitalism. It was not far to say that building democracy made the U.S./Central Intelligence Agency's political manipulation in countries nearly acceptable. Partly, it was to ensure they remain allies rather than turn Red—even if some of them ended up as unsavoury figures.

All this is a smokescreen for what is truly essential. All of these were for economic reasons. The U.S. needed new markets for their products and to eliminate the last of global economic protectionism. After all, during that time, the world was divided into the First World (led by the U.S.), the Second World (all the socialist countries and therefore, excluded from all trade), and everyone else in the Third World2 (Asia and Africa and all countries in-between). Half the world was open for trade.

At that time, the economic analysis could be simplified to a flow of raw materials from the South to the North. Non-industrial countries exported raw products and half-finished materials to developed countries, who in turn sell them back.3 Hence, the technocrats in government align with the goal of creditors like the IMF and World Bank to spur development. Their shared vision followed a linear development from non-industrial to industrial, from the Third to the First level.

It was supposed to work because the proof is the group of Newly Industrialising Countries (NICs), the Tigers of Asia—Taiwan, South Korea, Singapore, and Hong Kong. These countries focused on heavy to light industrial production in textiles and electronics that spurred growth and development. It showed that the linear growth towards industrialisation is possible for other countries to follow.

What critical analysts like Walden Bello and Robin Broad both argued was that these countries nurtured national protectionism and not total liberalisation. Those that did liberalise their economy never achieved this level of success.

The Philippines Experiment

It’s sexier to focus on the political reasons rather than the economic ones to explain the ongoing poverty and lack of development. Colonialism is an even easier reason to give, but without the economics, I will only be parroting the same framework for the Philippines’ current condition (typically attributed to failed state and cultural reasons). However, it is interesting to examine the financial cause that keeps the country under the heavy chains of debt.

The Philippines is one such country in a debt experiment. A former colony of the United States, it acquired the islands as part of the surrender of Spain in 1898 along with a payment of $20 million (approximately $775 million today) as compensation for infrastructure built and lost.4 The U.S. was an accidental coloniser and did not know what to do with it. What better way than for their colony to become another banana republic or a destination for American products, a source of raw materials, labour or the recipient of its greatest export—credit.

I can continue on this political development analysis. What is interesting and missed in most understanding of poverty is its financial causes. As Walden Bello argues in his work on the permanent crisis in the Philippines, the automated debt payment enacted into law, called the Automatic Appropriations, is the root cause.5 It is so minuscule, merely a phrase, found in the 1987 Administrative Code (Book VI, Section 26), which was a direct copy from the Presidential Decree 1177 (Section 31) promulgated on July 30, 1977 as part of the Budget Reform Decree of 1977.

Sec. 26. Automatic Appropriations—All expenditures for (1) personnel retirement premiums, government service insurance, and other similar fixed expenditures, (2) principal and interest on public debt, (3) national government guarantees of obligations which are drawn upon, are automatically appropriated: Provided, That no obligations shall be incurred or payments made from funds thus automatically appropriated except as issued in form of regular budgetary allotments.

Bold mine, from the 1987 Administrative Code and the PD 1177 Decree of 1977

If there is a forever war, it is notoriously linked to forever debt. And the Philippines has been paying since.

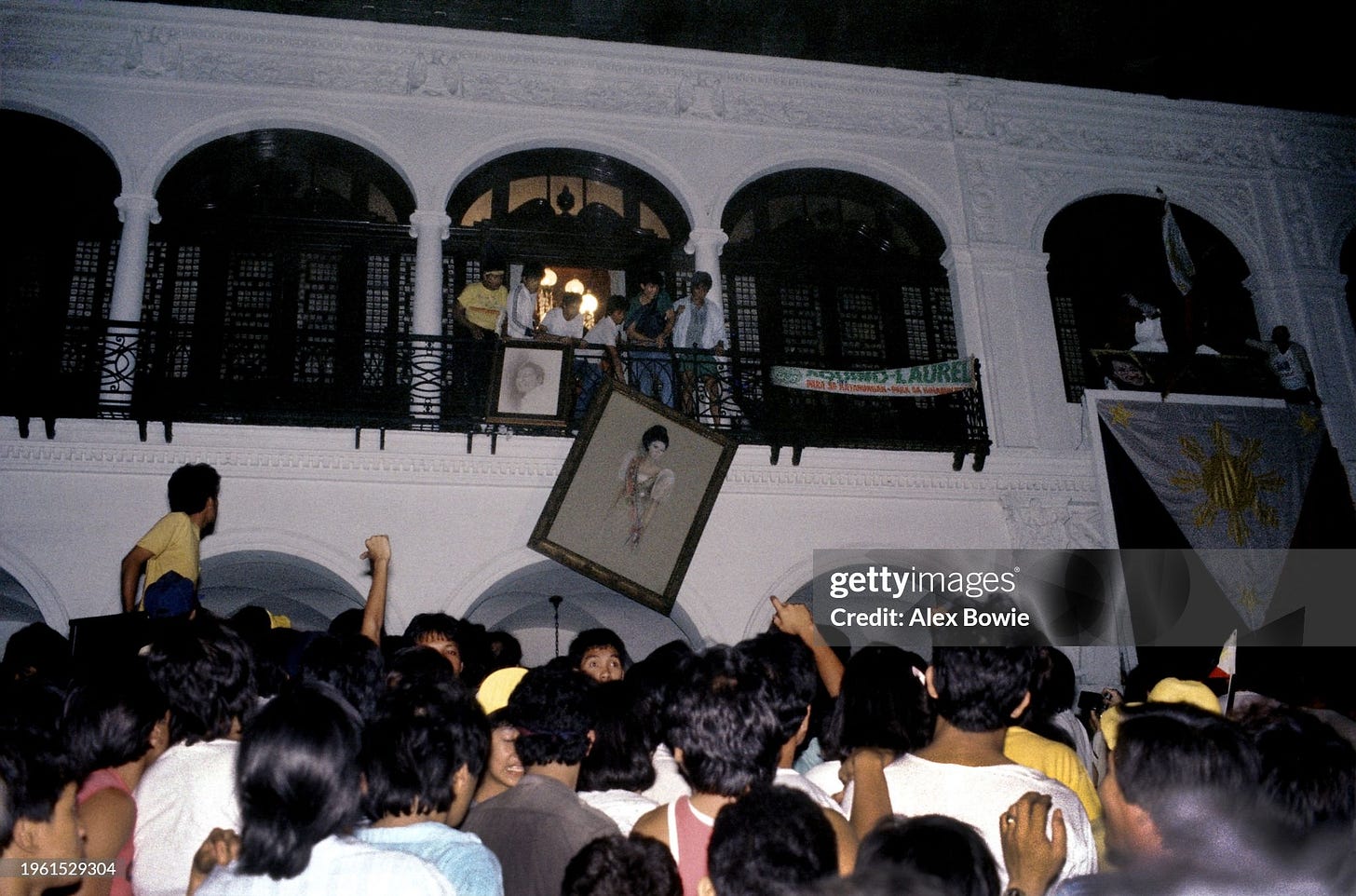

If you think that the difference is a mere ten years on paper (1977-1987), that decade encompassed the last eight years of a long twenty-year dictatorship by Ferdinand Marcos, Sr. He met his tumultuous end on February 25, 1986, with both a military coup and a civilian uprising called the EDSA Revolution.6

This political change should have delivered economic improvement. It didn’t. Despite the change in the Constitution preventing a long reign in office, its legal architects overlooked a harmless-looking clause. Thus, argued Bello, things got worse and continue to do so today.

The Philippine debt currently stands at PHP 16 trillion as of May 2024, and with the recent fluctuations in the currency, this will increase to PHP 17 trillion at the end of 2025. With the annual budget approved at PHP 6.3 trillion, debt servicing will be in the amount of PHP 877 billion or about 13% of the budget. It does not sound like a lot, considering that Public Works and Education remain on top, but this amount of money is what Bello says holds back social support and poverty alleviation. This could have been used to help a lot more people.

How did we get here?

Roots of Globalisation

Prior to the ascension of Marcos in 1965 for his first term, the Philippine economy was described as an import-substitution industrialisation economy. After World War II, the country had a healthy manufacturing sector that made up for the lack of imports in processed food, textiles and shoes. The government enacted import and foreign exchange controls, especially on non-essential goods, to prevent the drain on its forex reserves. This control spurred the growth in the manufacturing sector and accounted for 12% growth between the years 1950-1957. However, by the 1960s, this model was stagnating and in decline. There was little progress in manufacturing without the expensive importation of intermediate goods (steel, flour, fabric) and capital goods (machinery, computers, tools). The large transnational companies such as Procter & Gamble, Unilever, or Mead Johnson did not provide local investments, as most of their profit was remitted abroad.

In Robin Broad’s investigation, there was a protracted debate between export-oriented industrialisation and nationalist bureaucrats. Confidential documents of the World Bank (WB) and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) showed that there were ‘policy dialogues’ with bureaucrats. Broad tracked the capitulation of the staunch bureaucrats and the manufacturing elite to the first successful signing of a $200 million structural adjustment loan for the industry sector in September of 1980. What the IMF-WB did was pit the Ministry of Industry and Finance against the Central Bank, bypassing the latter to introduce currency devaluation measures, import liberalisation and tariff reduction policies.

This was the first among successive loans that forced the Philippines onto a terrifying tributary debt/development path.

‘Structural Adjustment’ is Suffering

What happened was an economic massacre of epic proportions to the local economy.

Tariffs were eliminated

Import restrictions were lifted

The currency was devalued

The domestic market is no longer the priority

The other light industries, such as textiles, cement, food processing, furniture and footwear, were targeted for restructuring

In other words, the ‘Made in the Philippines’ would no longer exist in its previous capacity. It would be as rare as a Made in the USA label. It decimated the shoe industry based in Marikina City.

There was only one shoe brand I would wear for school—Gregg’s. I disliked it so much because I simply rotated the classic brogue styles for me, and, oh boy, they would last like 5 years minimum. Technically, you could pass it down, but I was the youngest girl. My brother was saved from my hand-me-downs. You couldn’t destroy them if you wanted to. And I did, but no. I tried, but you’d only get a nail painfully poking your heel or sole. The parents will not take you shopping because you only do this once a year. All it needed, they say, was a sole or heel replacement by your neighbourhood shoemaker. I brought it to this shoemaker in a tiny cubicle at the mall in Greenhills. Under the light, it was satisfying to see him nail a new heel and shape the excess rubber with his small knife. Perfect. True enough, it was brand new again. The shoe will hold up for several more years. The thick leather will shine when you polish it. It only gets better with age. What a drag when you were a kid.

The annual trip is every summer before the school year starts in June, my parents will take us to Gregg’s shoe store in San Juan or to the shoe emporium that was located in Cubao. I had no choice but Gregg’s, but I secretly wanted a Hush Puppies. We spent half a Saturday or Sunday to find something that fit at the right price (i.e. cheap but sturdy enough). It was not easy to find one. But Gregg’s were handmade shoes for kids that were affordable. There is a perpetual call to revive the local shoe industry, but the economics are difficult when you can buy a pair from Temu for less than $10. Gregg’s has since shut, but the granddaughter of the owner, Lila Almario, might occasionally make shoes. I can only find eBay resale of her brand. The shoe industry resurrection remains a pipe dream.

My parents had a furniture business and we made hardwood and rattan cane furniture for the local market. (At least those who want high-end furniture in Louis XIV style or in any style they wish.) My parents ran a small factory with about 20 people or so who knew how to carve, sand, varnish, bend and put things together.

We also exported handicraft items elsewhere. Those baskets lining your flowerpot or ornamental decor that you see from China, used to be from different countries. We sent them to Canada and Japan. But we were at the mercy of the bank loan repayment, the OPEC cartel that drove oil prices up and down in the 80s, the protracted Iraq-Iran War, and the peso devaluation drove my parents to sleepless nights wondering if we could even break even and pay the workers.

It was not easy to run the furniture business. Hardwood and logging were banned in the 1990s due to deforestation. Fair enough. So all hardwood was being sourced out of Indonesia now. It was tough sourcing the raw materials, although rattan cane was still accessible. The business wound down in the late 90s. The local market was flooded with particleboard furniture, steel furniture (my cousin still makes them!) and basically cheap assembly furniture. The modernist and classical styles were out. My parents were probably relieved to end it by the 2000s. We were somehow lucky to survive and thrive, but ‘structural adjustment’ de-skills the workforce and eliminates jobs.

I wonder what has happened to all the skilled carvers and shoemakers we had.

I want to end with how ‘structural adjustment’ is the unspoken tribute extraction at the end of the credit line. It was not enough to lend money, but these loans come with stipulations to change the political/economic system that serves to embed and create parasitic ties that no one body can survive without.

The World Bank 1980 was the first tranche of loans that ensnared the Philippines in an export model that was quickly untenable as soon as the country was liberalised. The Philippines never truly industrialised and our labour costs were so high compared to our neighbours. It made perfect sense for President Marcos to facilitate overseas migration with Executive Order 797. The oil boom saw a lot of male Filipinos head to Saudi Arabia when construction was booming and they needed engineers and workers. The females headed to Hong Kong and Singapore to become domestic workers. The dollar remittances kept our country and dollar reserves afloat. Human (free labour) for credit repayments. This is the true tribute payment.

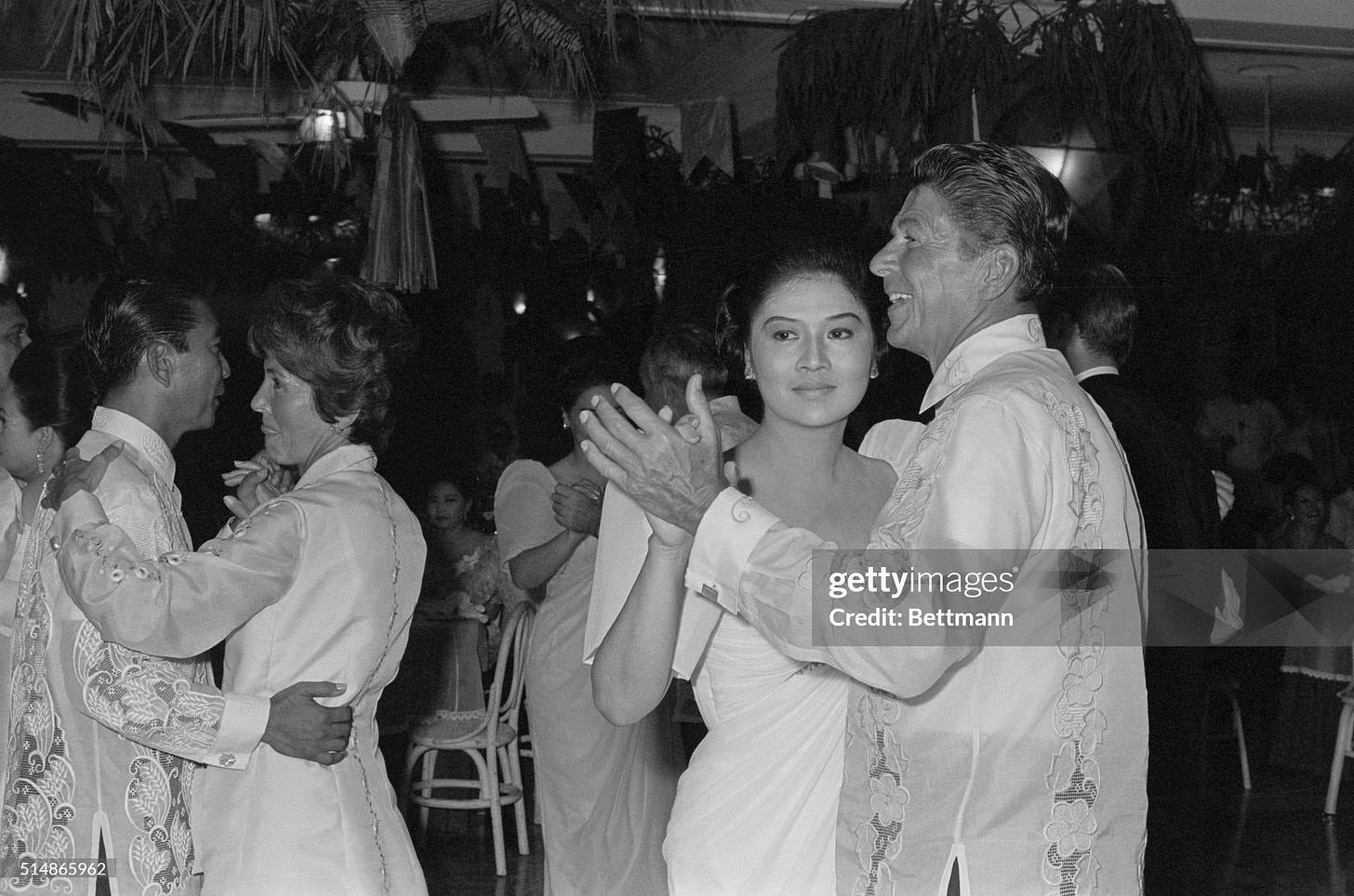

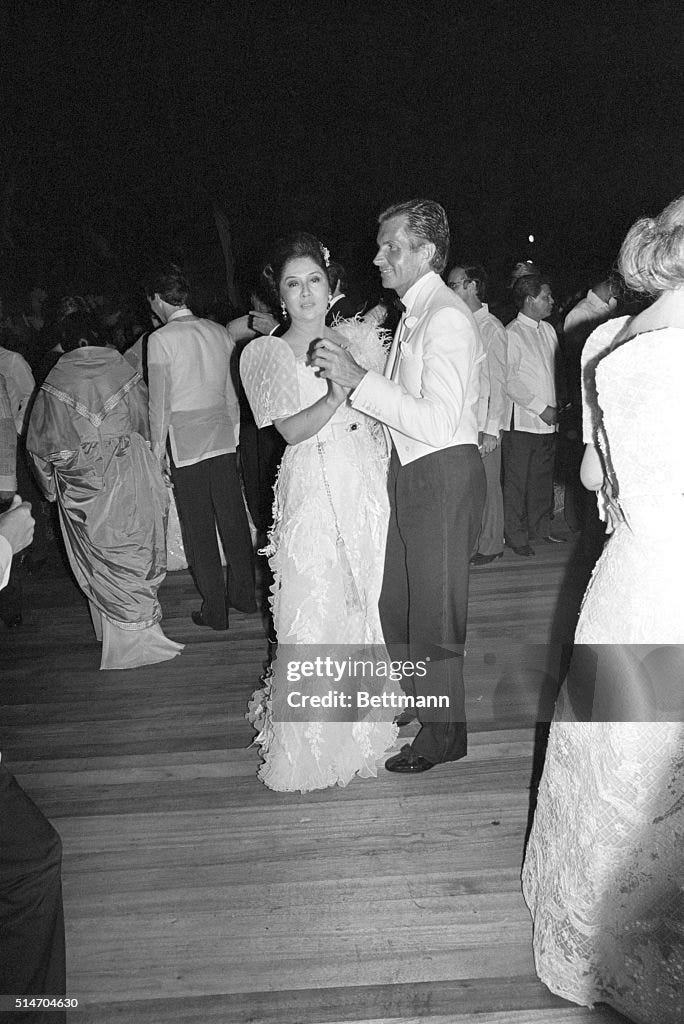

Nothing captures the era of credit in the shadow of human suffering like this photo of our First Lady, Imelda Marcos. Partying in a building constructed in record time (less than a year) just to host this festival. There were supposedly at least a hundred workers who died, but no real number can be ascertained. It is said that the building remains haunted. They remain but unfortunate ghosts of capitalism and credit.

Dear Reader,

This is one of the toughest entries I have written and I probably did not dive deep enough. There are so many economic principles and assumptions that need to be disentangled. Indeed, the producers/mercantilist view informed me how banks/bureaucrats with different mental frameworks negotiated to shift countries towards liberalisation. Thanks,

!I never thought an IMF-WB loan could be so personal and the source of so much suffering and turmoil. The sad thing is ‘deregulation,’ that is another keyword, ended a self-sustaining economy.

Onward,

Melanie

Round-Up

The keyword here is structural adjustment. It is an economic and banking term used by banks and lending agencies within the framework that the balance of payments (import-exports) and growth must be enabled in order for debtor countries to repay their loans. But what happens is that countries like the Philippines, which followed the rules of liberalisation, i.e. all debts must be paid, effectively quashed its own chances of loan repayment.

Structural adjustment decimated local industries, especially the agricultural sector and opened the market to cheap goods. The Philippines case is unique among other countries because we put into law and policy the automatic payment of debts, costing the country at least 12-15% of its annual budget to interest payments alone. It is nowhere near paying off the trillions in debt. This has kept the country in poverty despite any political changes.

Sources:

Bello, Walden. 2009. The Anti-Development State: The Political Economy of Permanent Crisis in the Philippines. Manila: Anvil

Bello, Walden, David Kinley and Elaine Elinson. 1982. Development Debacle: The World Bank in the Philippines. San Francisco, CA: Institute for Food and Development Policy

Broad, Robin. 1988. Unequal Alliance: The World Bank, the International Monetary Fund, and the Philippines. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Hudson, Michael. 2015. Killing the Host: How Financial Parasites and Debt Bondage Destroy the Global Economy. California: Counterpunch Books

Find your way around: the book outline

Re-read the previous post:

Chapter 12 (Part 3): Debt Imperialism: Bank Loans as Modern Tribute

The new tributary order demands debt peonage as part of the loan repayment

The founding members also consisted of lower-income countries such as the Philippines, Ethiopia, Nicaragua, among other smaller nations. The G7/8 nation group carry the majority of the voting rights. See Britannica entry.

It was a concept to denote political affiliation, but it also referred to income-poor countries that happened to be located in what is now called the Global South. This category also fitted the dichotomy between former colonies (South) and their former colonial masters (North). It was easy to see the continuity in the twentieth century. The raw materials from the South were exported to the North for processing, manufacturing, and eventually re-exported back to the South. The term came to increasingly refer to underdeveloped countries racked with corruption or to a cultural difference as its cause. For a historical review, refer to Tomlinson 2003.

In fact, this was almost textbook, but also how political activists used this explanation to make it simpler for their audience.

Compare this to the official description. Twenty million is equivalent to about $775 million at a 3.7% inflation rate.

Book VI, Section 26, Number 2 of the 1987 Administrative Code, by the Department of Budget and Management. This is word for word, an exact provision from the Presidential Decree 1177, Section 31 on Automatic Appropriations. Thanks to the Freedom from Debt Coalition for the reference.

EDSA is the acronym of the main highway artery of Metro Manila that links the North to the South. It stands for Epifanio de los Santos Avenue, named after Filipino writer, historian and journalist—a public intellectual.