Chapter 11: Age of Extraction: The Money and Metals Grab

Is it as simple as a money grab that explains Western European expansion?

If you are new here, we are reading David Graeber’s Debt: The First 5,000 Years. Catch up and join us on Thursdays in 2025. My first slow read here on Substack in 2023 was David Graeber’s The Dawn of Everything. These two books showcase his thesis on the development of humanity by looking at how people organised themselves and their world around human values and choices. Unique among his peers, Graeber still asks the big questions in anthropology.

Dear Reader,

I just visited a Hansa town called Zutphen last weekend. Though it was pretty short, I saw how the river Ijssel contributed to the wealth of this town. You can only imagine it when you travel along the waterway. If you travel via the highways over land, it is hard to fathom how a town in the middle of the country can be prosperous in the Medieval Ages. It is one of the oldest cities in the Netherlands; settlement was established as early as AD 1100.

Goods from the Baltics, the North Sea, and Antwerp also make their way here—salt, grains, fish, wood, wine, beer, animal skins, and cloth; continuing on to the German inland.

Bonus: I discovered the best coffee so far in my rankings; it beats the Bocca coffee from Amsterdam and Barista Bar coffee (all remain in my top five) and my favourite hangout in Rotterdam—introducing, Shokunin coffee beans delivered by Van Rossum’s specialty coffee. Lightly roasted, no bitterness or sourness. Just good strong coffee. The baristas graciously shared that the coffee beans are Myanmar’s Mong Nwet. A region I did not know produced coffee until much recently to combat poppy production. I am glad that you can get this in South Holland as well. Hello, Dune!

Best tiring weekend ever,

Melanie

Origins of Capitalism(s): Asking better questions

This post is a conversation with my previous one, in which I asked: why did Western Europe develop capitalism? A question that has since been asked by people in the past, including Max Weber and Karl Marx. This comes as I finish chapter 10 of Graeber’s Debt with the European Middle Ages; it seemed logical that this simplistic query came up.

As I read more, I learned two things:

This question presupposes an evolutionary (linear) framework of society much like what Marx proposes in Das Kapital in which society moves through different stages of development culminating in the capitalist mode of production

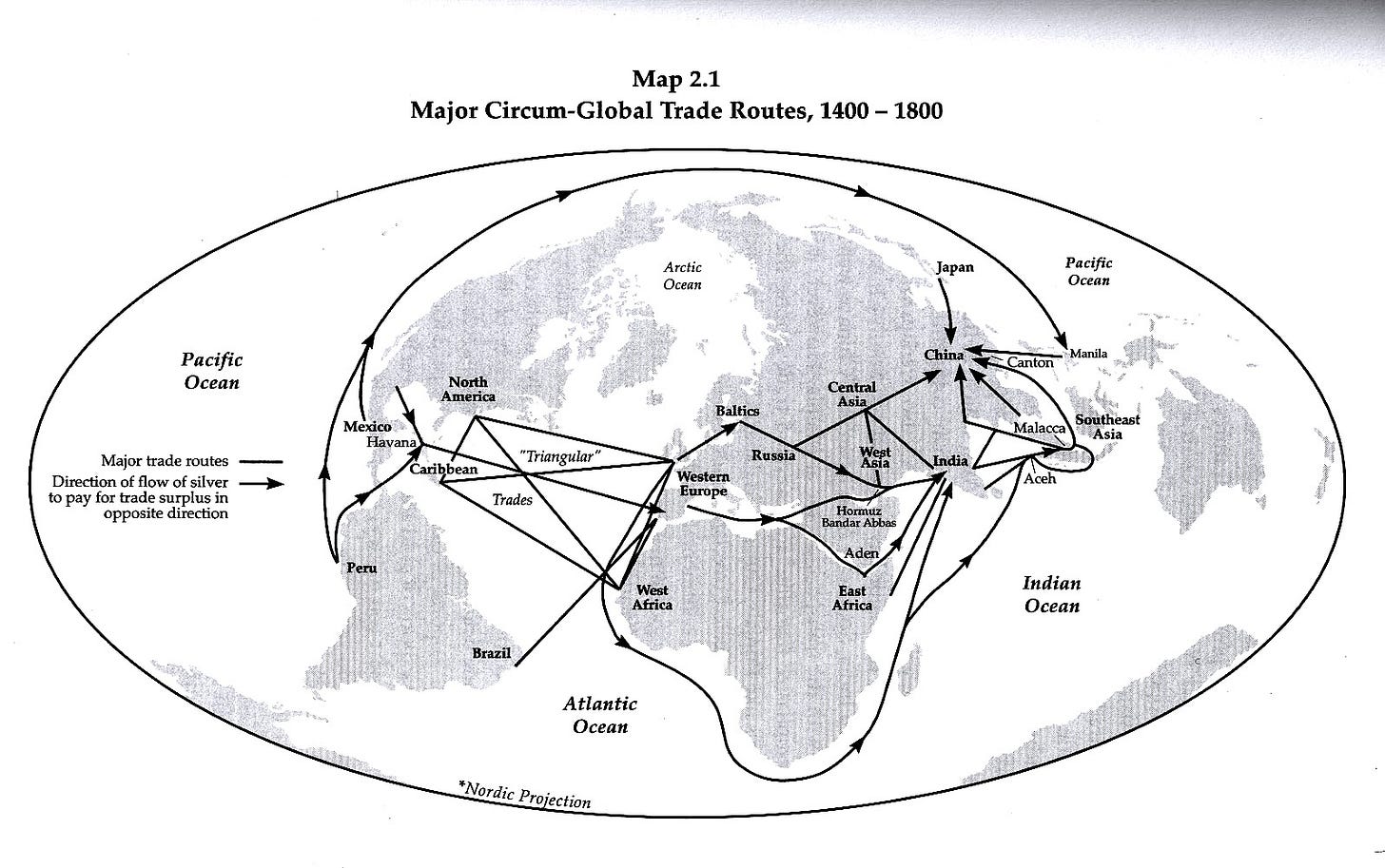

This question is Eurocentric and ignores the parallel economies in the Indian Ocean, the Mediterranean, the Pacific, and the Atlantic—all outside the confines and larger than continental Europe

Despite this, I am still left with the question, why did an industrial-based capitalism emerge only in Western Europe? Was this simply a form of hyper-capitalism—an aberration? It is beginning to look like Western Europe’s model was an exception, something taken to extremes, compared to the norm of commercial capitalism found elsewhere in the global economy.

Show me the money!

One surprising answer by Graeber and other scholars points to one practical answer—Europe simply ran out of money. Just like today, much of the luxury goods and desired commodities originated from the East—principally China, India, Southeast Asia, and the Middle East.

The Age of Exploration is simply a problem-solving attempt

to find the most direct and therefore, cheapest route to out-compete trading rivals

to find precious metals to pay for luxury and commodities

This is also the Age of Extraction.

These two reasons are part of the answer to why Western Europe had to move towards a hyper-capitalist formation because they were at the periphery of the global economic trade. This was the thesis of Andre Gunder Frank in his work, ReOrient: Global Economy in the Asian Age.

According to Gunder Frank, if we enlarge our view of the money economy for a second, we can see that Western Europe is at an economic deficit. This means that there is a lot of imports of goods and fewer exports of products. In particular, Europe was shipping a lot of gold and silver towards India and China as cash payments.

…in 1615, only 6 percent of the value of all cargo exported by the Dutch East India Company was in goods, and 94 percent was in bullion.

Das Gupta and Pearson 1987: 186 in Gunder Frank, p. 74

What was happening in Europe?

Graeber provides us with a varied picture of depression and acceleration in Western Europe.

This was due in part to the bubonic plague which struck at least five times in the mid- to late 14th century.

The massive depopulation as an effect of the Black Death reduced the working population and increased wages

The higher wages enabled wealth to accumulate for the ordinary folks. However, this party ended during the Reformation period beginning in 1517. Simultaneously, Graeber reported a massive inflation occurring during this time frame as a result of the extraction of precious metals from the Americas.

This ‘price revolution’ as it is called in the literature, was when the price of precious metals collapsed, the cost of goods increased, and the wages remained stagnant. Several factors contributed to these events:

Silver mines re-opened in Saxony and Tirol

New sea routes to the Gold Coast of West Africa that brought in more metals back to Europe

The eventual conquests by Spaniards Hernan Cortés (Mexico) and Francisco Pizarro (Peru) of the South American continent opened gold and silver mines for extraction

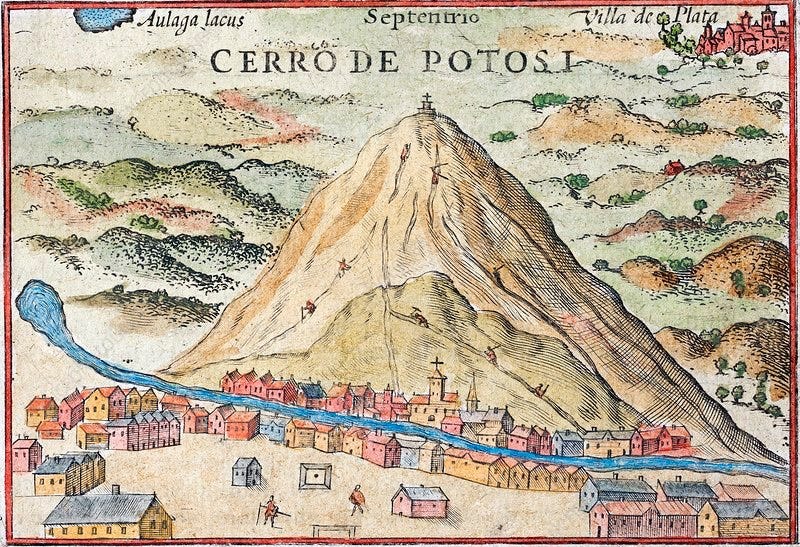

Furthermore, the discovery of the silver mines in Potosí, Bolivia in 1545 and at Zacatecas, Mexico in 1548 dramatically increased the supply.

In fact, American silver was so ubiquitous that merchants from Boston to Havana, Seville to Antwerp, Murmansk to Alexandria, Constantinople to Coromandel, Macao to Canton, Nagasaki to Manila all used the Spanish peso or piece of eight (real) as a standard medium of exchange; the same merchants even knew the relative fineness of the silver coins minted at Potosí, Lima, Mexico, and other sites in the Indies thousands of miles away.

TePaske 1983: 425 in Gunder Frank, p. 132

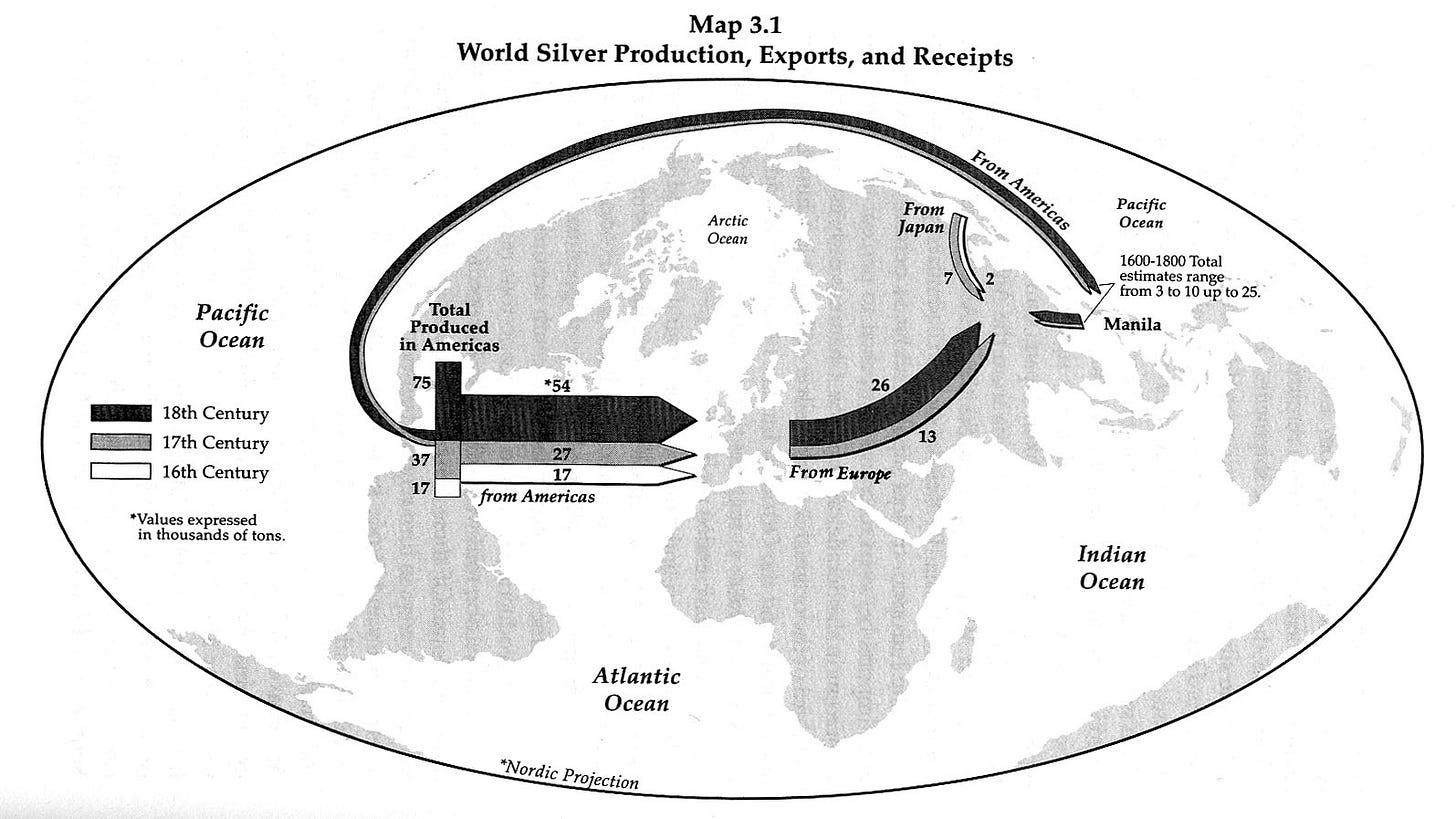

From estimates of about 3,600 tons of gold and 15,000 tons of silver in the Old World in 1500, the supply jumped to 17,000 tons in the 16th century; then, 42,000 tons in the 17th century. Over forty percent of this silver was transported eastward with 4,000 tons carried by the Dutch VOC ships and 5000 tons shipped by the British East India Company.

One scholar, Ward Barrett, estimates that about 100,000 tons of silver arrived between 1545 to 1800; about 68,000 tons remained in Europe while the rest moved to Asia. This makes this a plausible cause for inflation.

However, this was not necessarily the case in the metal ‘sinks’ of India and China. What did they do with all that silver? We’ll find out next.

Why then did hyper-capitalism emerge in the West?

Based on our initial reading, it appears that Western Europe engaged in what I called the aggressive, highly competitive, and violent tendencies of merchant capitalism—hyper-capitalism.

Its position as a voracious consumer of Eastern commodities and luxury goods perpetually created an economic deficit. This meant that looking for a cheaper passage to the East and metal resources were critical in securing balance in the foreign trade payments.

I am quite convinced, from the perspective of monetary and economic gain, that we can characterise this period as the Age of Extraction. This is one piece of the puzzle.

Round-Up

Chapter 11 opens with the Age of Exploration through the lens of money and economy. It answers one important question, why did Europeans venture into the world?

The answer—it’s a money grab. To fuel their appetites for Eastern luxuries and commodities, it was imperative to discover sea lanes that would bring them closer to China and India—the so-called, Eastern Passage. Along the way, opportunities to extract precious metals from West Africa, the Middle East (through Egypt), and South America were taken at the cost of human life and cultures. Despite the almost 100,000 tons of silver to reach Europe, it wasn’t enough.

Main Source:

Gunder Frank, Andre. 1998. ReOrient: Global Economy in the Asian Age. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Find your way around: the book outline

Re-read the previous post:

Chapter 10 (Part 9): Conclusion-Why did Western Europe develop capitalism?

The European Medieval Model is the lone survivor of a material symbolon—a fictive person (persona ficta), a de facto corporation, that ushers the capitalist age