Chapter 8: The Axial Age (453-221 BC)- Materialism 1: The Pursuit of Profit

Did the pursuit of profit in China came after the coinage-military-slavery complex of the Axial Age? Mostly no, but with an interesting caveat.

If you are new here, we are reading David Graeber’s Debt: The First 5,000 Years. Catch up and join us on Thursdays in 2024. My first slow read here on Substack was David Graeber’s The Dawn of Everything. These two books showcase his thesis on the development of humanity by looking at how debt evolved and how people organised themselves and their world. Unique among his peers, Graeber still asks the big questions in anthropology.

Dear Reader,

The time change always bothers me. Though it is only an hour, I feel my body lags. I cannot wait for when this ridiculous time change ceases. Like, now. I’m going for winter time. You can enjoy the sun during your breakfast in the summer. Can a large body such as the EU agree on this? I hope so even at sludge speed. In the meantime, we residents continue to feel its effects…

On my radar, I have collected a new stack of fun books to read. One of which looks at the second half of our adult lives, Strength to Strength. My girlfriends recommend this and so far, it resounds.

So far, chapter one hit me so much. He provides a social science study of decline and hopefully new success. One work I was thoroughly impressed with is Barabasi’s The Formula: The Universal Laws of Success. Fun!

Surprisingly, we’re still in the same chapter, Chapter 9. This is a long and complicated discussion about the Axial Age. So much has happened. We have been talking about armies and the financing that accompanied them. We have not talked about the philosophical movements that happened. This might be the time to do so.

Not cold yet but everyone is wearing thickset jackets!

Melanie

The story of profit/greed

Graeber presents a dazzling opening: the Axial Age’s coinage-military-slavery complex resulted in thinking and writing about profit.

Since we know that not all the armies were paid in valuable coinage, Graeber’s hypothesis is flawed.

Impersonal markets emerged from the fogs of war and supplying armies.

This is false.

Earlier civilisations traded on a purely transactional basis without large armies (see Mesopotamia and Indus Valley). Furthermore, the large Chinese armies were compensated without using state-minted coins.

Given that, let’s see what he wants to actually develop.

He follows his first formulation with the idea that the Axial Age was when the language of profit and greed conquered our minds. Rather than the relationship between ‘coinage and philosophy,’ as Graeber proposes, I see it as an outcome of the socio-political military reorganisation of society.

The common denominator across these geographic areas and small polities was a warrior-based society. During the Warring States Period, it became a watershed moment when the business of statecraft could now be disabused from a purely religious or ritual basis. This gave rise to several prominent thinkers whose ideas were written to enforce a top-down power structure that maintains control and war readiness.

Philosophy and the Profit Mindset

Unfortunately, Graeber uses the Chinese case to support his argument. Based on our three addenda posts (here, here and here), Graeber faltered.

We know that coinage did not coincide with the growth of Chinese armies

We know that the defeat of the Zhou in the Autumn and Spring Period led to the separation between ritual with the craft of war and governance during the Warring States Period

We see the decline of the aristocratic warrior and the rise of the plebian soldier

However, if we take his argument to the next step, he observed that the writings during this period became instrumental and rational. His observation is not fully unfounded.

Moss Roberts, in his chapter on Confucius (551-479 BC) and the other philosophers of that era (673), noted that the Analects, a compilation of ideas and sayings attributed to Confucius by his followers, only had the term renxing or xing ‘human nature’ appear twice! Roberts said that the use was not even significant. It would only be at the end of the fifth century that this concept would be debated.

Notably, the term does not appear in the Laozi and has no significant role in the Mozi.

Moss Roberts (673)

In other words, the instrumental turn was due to the concern over statecraft. Thinkers at that time thought a lot about the problem of governance, control, and how best to rule by any means possible. The formal separation of statecraft meant that specialist knowledge became highly developed. I believe this was why Graeber caught on to the idea of greed or practicality as the reigning mindset of the period. The objective was control and conquest.

Duality of good and bad

Graeber’s idea about profit/greed fits into the debate on statecraft and the nature of man for millennia.

One of the interesting developments during this period was the growth of Chinese philosophy related to governance and ethics. Part of the reason was disgruntlement but also high levels of social mobility among low-level aristocrats.

These disenfranchised aristocrats, commonly referred to as part of the shi 士 class, gave birth to these philosophers. Shi is translated by Andrew Meyer as ‘knights’ or aristocratic warriors. They were part of the hereditary aristocracy who served under the command of a local lord but had no higher title or a temple in which they could preside over ritual. Without any ritual role, they had no prestige or status. They were reduced to simply being a hired hand. The shi class suffered from the dilution of their social position due to the higher birth rates and genealogical distance from the core ancestral line. They were relegated to wandering as a swordsman, teacher, or even a farmer despite their aristocratic roots.

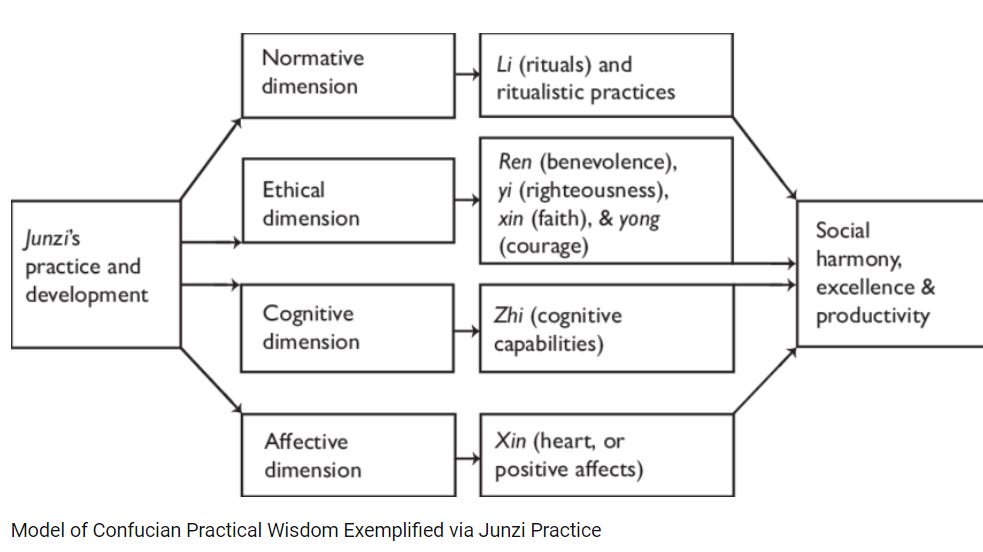

No wonder, we have a proliferation of learned people without social position. The rise of the bureaucracy meant there was an opportunity to climb up the social ranking. Confucius was one of those who held public offices and thought about social problems. Confucius writes about the ideal man, junzi, the son of a ruler. This person has character and intelligence. He is most famous for advocating filial piety and modelling the family as the ideal form of governance. Another shi class member was Mozi (Mo Di 470 - 391 BC) who expanded Confucius’ narrow view of family love to encompass the love towards other families. This is a kind of universal respect that crosses polities and families.

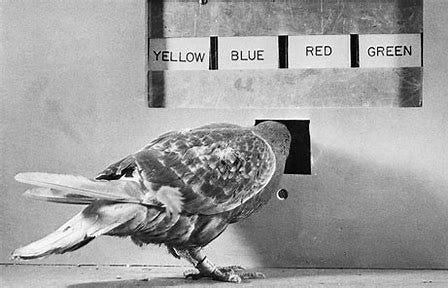

It seems the thinkers opposed those who believed that cultivating human nature is a losing proposition. The Legalists, the most prominent of whom is Han Feizi, believe that the rule of law and harsh punishment is the best form of governance. Role models are out; enforced conditioning is the best way forward. This is what Moss Roberts calls absolute behaviourism. Think of a salivating dog hearing a bell to receive rewards or electrocution. This is how people must be ruled.

To teach people to be benevolent and righteous is the same as saying you can make them wise and long- lived.

Han Feizi from Roberts (682)

In this context, Graeber’s idea of profit and its early documented birth in China is attractive. He found one entry of the concept of profit and interest.

li, a word first used to refer to the increase of grain one harvests from a field over and above what one originally planted

(not to be confused with li to refer to ritual)

David Graeber (239)

It is true though as far back as the Shang Dynasty, conquest required resource surplus.

Graeber wanted a causal relationship between the profit mindset and the military impetus in Ancient China. His initial formulation was weak because the Chinese armies did not require a coinage system as compensation for its massive numbers of professional soldiers.

However, his observation of the profit mindset is plausible given that:

There seems to be a turn towards a rational practical approach mainly due to the separation between ritual and governance.

The rational impetus to social life led to specialist materials coming out of the Warring States Period regarding military strategy, diplomacy, and law

The philosophical conversation was dominated by the best ways to tame human nature and formulate the rule of law

Indeed, a military society requires a combination of the profit drive, instrumentality, and violence to succeed. However, this precedes Graeber’s coinage-military-slavery complex thesis for the Chinese case.

Round-Up

There is a flaw in Graeber’s argument. The profit motive is not an outcome of the coinage-military-slavery complex, especially in the Chinese case. However, his second-level observation of the shift to instrumentality remains useful but weak overall.

The flaw:

The profit mindset is not an exclusive outcome of the coinage-military-slavery complex. The Chinese case has little evidence to support this.

Instead, I argue that the profit mindset accelerated with the military polity model that the Warring States Period preferred.

The plausible:

The profit mindset is a result of the instrumentality stemming from a warrior-driven military-backed monarchy

The separation between ritual-based rule and the craft of governance is a precursor to the instrumental approach to social life

The body of philosophical work during this period debated for and against instrumental-based governance.

Graeber’s thesis that the profit mindset stemmed from the coinage-military-complex does not apply to the Chinese case. His observation on the instrumental turn in the Chinese case is weak but highly plausible and useful for discussion.

Sources:

Michael Lowe and Edward Shaughnessy eds., Cambridge History of Ancient China

Elizabeth Childs-Johnson ed., Oxford Handbook of Early China

Andrew Meyer, Chapter 30 in the Oxford Handbook of Early China

Moss Roberts, Chapter 31 in the Oxford Handbook of Early China

Re-read the previous post