Chapter 11 (Part 8): The Apocalypse in Western Casino Capitalism

Whether in France's court capitalism or England's industrial capitalism, capital extraction always portends of imminent destruction to the human way of life.

If you are new here, we are reading David Graeber’s Debt: The First 5,000 Years. Catch up and join us on Thursdays in 2025. My first slow read here on Substack in 2023 was David Graeber’s The Dawn of Everything. These two books showcase his thesis on the development of humanity by looking at how people organise themselves and their world around human values and choices. Unique among his peers, Graeber still asks the big questions in anthropology.

Dear Reader,

I’m on my third week tutoring (or more accurately studying together) with my nephew and niece on Ancient Greek. Thanks to the free access to ten modules by Maximum Classics, I’ve been enjoying learning without the pressure. I was alarmed about their lack of reading and exposure to storytelling, so together we are listening to Stephen Fry’s Mythos. It is an excellent piece of work that brings me back to my younger days studying Greek Mythology. So far, so good. Fry has such muscial lilting voice that transports you back in time! I highly recommend.

For nostalgic purposes and extra reading, I rushed to get my Bullfinch Mythology! It was a textbook that we used but now I got myself a cheap used golden-edged hardcopy that is pristine! What a find!

I’ve never been happier with a book find. To my delight, Bullfinch also compiled The Age of Chivalry (King Arthur’s Tales) and Charlemagne. It’s all here without the heft and crisp paper! Lovely to hold and page through.

Nothing delights than a discovery.

Onward,

Melanie

The Endless Apocalypse of Western Capitalism

Previously, we discussed two components of Graeber’s definition of capitalism

The figure of the gambler or the high-risk taker

The expected short decay cycle of capitalism—the rapid explosive bursts of capitalism, such as the joint-stock crashes and the ominous threat of bankruptcy

The story of Moctezuma and Cortés shows two different types of high-risk gamblers. The latter belongs to a capitalism akin to what I call casino capitalism. I borrow the term from Susan Strange, a political economist who was describing the predominantly United States situation in the 1970s:

the large debt of developing countries (and the implosion if left unpaid)

slow growth and recession during the 1970s and 1980s

instability of the banking system - volatility of credit rates

instability of the oil prices

international political uncertainty

Her formulation seems inapplicable in early modern Western Europe. However, the broad strokes indicate a common link—political instability as a result of public debt. When you think about it, this is at the core of our discussion of the early modern era of the 1700s.

It’s not what you think: The French Revolution

This detail caught me off guard. Even for a political activist, Graeber acknowledges that the crisis of the French Revolution was due to the accumulating debts, teetering on credit default, by the Monarchy. As someone who knows the bare minimum about the Revolution, debt was the last thing on my mind. Before the political rights, the story of the French Revolution was about the problem of taxation and a particular brand of capitalism.

Court capitalism

We have been discussing hypercapitalism and the extreme industrial capitalist practices as the offshoot of colonial debt relationships. Unlike its rival across the sea, France and its Old Regime, operated on a different form that carries over from the medieval period right around the Revolution of 1789.

France had a financial institutional network that historian Gail Bossenga describes as ‘absolute, patrimonial, and corporate.’ It was the polar opposite of a market-oriented, politically driven, and legally secure trajectory like Britain’s. That is, France did not have a central bank or a national parliament. Instead, the French monarchy operated as an absolute monarchical system. The financial system has been called a court capitalism, as coined by George V. Taylor in 1964. The term refers to the use of monarchical and royal nobility privileges to acquire state loans, join-stock investments, and other forms of financial speculation.

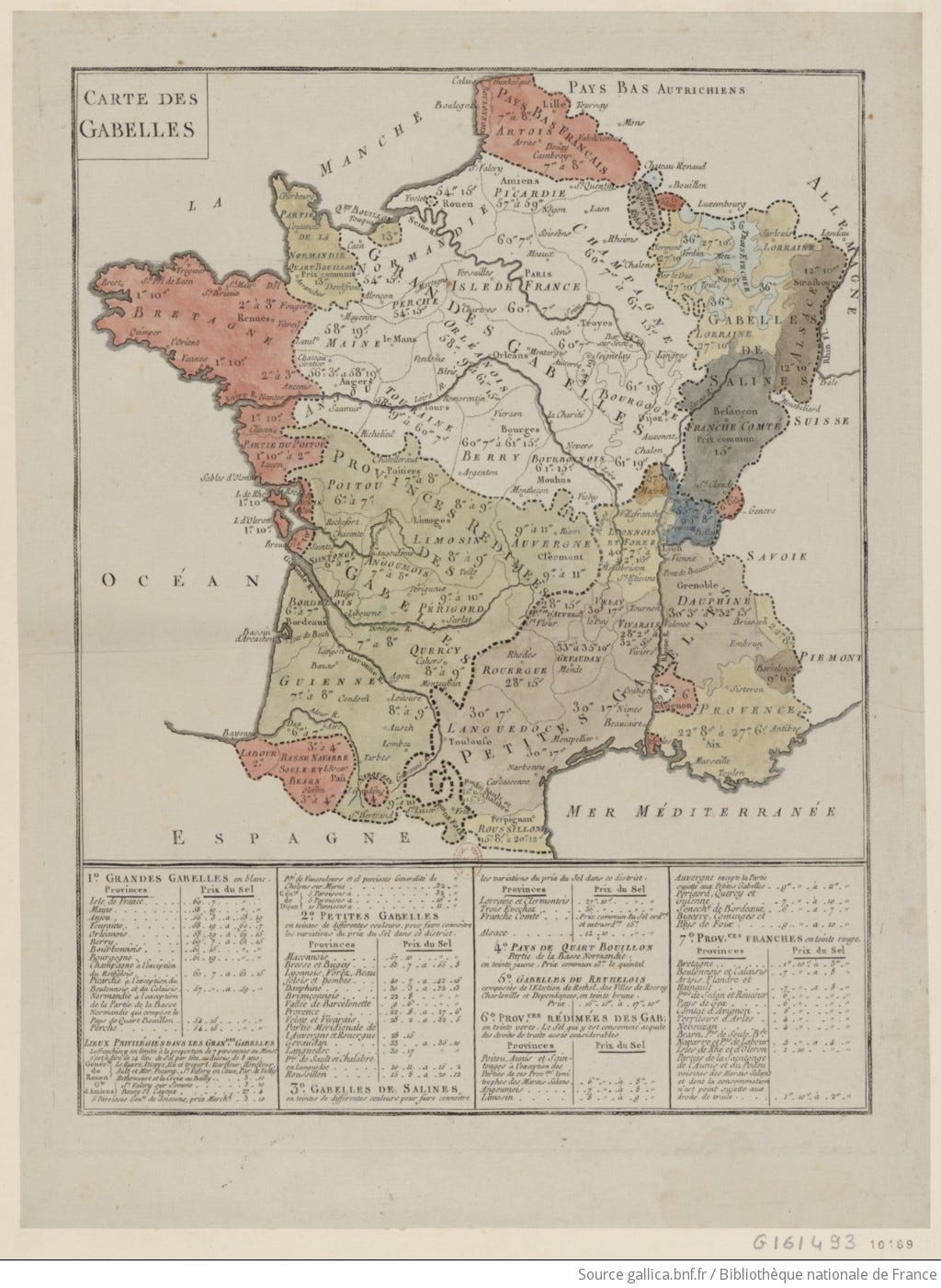

The French Monarchy did not have a permanently funded state, as Bossenga asserts. This meant that the King had to fund himself and his court using various dues, rents, and fees from the use of his royal domain. Such taxes include a land tax, taille, levied on a village; indirect fees charged from his feudal suzerain domaines, from the monopoly of salt gabelle, tobacco, excises aides, and custom duties from local in-out border crossings douanes and traites across the country.

The prospect of war meant that these sources from the peasantry was not enough. In the 1690s, Louis XIV levied taxes that included the nobility. These included a poll tax in 1695 capitation, the dixième (tenth or 10 percent tax) extracted during wartime between 1710 to 1748, and eventually reduced to the vingtième (twentieth or 5 percent tax) taken from an individual’s revenue.

This irregular system was inadequate to provide a steady stream of funding especially when the nobility fought against any long-term continuation of taxes on them. Thus, the Monarchy relied on two-long term loans called rentes and venal offices to fund itself. Rentes were annuities that guarantee revenue for the duration of the contract. Because the Monarchy was perceived as unreliable, it was left to the city of Paris to administer the rentes. These loans were sold to royal office holders and tax farmers1 who were obliged to purchase.

Venal offices were royal office privileges, titles, and functions that were sold by the Crown to borrow money from wealthy individuals. In turn, they receive tax exemptions and a monetary interest payment called gages. Both the monarch squeezed the office holders for more money when needed and office holders benefited when they used the position as a form of property and inheritance and they did not necessarily perform duties on their job description.

What we see here is an inefficient credit and funding system. It is no wonder that the bureaucracy became so bloated. In 1664, there were 45,780 venal offices of justice and finance; in 1778, this increased to 50,969 positions. One scholar, William Doyle, estimates that the number is actually 70,000 if you include army officers, members of the royal household, and commercial monopolies.

There were other short-term loans funded by tax farmers which were the most destructive to the Monarchy. The price of these advance loans included

the license to collect taxes on the government

the right to keep any profits above the license price,

full control over deduction of any interest owed from money collected

Despite these sources of funds, government bankruptcy was a regular occurrence especially during or after wars.2 In other words, France was perpetually bankrupt and had to convene a chambre de justice to wipe out its own loans or restructure them. This is in effect a moral cleansing operation. This was thought of as a morally better option than to raise even more taxes on the population. Though it provided some reprieve, it was not wholly effective as bankers negotiated for restructuring rather than cancellation.

It was in this extreme position that the Estates-General was convened in 1788 to propose a comprehensive tax reform. However, by asking for a different form of social contract with the population—a tax-based relationship in which the King owes money to the body politic—requires the King to divest his divine and absolute persona and be subject to the population as his equal tax citizens.

Hypercapitalism of England

England had effectively eliminated the onerous short-term loans and other inefficiencies when loans were backed by the British Parliament. The body has eliminated the absolute monopoly of decision-making and trust in the single person of the King. The English looked to the Dutch as a model of capital efficiency, argues historian Peter Dickson. He highlights some of the periods’ changes

Sir Josiah Child argued for a general commercial education and the equal division of estates that benefits even the youngest sons (specialised academies grew in the 18th century)

The Earl of Shaftesbury who advocated for religious tolerance to keep artisans and attract skilled labour (obtained by the 1720s)

The suggestion of codifying mercantile law and special courts to resolve commercial disputes

The reduction of the legal maximum credit rate and establishing banks like the Dutch ‘Publick Bank’ (Bank of England establishment in 1694)

The registration of land titles that enabled mortgages to be used and traded as loans and investments (introduced in 1704-9)

There are more changes in the 17th to 18th century that ensured that England as a nation had stabilised its source of public credit. Even developing fire and marine insurance among other credit instruments.

In other words, England has simply made it more efficient to extract and harness capital compared to France. It relied less on agriculture as the main source of incomes with the urban population engaged in commerce, construction or manufacturing as labourers, apprentices or servants. Despite an effective model, as Graeber observes, capitalism’s collapse in both models remain a threat. So much so that philosophers imagined the decimation of nations because of public debt.

David Hume, Scottish philosopher and economist, opined about the destruction of the nation when he wrote ‘Of Public Credit’ in 1752.

…either the nation must destroy public credit,

or public credit will destroy the nation.

David Hume from p. 321, Istvan Hont

Clearly, the unknown consequences of paper investments and credit instruments portend of societal destruction. Istvan Hont in his analysis of his work identified that Hume was primarily wary of the link between war and debt. In Hume’s calculation the only way to eliminate public debt was ‘a durable peace.’ However, since international power politics interfered with the expansion of commerce, his problem concerned: how to eliminate public debt while maintaining national security.

Hume identified some dangers with public credit:

the inability of the moderate use of public credit by the government

the difficulty of governments to manage bankruptcy because its creditor-citizens hold the offices of the state (for him, it was preferable to have the King to simply cancel debts)

succumbing to another foreign power through conquest—he is concerned when the money will be diverted to debt service payments rather than defense

Hume prefers the natural death scenario of bankruptcy that will sacrifice the property of thousands to protect the nation. But he balks at the kind of national bankcruptcy that happened in France without any economic or political benefits. In Graeber’s nightmare scenario, a personal bankcruptcy will result in imprisonment, loss of property, and for the poor—starvation, torture and death. At the early phase of capitalism, public debt and its consequences were short of catastrophe and economic collapse.

Graeber points out that the apocalypse has always loomed with capitalism because part of its raison d’être is to manufacture its own demise. A cyclical bankruptcy, the sudden wins and wealth, the threat of fall and imprisonment—all these destructive scenarios are the casino features of capitalism.

Graeber argues that once people view it as eternal, as we have now with the triumphant destruction of communism, it becomes harder to imagine life without public debt and credit.

Round-Up

The problem of public debt and the threat of (national) bankruptcy looms as the ultimate apocalyptic scenaro in capitalism. The example of the French Monarchy shows the short terrifying lifecycles of public debt/credit ending in cyclical bankruptcies of the nation’s coffers—ultimately, resulting in Revolution, that remade the contract and power between an absolute monarch with its citizens, equal now under the same tax regime.

This scenario haunts Great Britain even with its efficient tax collection system and credit instruments. The early modern period had no precedent to the extent of destruction a collapse might generate when paper money or bankruptcy ensues. Whether capitalism comes in the form of court or its hyper versions, apocalypse is its signature.

Now that we have come to view capitalism as eternal rather than a short-lived phenomenon, we attribute a different scenario of environmental destruction, nuclear winter, or planetary meltdown as part of its process. Capitalism’s eternal timescape prevents us from imagining any other life outside of it.

Sources:

Bossenga, Gail. 2011. Financial Origins of the French Revolution. in From Deficit to Deluge: The Origins of the French Revolution, Thomas E. Kaiser and Dale K. Van Kley, eds. Stanford: Stanford University Press, pp. 37-66. (excellent comprehensive source for beginners)

Dickson, Peter G.M. 1993 [1967]. The Financial Revolution in England: A Study in the Development of Public Credit 1688-1756. London: Routledge

Hont, Istvan. 1993. The Rhapsody of Public Debt: David Hume and Voluntary State Bankruptcy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 321-348.

Temin, Peter and Hans-Jochin Voth. 2013. Prometheus Shackled: Goldsmiths Banks and England’s Financial Revolution after 1700. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Find your way around: the book outline

Re-read the previous post:

Chapter 11 (Part 7): The Gambler in Western Casino Capitalism

The gambler figure in casino capitalism risks his entire life and universe to potentially win big but without playing by the rules

These were the bankers who negotiated and bought the right to collect tax. The monarchy itself used this right as a way to negotiate payment defaults and receive fresh loans. This is what is called as, tax farming. The bankers collected direct and indirect taxes and got to keep profits over the price of the lease, deduct interest owed, and even charged extra fees or premium fees for granting new loans. Though they were obligated to buy the long-term rentes or effectively grant loans to the government, they made more money off other short-term loans.

These included the years 1559, 1598, 1634, 1648, 1661, 1716, 1722, 1759, 1770-71, and 1788. It was the pattern in France. France had accumulated a debt of 1.325 billion livres for the Seven Years’ War (1756-63) and 1-1.3 billion livres funding the American War of Independence (1776-83). What was NOT in the pattern is the summoning of the Estates-General in 1788 to initiate a tax reform.