Chapter 6 (Part 3) Games with Sex and Death, Debt The First 5,000 Years by David Graeber

Society is the outcome of our primordial debts

A society with a social currency understands that money temporarily stands in for life. Graeber calls this the life-debt. It not only stands in for bridewealth or brideprice as in the previous post but also for when life is taken or as negotiations over a blood feud.

This takes us back to our conundrum of blood money payments in Chapter 3. Any money exchanged by the parties understands that this cannot ease or pay for grief or pain.

the real solution to the problem is simply being temporarily postponed. p. 134

When society is the debt

In a humane society with a social currency, it appears that primordial debt, a feeling of never being able to cancel a debt to society, is alive and well. Graeber here argues that it is the foundation of small groups. This is apparent when feuds and murder occur.

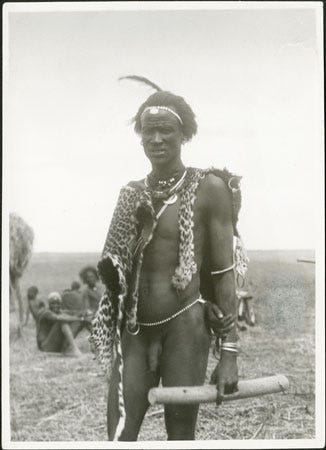

Among the Nuer, a cattle herding nomadic group in Sudan, the ‘leopard skin chiefs’ provide such mediation.

Contrary to his name, the leopard-skin figure carries no political power. He mediates between warring families and provides sanctuary for a perpetrator while negotiations occur. E. E. Evans-Pritchard documents that the priests immediately enter negotiations by identifying if any cattle are available for compensation. Usually, the victim’s family will refuse any initial offers. This is the job of the priest. He convinces them with the help of other members of the community of the consequences of refusal towards other innocent relatives and villagers.

The payment of the blood debt or life debt does not happen immediately. It usually takes years to amass resources to acquire cattle for payment. Avoidance between the two families persists in dances and ultimately the offense is never forgotten and might provoke a fight that could extract the final payment of a life. Social currency can only put the unpaid debt on hold if the parties wish to.

The Iroquois of the Six Nations made sure to avoid such outcomes. Lewis Henry Morgan documented how such murders provoke immediate reconciliation through a tribal meeting. The tribal council hopes to avert any retaliation and asks if the offender is willing to confess to his crime. If he is willing, then the council sends a belt of white wampum and the message to another council group to give to the victim’s family.

It is the responsibility of the second council group to comfort the family, reduce their agitation, and accept the wampum as an inadequate substitute for the lost life. The wampum is a confession of the crime, atonement, and petition for forgiveness, a peace offering.

It would appear that all is well upon ‘payment.’

However, this is not usually the case as it happens among the Nuer and even the Wendat-Huron nation. The wife’s relatives can commission a war party to secure a captive to kill or in another circumstance stand in for the deceased.1 Once awarded a wampum belt around his shoulders, this captive will be married to the wife, and take his name and his possessions. Effectively, he is reincarnated as the victim himself.

Similarly among the North African Bedouins, Rospabé says that the only way to settle a feud is to produce life. A daughter will be turned over to the victim’s family for marriage. If the partnership bears a son, that son will be named after the dead uncle. The son becomes his life substitute.

These different cultural cases show how temporary payments of social currency cannot cancel any debt. In fact, it seems to show how ineffective they are as payments or substitutes. With murder, no debt can ever be paid and no parity is reached among parties.

Perhaps, that is the point. Graeber argues that primordial debt is the foundation of society. The reason that we feel an obligation to society is not towards an abstract category but to other people.

Society is merely the outcome of our debts to each other.

In the next post, we ask if there is ethnographic evidence of a situation in which an unpayable debt is cancelled.

Round-Up

This post looks at what happens when social currencies are exchanged and seem to exchange for human life, such as when murder occurs among small groups. In such a society the following continues to hold:

there are unpayable debts

money is only a temporary placeholder for life

When a life is taken, a social currency of great value stands in its place as an incomplete substitute. However, this is only good if the aggrieved party accepts these temporary substitutes. Historically, in different places, there have been cultural practices in place to augment such exchanges with more equitable, though violent, outcomes.

The taking or begetting of another life in exchange for one that was lost.

It could be cold, hard retaliation but others resurrect the deceased life with the promise of a future son or an actual replacement of the deceased by incorporating a war captive into the group. A life for another life is much preferable to money.

What Graeber describes here is a society that has perpetual debts to one another. One in which payment can never be fulfilled. Therefore, he surmises that primordial debts exist within a ‘network of dyadic relations’ in perpetuity.

Society is nothing more than the debts that we cannot pay.

Graeber confesses that he assumes they were referring to male perpetrators by default. He was unsure what the amounts and situations were for female deaths from the historical documents.