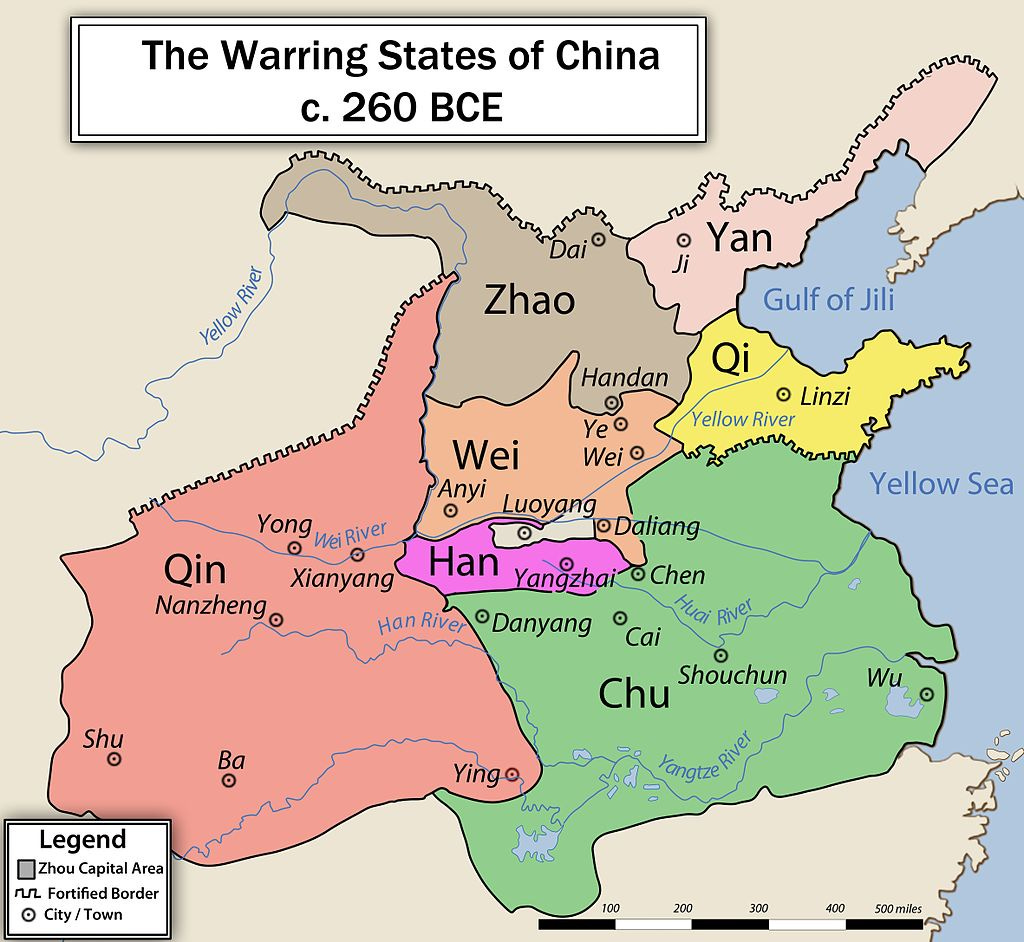

Addendum: The Rise of Bureaucracy and Professional Armies: the Warring States (453-221 BC)

From the Shang to the Zhou until the Warring States, coinage expansion did not coincide with the rise of Chinese armies. Graeber's argument is not supported here.

If you are new here, we are reading David Graeber’s Debt: The First 5,000 Years. Catch up and join us on Thursdays in 2024. My first slow read here on Substack is David Graeber’s The Dawn of Everything. These two books showcase his thesis on the development of humanity by looking at how debt evolved and how people organised themselves and their world. Unique among his peers, Graeber still asks the big questions in anthropology.

Dear Reader,

I definitely miss writing here every Thursday. It is good to be back. However, I have overlooked taking one more exam. I will have to create a work portfolio. Ugh. One more thing to cross off on my checklist. I have passed two exams so hooray! The results for the other two will trickle slowly in the next couple of weeks. It is a relief to finish (and hope not to retake any!)

I have been complaining about my lack of focus and high distractibility. However, one discovery I made recently was when I was immersed in reading, it magically reset my brain. This was at least three hours of reading. I had allowed my mind a long period of uninterrupted focus. The results may be temporary, about six hours and more, but I am ecstatic about how my distracted brain quieted down. What an experience!

It is hard to find a truly immersive book. This is only the fourth book this year that I marked five stars. (It will be five stars once I finish it!)

I hope you find your true pleasure read.

In the meantime, back to diving into ancient China once again…

Melanie

From fragmentation to recentralisation: the struggle for a state

The story of this period is about political fragmentation and reconstitution. As I read the two main sources of this series, the Cambridge History of Ancient China and the Oxford Handbook of Early China, the chronology is to problematise the one capital S state.

The Warring States Period has been characterised as a period of political reunification. But it is only if you follow the political evolution that culminates with the central state as the pinnacle of development.

Let me try something and reverse this analysis.

The Zhou was unique as it was an attempt to create a universal ritual-based culture. Mostly, it was successful on the cultural front. It failed not on the governance aspect. They could not maintain allies because of the system of devolved power to its ministers, what Yuri Pines calls the hereditary ministers. These ministers were awarded ‘hereditary allotment’ which consisted of villages and territories under their control.

The allotment’s master commanded all of its economic and human resources; the allotment’s inhabitants paid him taxes, served as auxiliaries in his military forces, and owed him their exclusive allegiance. The allotment was ruled by the master’s personal appointees, mostly his kin and retainers

Yuri Pines, p.502-503 Oxford Handbook of Early China

Instead of fostering loyalty to the Zhou ruler, the people owed their allegiance to the local lord. It is no wonder that they would later be defeated, flee and escape to the Eastern capital, designating this period as the Eastern Zhou or the Spring and Autumn Period. I would like to think of a large central entity like the Zhou as an exception to the rule. What we actually see are autonomous and semi-autonomous polities and groups waiting in the wings.

It appears that the ritual-based system, though prestigious and respected, was not enough to keep a large kingdom intact. Unlike the Mesopotamian and Indus Valley examples, the Zhou was missing elements of the central bureaucratic system that would maintain a large territory without an army. I am talking about common weights, measures, or possibly a credit record recognised elsewhere in their trading networks, for example. Or a redistribution system in their temples similar to the Mesopotamian example. It did succeed in imposing its culture throughout the millennia. Bronze artefacts continue to be found in burial practices up until the Warring States Period. Eventually, the Zhou culture formed the backbone of Chinese culture.

The quintessential problem was how to create a governance apparatus that adhered to the single-ruler model. Gone are the egalitarian system seen in the Neolithic age.

The military state model: the professionalization of the bureaucracy and army

Similar to the Kshatriya warrior states of Northern India, the multiple Chinese polities, all the seven prominent in the written record, and smaller ones had kingdoms with a military arm. No people’s assembly were known or successful, except for the capital-dwellers or guoren 国人 who exercised their influence because they were the

farmers whose land was located outside of the city walls

petty nobles

merchants

servants and retainers

artisans

These people were the armies of the ruler. During times of disaster or emergencies, a people’s assembly would be called. Rulers and ministers would also cater to their needs by cutting taxes, cancelling debts or feeding during a famine.

However, these one-off and rare occurrences, argued by Pines, were different compared to the Greek and Roman city-states. The Greek/Roman people assemblies were part of the decision-making process. This was not. Pines argues that the Chinese case is a reaction to chaos in the system. The elimination of chaos also eliminated the need to consult the people. Order was paramount.

Elimination of the hereditary governance

The prelude to order is to establish an efficient ruling apparatus. This period marked the separation of the ritual function from governance. Qin diplomat, Shang Yang 商鞅 (338 BC) was the architect of the twenty-step merit-based bureaucracy. It is open to males without regard to pedigree or economic status. However, the lower eight ranks could be achieved through purchase or military achievements and they can then go up the ranks.

The focus on skills and specialisation is what Galvany calls the ‘instrumental rational’ approach to governance that characterised this period. This is also especially true for the creation of a professional army.

The professional army

The specialisation streak resulted in military strategists and the proliferation of battle literature during this period. The Art of War is one of many. Unlike the period of the capital-dwellers, the Qin polity documents recorded the establishment of the universal military conscription across the population. No longer will serving the army be tied to kin or ritual basis, as in the aristocratic warriors in the Zhou period.

The power of any people assembly is useless in the face of population registration and surveillance. The movement of the population was also controlled through passports and checkpoints. For its army, the Qin used a five-household mutual responsibility system. Here, every household commits one male member to serve the army. A squad in the army consists of five men. The mutual responsibility system ensures that any act like desertion will be reported by any of the four families and treated as a crime. This regimented control transformed inexperienced individuals into soldiers.

It was not just the army that transformed but the logistics and economy behind it. Galvany describes it as an agro-managerial approach to state building. This means that much of the iron technology was redirected to agricultural implements to transform barren landscapes into productive farms. With the army at the centre, food and other resources were required to keep the conquest machine going. This enabled the armies then to march hundreds to thousands of kilometers extending the territories of the polities.

Soldier salary? Nothing mentioned.

Despite the professionalisation of the army and record keeping, their salary records did not survive. Or were they even given one? Since every family had surrender the time and labour of one valued member, it is unclear how the men were compensated.

Was it through the family? Coins? Still, we have no mention of salaries. But we do know that servants and ministers were compensated in

kind (stuff - possibly grain among other commodities, textiles, house, land)

precious metals (gold, not coins per se because they are made from non-precious alloys)

There has not been any significant change from what we have seen from the Zhou period.

What has not changed

The circulation remains limited to specific polities

Every polity has its own coins

The material composition is mostly composed of lead and not valuable metals

There is no indication that coinage played a significant role in compensating the army or any of the public servants. A state-sanctioned and standardised coinage use will become more important during the unification of all warring states in China.

Round-Up

We have seen three periods in Chinese pre-imperial history (Shang, Zhou and Warring States) in which warfare and army expansion preceded coin use. I am quite fascinated by the large Chinese armies compensated without the use of coins or recorded of having been compensated as such.

During this period, we know that bureaucrats, servants, possibly soldiers or their families were paid in different ways.

compensation in kind or precious metals

commercial and private transactions were possible without coin use

the appearance of a merit-based bureaucracy did not standardise the use of coins for any transactions

Though coins existed during China’s Bronze Age up to the Iron Age, it was not used as a form of salary tokens. Perhaps, it was used for ritual purposes. Astonishingly, so little was recorded regarding this matter.

Graeber’s thesis on coinage and armies does not apply to China.

Additional Reading:

Kakinuma, Yohei. 2014. The emergence and spread of coins in China from the Spring and Autumn Period to the Warring States Period.

Re-read the previous post