Chapter 6 (Part 4) Games with Sex and Death, Debt The First 5,000 Years by David Graeber

When does money become equivalent to a human life?

In our last post, we read about blood payments and how they were meant to be temporary placeholders for an unpayable debt. There are no guarantees that such social currency payments actually paid for anything. In fact, the recipients may remain violent and spiteful and extract what the payment was supposed to avoid - taking an equivalent life.

In this post, we examine an ethnographic case in which unpayable debts could actually be cancelled. This story of contrasts shows the tipping point of transformation - when money can stand in for people.

Graeber has republished this from his previous article which can be found in my Addendum Post 3. However, there is a benefit to Graeber rewriting and restating the concepts that were muddled in the early chapters of this book. I am glad that he has another chance to set the story straight.

Ethnographic Source

Much of the information from Graeber’s account was from the anthropological research of Mary Douglas among the Lele of the Belgian Congo in the 1950s. She has written a historical record of social currencies and practices transformed when the Congo achieved independence in the 1960s.

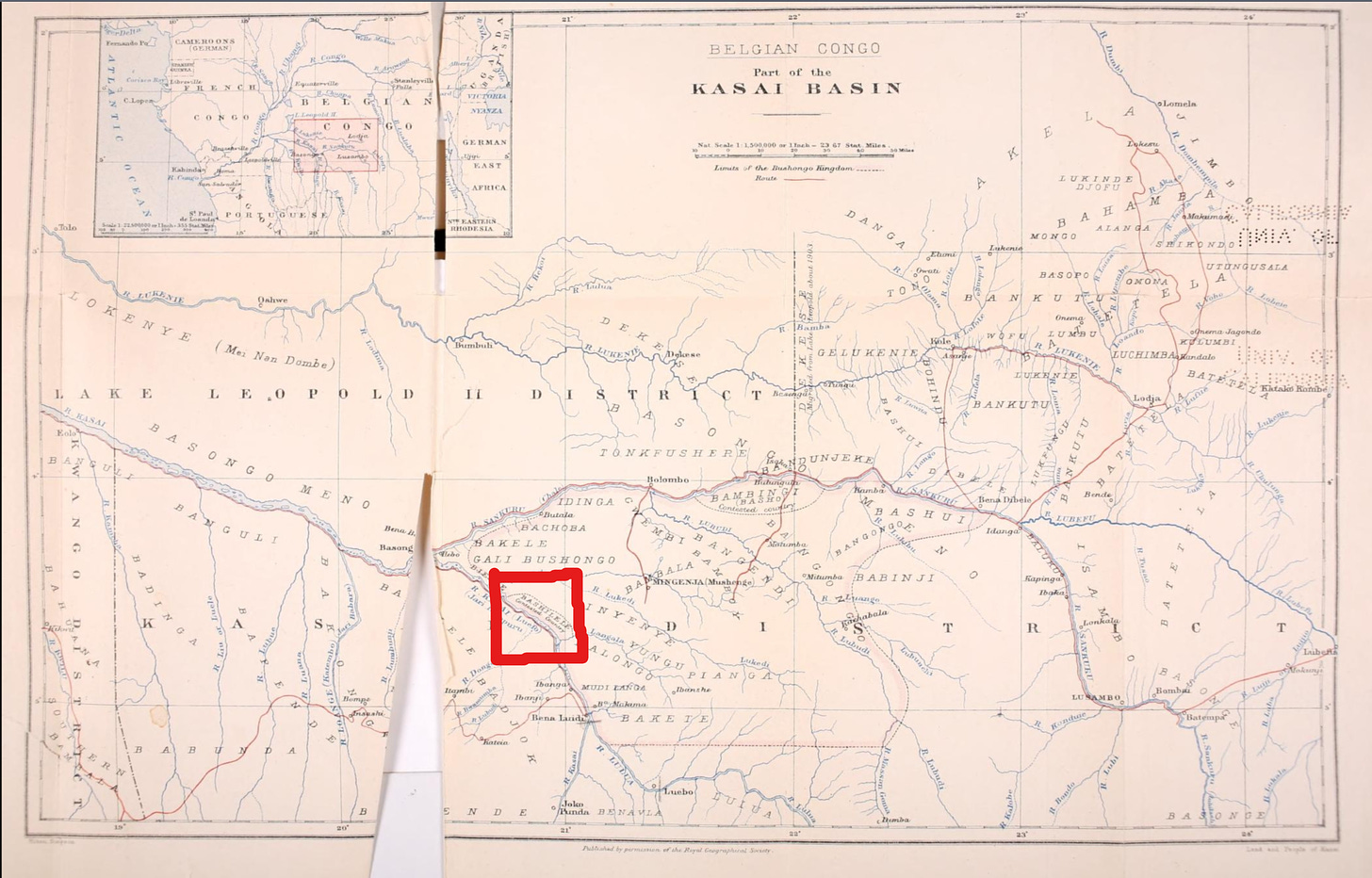

The Lele occupied the Kasai River bordering their wealthier neighbours Kuba and Bushong groups. In some of the literature, you would find labels of the Lele interchanged with them.

When money cannot buy women

Social currencies among the Lele cannot stand in for women. There is no bridewealth and the two social currencies at play among the Lele:

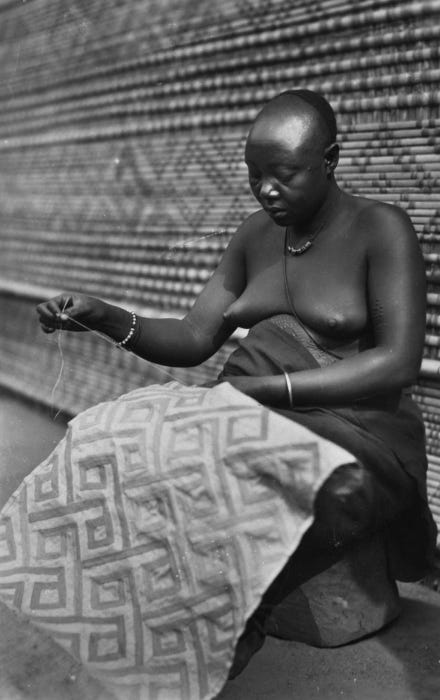

the raffia cloth

camwood - rare wood used to make cosmetics in powder form

are used for marriage negotiations in which cloths and camwood are exchanged among families.1 Between the two currencies, camwood carries more value. A hundred raffia cloths were equivalent to three or five bars of camwood.2

These social currencies cannot be used to acquire marriageable women or claim rights to any of their children. The Lele is matrilineal, which means their children belong to her mother’s clan.

However, to enter into any marriage arrangement, a man has to acquire these social currencies and only the elderly possess enough of them. It is because these gifts flow upwards. The young men weave and gift these to the elderly members of the family for everyday and social occasions. However, the elders are not expected to reciprocate. Consequently,

the social currencies do not return into circulation among the younger age set

the elder men possess more currency as leverage and tend to monopolize marriageable women

This creates a dilemma for the younger men in the community.

they lack sufficient social currency to arrange a marriage

marriageable women become scarce

Workaround: Blood Debts

A quirk of any cultural practice is a workaround to overcome restrictions. Enter the system of blood debts among the Lele. Women can be acquired in a system called the blood debts. Every death that occurs in Lele society is deemed suspicious. If you die in an accident, someone is ultimately responsible. Same with childbirth or sickness, a culprit could be found. When identified, the perpetrator now owes a victim a human life. (Whether the perpetrator is the actual cause of death is another story).

This loss of life can only be compensated with another life, preferably female.

A system of pawnship emerges to pay off a blood debt. This is when a young woman — a sister or daughter will be handed over to the victim’s family. The women become assets and pawns. The more females you acquire, the fewer chances you have of surrendering your own sister or daughter to another.

It becomes even more lucrative because pawnship is inherited. The children, including unborn males and females in the future generations, belong to the receiving family. What emerges is a game of swapping, securing, and redeeming female pawns.

…when it came to life-debts (blood debts), only men could be either creditors or debtors. Young women were thus the credits and the debits-the pieces being moved around the chessboard-while the hands that moved them were invariably male.

Summary

We see a picture among the Lele of some of the truisms of social currency that we have been discussing:

money cannot buy a person

what is being exchanged here are female lives, not money

Two different practices attempt social equivalence. In marriage, social currencies accompany the loss or addition of women from both sides. In death, a life must be exchanged. In both these cases, the pawns remain staunchly female. Even if Lele is a matrilineal group, a descent system that traces its membership along the female line, females are the pawns among men.

However, culture has a way of creating acceptable solutions, but at what cost?

When money can buy people

Before we get into the false equivalence between money and people, we need to understand the parts that make this possible. The key player here is the village itself. A Lele village has a corporate character.

it has a village treasury that owns and stores raffia cloth and camwood

it has the power to organise for war or inter-village raid

The role of the village is to help its aggrieved members overcome tensions and consequences of female pawnship.

Young unmarried men can pay a fee to the village treasury in raffia cloth for permission to build a collective house, be allocated a wife, or plan for a village raid to steal a female for a wife

Women can also opt to become a village wife, a position freed from traditional female tasks with the addition of being served by her husbands; she must be sexually available to all members, at first, but would eventually settle down to a few, then a single partner.

Both flexible practices ensure that the village treasury has enough social currency to support village wives. The latter is a resource that grows. As a corporation, the village

can acquire blood debts

own and trade female pawns

Since the Lele do not have any strict political structure, the village corporation becomes the members’ power broker. The village can mobilise age-sets to form armies. The reasons vary for raids: another village ignores their right to a pawn and or disputes in a blood debt.

A village may also take on blood debts from its members after a payment of ‘100 raffia cloths or five bars of camwood.’ This explains the strength and power of the corporate village. The village takes on the debt and will use force to extract payment and thereby, equivalence. This includes reversing what is by default the non-equivalence between people and money.

Violence is the moment when the equivalence between money and people becomes a reality.

Next week, we shall look more carefully at violence and human equivalence with the Tiv.

Round-Up

The Lele is an example of how social currencies uphold two paradoxes:

money cannot substitute for human life

money can substitute for human life

The Lele social exchanges use raffia cloth and camwood to facilitate smooth relations and help transition Lele members as husbands or wives. However, due to the uneven consequences of female pawnship and the restrictions of marrying, balancing practices emerge to diffuse tension. It includes a trade-off.

That trade-off is a corporate leadership body, the village, that accommodates payments for people. This arrangement works to support male and female agencies. The unseen cost is the paradox of quantifying money for human life and coercion that can extract equivalence through violent means.

The other uses of the cloth include paying fines, and fees, especially for paying a healer. For instance, payments of 50 to 100 cloths would be given to a woman’s husband if an adulterer was caught.

Incidentally, this same amount is the price of slaves or war captives. Although there were few captives, by 1950, the practice had been abolished for 25 years.