If you are new here, this is my ideas page where I revisit things and ideas from my other lives. My main page is dedicated to deep and slow reading of one book a year in anthropology. I am analysing David Graeber’s Debt: The First 5,000 Years for the first half of 2025. My first slow read here on Substack in 2023 was David Graeber’s The Dawn of Everything. I chose these two books for the big questions that so few anthropologists engage in nowadays. This, here, is my sandbox.

Dear Reader,

I couldn’t turn away from an emergency visit from a friend who lives on the other side of the Netherlands! Hence, I am shifting a bit today and sharing with you an interesting cultural tidbit that I discovered this week.

If you need to catch up on Chapter 10 before we proceed to Chapter 11, you can review our previous posts here:

Today is the beginning of a warm weekend in the Netherlands. A brief visit of sun and warmth is welcome.

Onward,

Melanie

When death comes to visit

In my old life, I was a death researcher—a mortuary ritual specialist. Perhaps it is because my personality leans on a sombre tone but death is the last bastion of tradition (and it is slowly fading). It is the reversal of life—this means you can see much that is unsaid in a culture. Indeed, the core values of living culture.

Moving to Western Europe, I have seen my share of death—both church and secular services. On a lot of occasions, you no longer see the body of the deceased. Either it was restricted to the family at the time of death or the corpse has already been brought to the funeral parlour to be processed. (Or in my case, the deceased specifically willed that he did not want his body to be seen, hence any family member cannot visit or care for him post-mortem). In other words, we no longer see or encounter death in its loving form.

I still remember how the funeral parlour director told us that we could not see the body anymore—to say goodbye or, at least, touch the deceased in a way that provided closure but also the last moment of care. To bathe, dress, or just touch his frail body, even ravaged by cancer, was something forbidden. I felt robbed of the finality of death—to mourn in a specific way, that only a bodily touch renders.

It was as if the family member, simply, disappeared from view.

Grief as an emotion seems to become more and more private rather than a public declaration of mourning. It feels like we must always be happy. Even with death, we do not know how to be uncomfortable with mourning or to dress as if we are mourning. There is something unhealthy and uncompleted when we no longer display our sadness, grief, and anger over a departure.

It was not this way in the past. You can see this in the evolution of the rouwkaart or a mourning card. The Dutch love their card announcements—geboortekaart, or birth announcements accompanied by specially designed postage stamps; and the rouwkaart accompanied by the appropriate rouwzegels in the darker colour. Increasingly, the post office also offers a lighter muted colour that neutralises the sombre mood of the occasion. Or as their text says, to give more attention to the card itself. This is one of the cultural Dutch symbols that an outsider such as myself is oblivious to. Once you receive it in the mail, the recipient knows what to expect before opening it.

I am lucky that my Dutch neighbour is a collector of the past such as myself. She has the historical sensibility to keep and value her old possessions to a certain extent. Our conversation turned to mourning cards last Monday.

Evolution of Mourning Cards

Over time, mourning cards have become almost like birthday cards—less formal and more cheery. Previously, the cards were quite formal with an all-black frame to indicate death in the post.

The photo shows the black frame from the ’70s (the invitation was for my neighbour’s village friend in 1975). Back then, there was an option to also indicate the funeral visit condolatiebezoek, usually at the home of the deceased, where the body was interred, the night before the burial. Prior to funeral parlours, this practice was typical for deaths in small villages. Straightforward. Little to no personal touches and only the pertinent date/time of the church or burial ceremonies, if any. Definitely, formal. No special stamp was required.

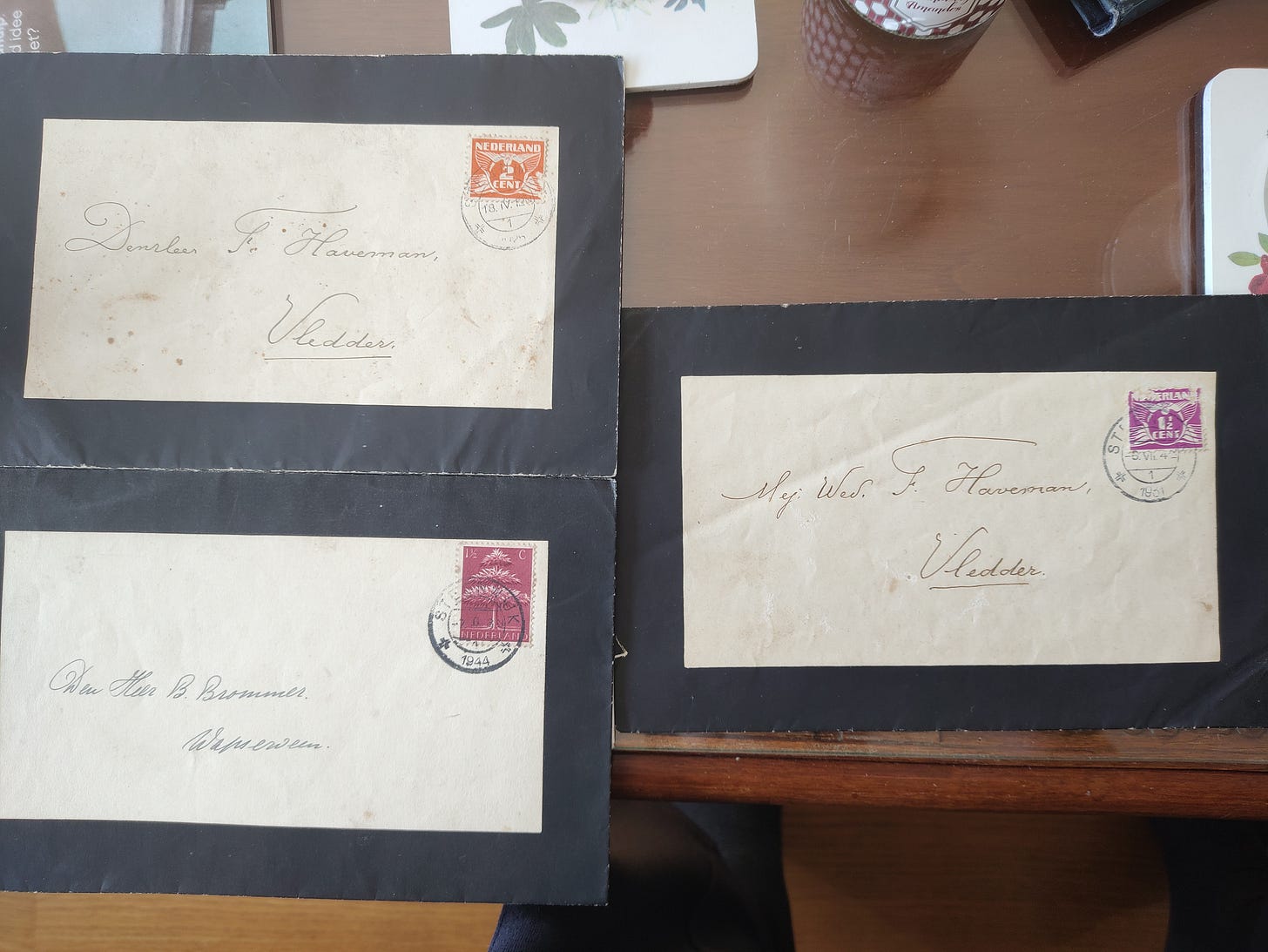

The black frame was even more severe in the 1940’s and 1950’s as pictured here. There is no mistaking what you were going to receive in the mail. The handwritten address communicates the care, delicateness, but also urgency of the situation not just to the recipient but also, to the post office and the postman.

This was to change sometime in the ‘80s (at least as dated on the earliest one we can track from her stack). The frame shifted from black to grey with a much-reduced weight. Outsiders may confuse this as some invitation to a wedding anniversary or something. To disabuse ourselves of this, we also see the introduction of rouwzegels in that characteristically marbled look of a Windows XP backdrop. The colour also shifted from grey to green and now to even a lighter shade of gold.

By the time the ‘90s (again, dating from the stack of my neighbour’s) and ’00s arrived, the frame was the lightest weight possible. It also coincided with cards that now look almost like birthday greeting cards. Gone are the heavy stock embossed cards. Hello to computer printing, no different from other greeting cards!

The cards reflect the changing views on death as another journey. There are fewer religious rites here, at least in the Netherlands. It’s all interesting.

However, what do we lose as we move away from the sombre display of loss? Of reverence in death? Of losing the visibility of the body (we mostly have urns during the ceremonies)?

What do we lose when we are always forced to be happy?

Laughing in the face of death (among other emotions)

I know what we gain from seeing and experiencing death so carnally.

Here’s one of my favourite films from 2003 that captures a snapshot of working-class Filipino life in the backdrop of death and the funeral rites of a Chinese-Filipino family. I did not know this was an official entry to the 77th Academy Awards for Foreign Film category. An unusual entry because it is a satirical dramedy and unique because it is not poverty porn, disaster tourism view of the country, crime or heavy political drama.

Turn on the subtitles by clicking the gear icon. English and Dutch are pretty accurate but without the satirical and humourous inflexions. I couldn’t help but watch it last night again and feel nostalgic.