Slow Read Book Club: Chapter 9 Postscript - The Dawn of Humanity by David Graeber and David Wengrow

Tlaxcallan democracy before Hernán Cortés

I was excitedly sharing my newfound Tlaxcallan knowledge with a fellow anthropologist who did her research in Mexico when her partner, who was learning Nahuatl, mentioned that Tlaxcala just received its first escalator in 2017. Apparently, the state was mocked and became the butt of snark.

That news boggled my mind. Quite astonishing, really. Up until today, Tlaxcala (post-conquest Hispanised spelling of Tlaxcalle/Tlaxcallan) has remained resistant to the unrestrained flow of “technology” that unwittingly brings with it capitalist values rooted in consumerism and perhaps egregious individualism. They are probably right to do things slower and think harder.

This way of being and thinking has its roots way back in their history and runs counter to the mainstream.

Tlaxcallan democratic urban design

In our last post, I briefly discussed how Tlaxcallan's decentralised form of political power is reflected in its urban design around multiple plazas or courtyards. Here we can see that Tlaxcallan has no large central or main plaza, and instead, each of the 20 neighbourhoods has one.

The houses sit atop what is called the terrace surrounding the hilltop. These terraces measure anywhere between 500 to 3,000 square meters. The space is subdivided into domestic and public spaces that may be shared with other households. This means that the wealthiest resident is restricted between 1,000 - 2,000 square meters of mansion space. Actually, the largest house that was ever excavated by Farghar is only 265 square meters! Making Tlaxcallan a rather egalitarian city compared to the mansions in Central Mexico that could measure anywhere between 8,000 to 20,000 square meters.

Their ceremonial centre Tizatlan is the opposite of these deliberate small spaces. It is outsized at 16,000 square meters with estimates even greater at 24,000 square meters before parts of it were destroyed. This means that it can accommodate, not just the 50-100 neighbourhood representatives called teteuctin, but as many as 4,000 individuals could join in religious and political assemblies and discussions.

Was this where the fate of Hernán Cortés was done? Possibly.

When Tlaxcallan discussed the fate of Hernán Cortés

Tlaxcallan is not considered a heroic city in Mexican nationalism. Most likely, it is still reeling from its reputation as a traitor state that cooperated with Hernán Cortés which led to the downfall of Teotihuacan and other Central Mexican cities. Tlaxcallan had a direct upper hand in ceding Mexico to Spain and the destruction of everything Mesoamerican.

What a lot of people do not understand is that:

Tlaxcallan was stuck right in the middle of the Aztec Triple Alliance that sought to subjugate their way of life and exact a tributary relation if not destruction. So far, Tlaxcallan have successfully thwarted all Aztec invasions

The Tlaxcallan decision to use Hernán Cortés was a democratic one, subject to debate, discussion, and eventually, consensus

Graber and Wengrow wanted to let people know that Tlaxcallan was fighting to remain independent in a sea of autocratic modes of governance. Of course, little could they foresee that the consequences would ultimately bring their destruction.

Reading colonial material

Much of what we know of how negotiations took place was from Spanish records at contact around 1519 onwards.

Bernal Diaz’s (1568) Historia verdadera de la conquista de la Nueva España

Diego Muñoz Camargo (1585) Historia de Tlaxcala

Hence, a lot of interpretation relies on ethnohistorical records alongside archaeological data for corroboration. This means that we need to read between the lines to glean how the negotiations between Tlaxcallan and Hernán Cortés occurred. One resource that Graeber and Wengrow point to is the unfinished and unpublished tome of Francisco Cervantes de Salazar, one of the early rectors of the University of Mexico, Latin scholar, nobleman, historian, and priest:

Graeber and Wengrow narrate how Salazar became enamoured of the story of Hernán Cortés in New Spain in the court of Charles V. After the death of Cortés in 1547, he sailed to Mexico possibly entranced by the plan and endowment to establish a cathedral and a university that would rival Sevilla. He would become Chair of Rhetoric and Councillor of the University with his expertise in Latin. Zena Nuttall’s critical work and eye saved this unpublished piece and reconstructed what happened to this long-lost book.

On January 24th 1558, long ignored by other historians in the Records of the Town Council of the City of Mexico (1550 to 1571), Nuttall found that the city council commissioned Salazar to write a book in which he would:

establishes His Majesty’s Right and just Title to possess this New Spain and the Indies of the Ocean and gives a general history of this new World. And because it would promote the service of our Lord God and of His Majesty and the ennoblement of this Kingdom…that it was agreed to write to His Majesty in the name of this City…to appoint the said Maestro Cervantes as His Chronicler in this New Spain…(62)

Salazar was granted two hundred gold pesos but was required to check in every three months otherwise it would be forfeited. There is some evidence that he had been writing before this assignment and this was his proof to the council. Since that time and leave of absence from the university, he would have visited Tlaxcala and Texcoco to speak to the local caciques and descendants. By this time, it would have been about 37 years since the Conquest. This made this work particularly valuable in documenting the local view such as one Don Antonio, successor to Caltzontzin of Michoacan, detailed in the last fifteen chapters:

the young Tarascan ruler “took pride in owning many books in Latin, which he understood very well and was also an accomplished scribe composing wise letters in Spanish as well as in Latin.” (67)

Between 1560 - 1566, writing delays hounded Salazar.

He was embroiled in a feud between Archbishop Montufar, head of the Dominican order in New Spain as well as the Censor of the Inquisition, and his theology teacher Dr. Chico Molina, Dean of the Cathedral of Mexico that forced him to renounce his allegiance to the latter with threat of ex-communication.

He also witnessed the persecution of the heirs of Cortes, Alonso de Avila, and other Conquistadors in Mexico and Sevilla. Despite all this, he remarkably was granted his doctorate in theology at the university and was also assigned as Councillor of the Inquisition in Mexico between 1573-1574.

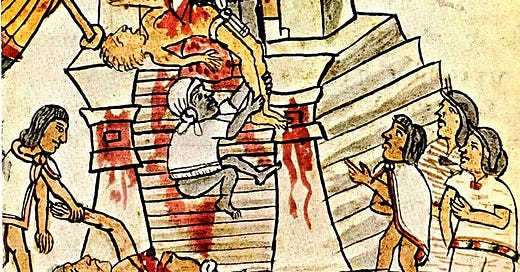

His multiple requests to go on writing leave during this tumultuous period were unheeded. His death in 1575 meant that his subsequent work went unpublished. Even after his death, the Inquisitor Moya de Contreras of the King’s Council sought to censor his contributions including suppressing Book 1 describing the religious rites and festivals. Subsequent works referring to ancient rites also by Franciscan friar Bernardino de Sahagun were censored but were luckily saved when transcribed portions of the Cronica copies and other manuscripts were sent to the librarian of the Medici Library, Magliabecci, now known as the Magliabecci MS.

While mainstream sources say this Codex is from an unknown author, Zena Nuttal argues that the Book of the Life of the Indians in Ancient Times and the Superstitions and Evil Rites that they had observed, contains the exact wording in Salazar’s Cronica. She subsequently published the Magliabecci MS (Codex Magl. XII, 11, 3) in 1903 with a critical introduction under the title, The Life of the Ancient Mexicans. Later studies such as by Elizabeth Hill Boone’s (1983) show that the Codex Group comprised six documents: Codex Tudela (including Costumbres), Codex Magliabechiano, the Crónica of Salazar, Codex Ixtlilxochitl (Codex Veytia nested within), Fiesta de los Indios, and the title-page vignettes in Antonio de Herrera’s Historia. It is through Nuttall’s efforts that recognition of the Crónica eventually surfaced but still remained without a critical introduction or translation to this day. She believes that portions of Salazar’s work can also be found in Codex Ixtlilxochitl.

The Crónica records democratic history

It deeply saddens me that I am not fluent in Spanish and therefore I cannot read Book 3 as indicated by Graeber and Wengrow as critical to see how negotiations occurred.

In Ross Hassig’s (2001) Counterfactual Histories, we see Hernán Cortés on the verge of defeat fighting the Tlaxcallans. If these people had routed the Aztecs on a regular basis then it should be easy for them to stave off the Spaniards. At the moment of defeat, it was the Tlaxcallans who decided to negotiate a possible alliance. As a counterfactual interpretation of events, Ross Hassig views the internal political competition between Maxixcatl and Xicotencatl as the reason why the battle ceased with the former supporting Cortés.

In Book Three, we find Cortés encamped outside the city walls with only their emissary Maxixcatzin, ruler of another competing Tlaxcalla province Ocotelolco, speaking to the Tlaxcallan council on the advantages of using Cortes to rise against their Aztec oppressors. He is known as someone who has ‘great prudence and affable conversation’ and we can imagine his impassioned plea that makes his position highly acceptable to the council.

A chapter is dedicated to the response made by Xicotencatl the Elder, the family leader in Tizatlan, now nearing 100 years old and almost blind, when he spells the pitfalls of an enemy within:

… does Maxixcatzin deem these people gods, who seem more like ravenous monsters thrown up by the intemperate sea to blight us, gorging themselves on gold, silver, stones, and pearls; sleeping in their own clothes; and generally acting in the manner of those who would one day make cruel masters … There are barely enough chickens, rabbits, or corn-fields in the entire land to feed their bottomless appetites, or those of their ravenous ‘deer’ [the Spanish horses]. Why would we – who live without servitude, and never acknowledged a king – spill our blood, only to make ourselves into slaves?

It must have been an eloquent speech as it caused dissent among the ranks, with opposition rising and feelings expressed within the council. (It is unclear to me whether the discussions were just from a small group of councils or a larger membership.)

What happened next according to Graeber and Wengrow is that Temilotecutl, one of the justices, came up with an agreeable solution. Cortes would be invited into the city but Xicotencatl the Younger, could ambush him along with Otomí warriors. If they succeed, they will become heroes. If they failed, they could blame it on the Otomí and ally themselves with the invaders.

In the standard account of what happened next (from Bernal Del Castillo’s recollection of the events), Ross Hassig (2001) narrates how Xicotencatl continued with his attacks but never achieved lasting victory and mounting losses. He was ordered several times to cease but he never stopped. It was only after the head council instructed the army not to follow Xicotencatl that he finally ceased hostilities. His fervor against the Spaniards would continue even as they sacked Tenochtitlan, with standard accounts, showing that he fleed the camp on the eve of the attack to return to Tlaxcallan. Cortes was said to have sent men to execute him by hanging for desertion but Hassig argues that it is because Xicotencatl remains an ongoing threat to them had he lived.

Round-Up

Based on the Crónica, the debates were said to be impassioned but also logical much like Greek debates. I do hope that one reader here who reads Spanish, will let us know the flavour of how the matter was discussed. I would assume that it approaches the rationality of Kandiaronk:

What we know for sure is that consensus and witnessing by large groups of people is an important concept in Nahua (Central Mexico) to establish legality. James Lockhart (1985) found that early Nahuatl legal documents (post-conquest) differed from comparable Spanish documents in that they contained more direct speech. Moreover, testimonies of validity involved a large number of people:

many early documents do not descend to name-listing, but say only that a large assemblage of people from the local community was present; it may be further specified that those in attendance gave their assent. Before long, however. the majority of documents came to have a list of witnesses (testigos) appended in the Spanish manner. But rather than three random adult males as in Spanish documents, in Nahuatl ones we may see all the highest authorities of the local unit, whether it be the altepetl or a subdivision. Or just as commonly there will be a list of from five to ten or more names, apparently every person present, sometimes including some youngsters, and standardly including women. In the Spanish tradition. although women could and did issue legal instruments of all kinds and gave testimony in court. one simply does not normally see them among the witnesses to the validity of documents. In Nahuatl documents, after the male witnesses have been listed, a further list of female witnesses will often follow. headed cihuutzitzirztirt (‘the women’).

These witnesses not only attested to as a legal formality but agreed to the ‘justice of the content of the proceedings.’ For example, not just the person distributing his goods, but that those were his goods or property. This is especially important when it comes to penalties for those who oppose or dispute a group consensus.

This account of Tlaxcalla reminds us that egalitarian forms of social life and political governance exist in the face of widespread autocratic regimes like the Aztec Empire. Yet, people fight to maintain their form of life and the shape that it takes is usually characterised by:

the use of violence (versus fleeing)

rank hierarchy though temporary and shifting

presence of male warrior groups

offering women as tokens of marriage alliances (but women’s participation in public discussion is a high likelihood as well)

This is the form of egalitarian societies that we see as we approach 1 AD up until the Holocene period. Would you still characterise this as egalitarian? Or something else? For Graeber and Wengrow, it remains as:

less social inequality (as seen in extreme wealth accumulation)

long-term control over others (i.e. autocratic styles of governance)

democratic forms of governance (group-led and a lot of public consultations)

Can we integrate the two and still call it egalitarian?