Addendum: David Graeber's Notes on the Violence of Equivalence (Part 3)

How did we lose our social credit/money system?

If evidence has shown that the social credit system preceded physical currency, how did we manage to lose our knowledge of it? Why did accounting equivalence and debt cancellation become the dominant modes of our economic system? Graeber uses two historical ethnographies to identify the shift and how it happened. One group, the Lele (Congo) was largely unaffected by the slave trade in comparison to the Tiv (Nigeria) who deliberately avoided being included. Graeber argues the destruction of the social credit system required social violence such as one wrought by slavery in Africa.

In this post, we’ll discuss what happened to the Lele from the Republic of Congo as documented in the 1950s by Mary Douglas.

Lele’s Social Currency

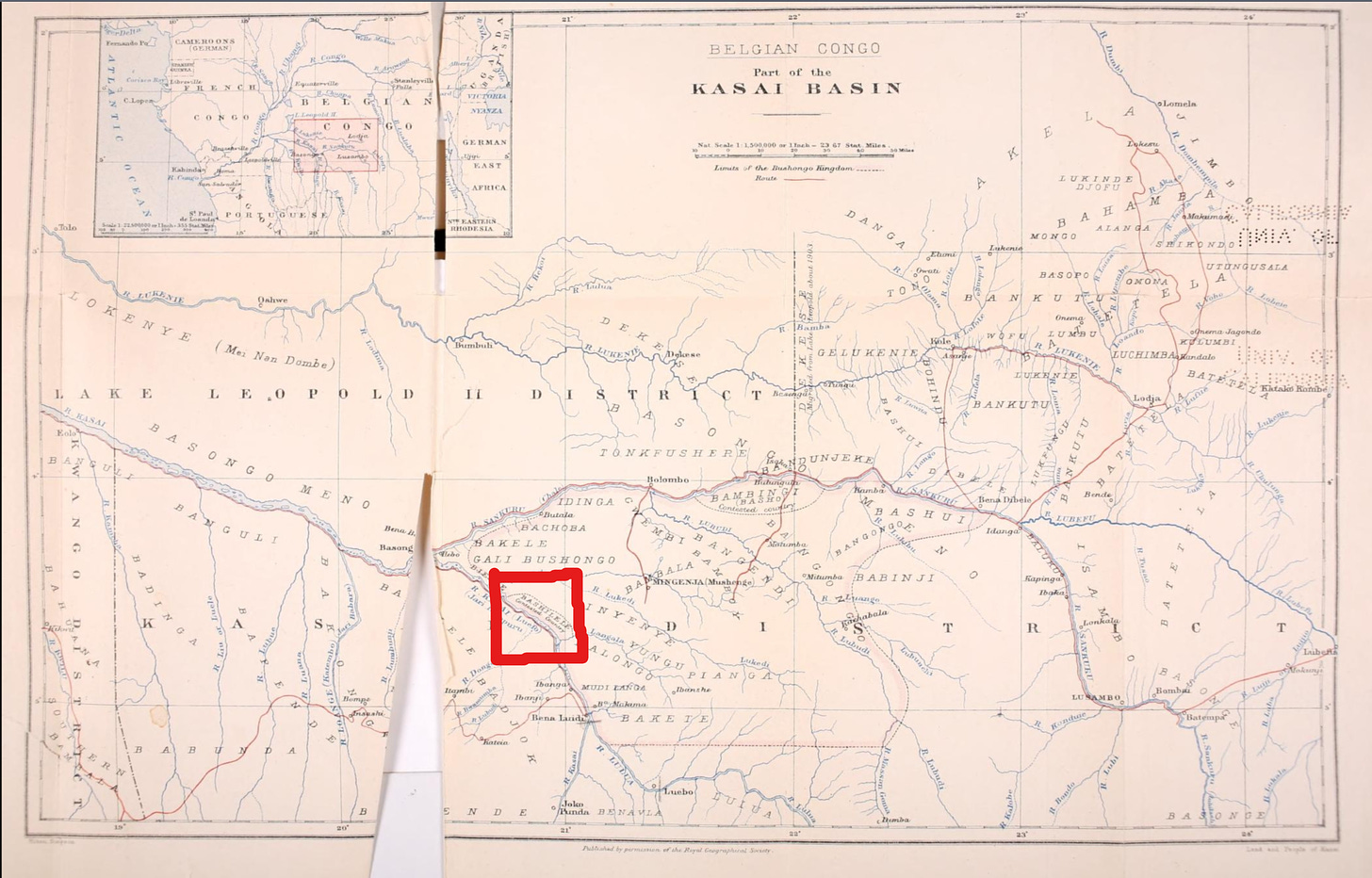

The Lele (or in some records known as Bashilele or Ushilele) of the Congo is one of several independent groups found along the Kasai River Basin. At the time of the ethnography, the population was around 10,000 people. Currently, they number about 30,000 who identify as Lele and are mostly living in Kinshasa.

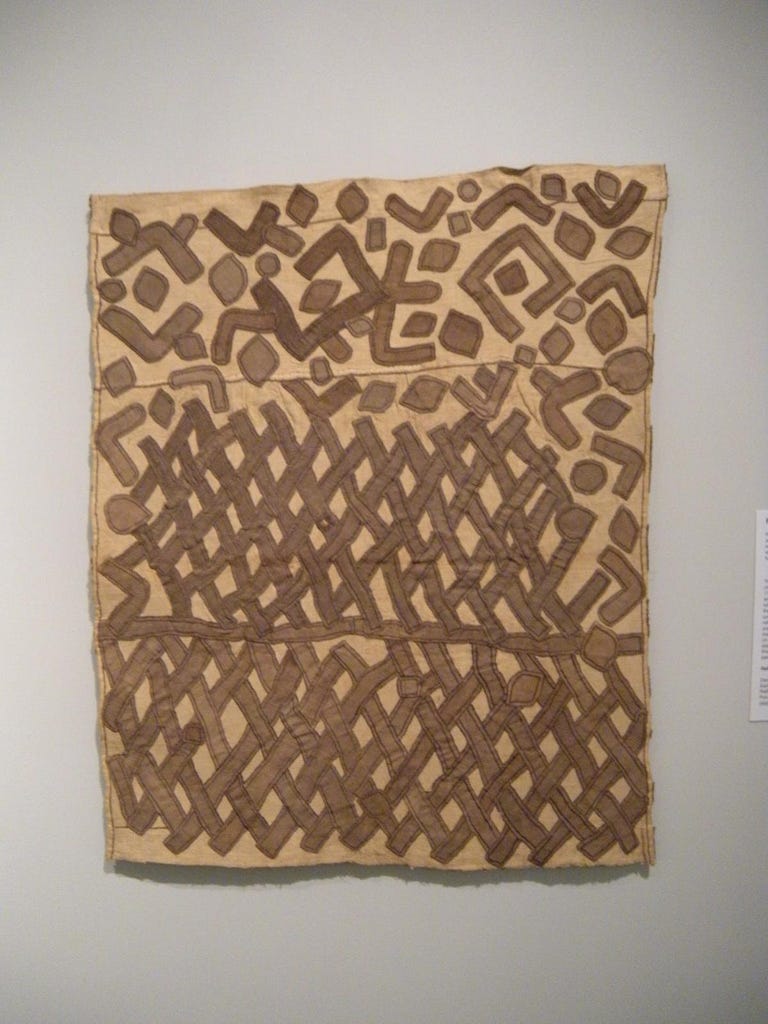

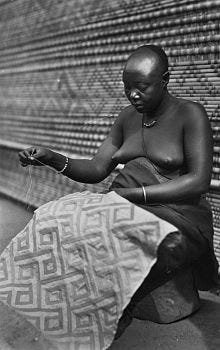

Douglas recorded then that the women grew maize and manioc and the men saw themselves as hunters but spent most of their time weaving and sewing raffia palm fibers into raffia cloth.

The raffia cloth is an example of a social currency. It was used as informal gifts to smooth relations between husband-wife, son-to-mother, and son-to-father. These are also used as formal gifts for marriage and for the transition to adulthood. The cloth was also used to pay fines, fees, and rewards for curers.

The flow of the cloth is from the youth upward towards their elders. The cloth exchange was hierarchical with the elders never having to reciprocate. It was the young men who had to turn to the elders and their friends and kin for a steady supply of cloth for exchange, marriage, childbirth payments to doctors, and fines.

Despite the value of the raffia cloth, Douglas discovered that she could not use it to purchase food, tools, tableware, or any other material good. This was quintessentially a social currency.

Lele’s ‘Life Debts’ and ‘Blood Debts’

One of the most complex exchanges in Lele society occurs in what Douglas calls blood debts and Graeber calls life debts. These debts incur for all deaths in the village. Think of it as a life in exchange for any death. If a person saves another person from drowning but dies in the process, the rescued must turn over his sister or female ward as a pawn to the family of the rescuer who died. Similarly, if a divination has identified a person as a cause of the death, the culprit also turns over a young woman (sister or daughter) to the aggrieved family.

More curiously, the Lele practice matrilineality - or rights, power, and access to resources are traced through the female line. In this arrangement, it is the mother’s brother who is important and lineage is traced through the mother’s line. Despite this, women are characterised as ‘pawns’ or the currency of exchange given to the victim’s closest male victim for every death in the village. A woman’s children inherit the status of pawnship which means that every male is a pawn but is not eligible themselves for any exchange. Thereby all the males in the village sought to acquire as many pawns as possible.1 This system, of course, is never achievable or sustainable.

women would endlessly get swapped all over again

there is no material good even with a high value that could equal a human life: not raffia cloth, camwood bars, goats, or anything could be used to exchange for pawns

consequently, women were unavailable to younger men because the older men tended to monopolise the female pawns

The result is a female shortage.2 Older men addressed this by:

allowing the younger men to pay fees in raffia cloth to the village treasury

permitting them to build a collective house ready for a wife allocated to them

organising a raiding party to kidnap a female from a rival village

One outcome is that the village attains a corporate identity with a sufficient collection of wealth that may be useful for any external negotiations. Females coming in as wives from outside the village, called village wives, may also attain a corporate identity of sorts, with communal rights by village elders to access and privileges such as sex and children in exchange for a life free from typical village obligations.

This might sound weird or even shocking practices (hence, suspending judgement or cultural relativism is critical) but generally village peace is highly valued with internal strife avoided.

Inter-village violence: the emergence of equivalence

If internal violence is avoided, external violence is acceptable and can be exercised towards another village.

Villages were protected and military units could be quickly organised for raiding or defending. The issue was always over women. If one village ignores claims over a pawn, it is a motivation to organise a raiding and kidnapping party. Deaths arising from such an action could cascade into further claims forcing a truce. This cycle of violence can become neverending.

It is only with the threat and consequences of cyclical violence that equivalence occurs. In this context, a human female pawn can be exchanged for wealth or raffia (or a much higher value good called camwood) currency. Only a village could sufficiently transact as they hold contributions of raffia or camwood currency in their accounts.

The man who meant to sell his case to a village asked them for 100 raffia cloths or five bars of camwood. The village raised the amount, either from its treasury, or by a loan from one of its members, and thereby adopted as its own his claim to a pawn. (1963: 171)

Physical violence forcibly reveal the cost of human lives in material goods.

Round-Up

What we’ve seen are two contexts of currency use and exchange in everyday life of the Lele

Irredeemable debt - when a social currency is used for life transformative instances (marriage, healing, fines, gifts, etc.) but not for commodity exchanges

It is understood that female exchanges are not redeemable through a monetary currency or even a social currency. There is no price or bridewealth practice. This means that the Lele acquire females only through instances of death or as aggrieved parties of deaths in the community.

Redeemable debt - when context determines that a human life can have an equivalent in monetary or social currency

Based on Douglas’ ethnography it is clear that threats of inter-village violence and internal violence ruptures human non-equivalence. To avoid further violence and deaths, and thus acquiring more females and their rights, a material exchange follows to cut off the pattern. Material exchange for human life is a zero sum game that erases the scoreboard and terminates a relationship.

This record of the Lele shows how a social currency operates where currency cannot buy a human life. At the same time, the Lele can calculate the worth of a human life when instances of violence can be disadvantageous to all parties.

Does our current every day life filled with micro violences (and large population size) skew our need to cut off relationships? It appears that the next step is to identify such instances to answer how we lost our ability to provide a social credit system and long-term relationship with our community.

To end this post, I would like to express how Douglas, a female ethnographer herself, observed that this Lele practice do put the control of male over female lives which does not fit our current values. As an anthropologist, it continues to amaze me the wide breadth of human practices required to solve social problems. This historical record is important to understand what we have lost and how we lost nuances of monetary systems.

Women themselves cannot hold pawns except be pawns. Only the men could be creditors and debtors.

I have skipped the more complex categories of village wives, or those who enter the village as refugees, who assume an identity of a corporate property with group rights to sex and her children. Men could coerce village wives to abide by their wants but never applied to fellow men. Internal violence is largely a potential threat and agreeable behaviour is valued highly.