Slow Read Book Club: Chapter 8 (Part 5) of The Dawn of Everything by David Graeber and David Wengrow

From village to state and back — were there Neolithic states in China?

Dear Reader,

I have breathing space this week.

You may have noticed that some of my previous posts were quite short. I had other commitments outside of writing. It was tough. And to be honest, I was tempted to just skip it. I mean, there’s no real repercussions at the moment. Except, I would know. I’d like to share with you that keeping that commitment to writing and to you, dear reader, really makes a difference. I can happily report that we are about four chapters to conclude the book soon but these sub-sections deserve more reading. I believe the results are pretty good since we now have a comparative view across different regions.

What I did notice is that the more recent the archaeological records are (3,000 BC onwards), the less we know about the sites. Mainly, the research challenges include a combination of political, looting, and modern development pressures. I am quite sad about it but hopeful and salute all the small teams and researchers who continue to forge ahead and do what they can to solve humanity’s great puzzles about ourselves.

It feels like the end but we still have Meso America to go before we re-think about urbanism and egalitarianism and whether Graeber and Wengrow succeeded in their thesis.

Thanks for reading with me,

Melanie

Yellow River Settlements

Like all previous riverine ecosystems, the Yellow River (Huang Ho) is the fulcrum point in urban development in China.

It runs for 5,464 kilometers from the Mountains of Bayan Kara in Qinghai Province and snakes its way towards the Bohai Gulf in Shandong Province. The river encompasses about 750,000 square kilometers and is home to several sizes of settlements ranging from villages to large cities.

Reading the Chinese archaeological data

Unlike Mesopotamia and the Indus Valley Neolithic settlements there are hundreds and thousands of excavated settlements along the Yellow River and other surrounding areas. In short, overwhelmingly detailed and dense. My approach was to read more broadly but whittle down specific sites and features following Graeber and Wengrow but also the Yellow River - Central Plain and the Loess Plateau in the North (Inner Mongolia). This gives us a similar Anatolia-Mesopotamia regional area to compare to.

The State Development Model

As we approach the 3000 BC mark, the advent of writing and bureaucracy means that much of the analysis is moving toward the concept of the ‘state.’ The framework that I have come across is increasingly evolutionary in approach from village to city to state. When you read the research in China, you would notice that multiple terms are used such as ‘first complex city,’ ‘ancestral cult worship,’ ‘social hierarchy,’ ‘ritual practice,’ ‘palace,’ ‘royal,’ and there are more. Much of this informed analysis comes from historical records such as Li Ji (Book of Ritual) from the Zhou Period (770-221 BC), Zhou Yi (Changes of Zhou from the same period), Zhou Yi (Western Han Dynasty 168 BCE), among hundreds of others. This made Lee 2002 remark that the main problem in Chinese archaeology is its relationship with Chinese historiography. The latter has the tendency to form the objectives of the former. As an outsider, I am skeptical of these assertions until I know more about the data and so should you be.

The project of the state is something all nations want to enforce. What Graeber and Wengrow and other archaeologists are trying to do is move away from this linear development model - from city to state or even monarchy explanation. This is where my naivety comes in handy. My approach is to temper the archaeologist's interpretation with the demonstrated evidence. If I cannot find specifics, I suspend any interpretation. I use a simplified comparative approach by looking at similar sites from same the time period in Mesopotamia, Anatolia, and Indus Valley. This sobers up our interpretation.

Markers of Egalitarianism

What are we watching out for? Graeber and Wengrow are searching for indicators of egalitarianism. So far, we have also been examining and validating some of the evidence across different settlements in the Late Neolithic period:

inclusion of public buildings - for worship or other common activities

public buildings with access or restricted access

bureaucratic governance without a centralised office

key symbolic indicators especially religion and temple structures and all the temple activities that structure people’s lives in lieu of centralised control

the change in mortuary rituals and the accompanying grave goods

female oriented symbolism versus male oriented symbolism

Much of the argument for egalitarianism is also marked by absence:

lack of monarchial related monuments or references to a ruler

lack of a centralised office

More and more, we are also looking at transitory elements or hybrid forms of egalitarianism that included:

appearance of social rank difference whether it was in residence location or burial goods and potentially wealth access

public service or labour contributed to public goods such as temple activties

bureaucratic functions that might use specialised teams of people with selected access to resources and rights

As we move to the Late Neolithic period, they hybrid forms of egalitarianism becomes even more difficult to parse as rank hierarchy increases among the population. This does not necessarily mean that a complete authority over another occurred in terms of political governance. As we have seen in previous cases, authority is limited and circumscribed in different arenas of social life. I believe that the Neolithic settlements here would be similar and different in a lot of ways.

Middle Neolithic Period (5,000 - 3,000 BC)

I thought of diving deep into this period just to see what happened prior to the Late Neolithic period that Graeber and Wengrow chose. If they focused on the Middle Period, they would have found much interesting data that supported their ideas of egalitarianism.

Several settlements such as the burial site Niuheliang (1) (Hongshan Culture), in modern Liaoning Province, which possibly traded for jade from the mines 300 kilometers away.

There is evidence that female figurines remain predominant in this time period. This site is exclusively a burial site with no nearby settlements or active cult or cult activities done on the day to day unlike the Mesopotamian and Indus Valley examples.

In contrast, there are other settlements like Dawenkou (2), near Shandong Province, where male preference over females are emerging in tomb burials. The lack of female symbolism is apparent.

What is clear is that other places had female-based artwork, but more and more evidence of rank hierarchy start to show up - the elaborate jade grave goods, male preference, and segregated burial sites. There are still common features characterising egalitarian settlements from this time period such as:

lack of individual note among these graves

lack of centralised political office or mechanisms of rule except for shared religious beliefs

existing multiple sources of food such as hunting, gathering nuts, millet and rice cultivation

These fit in with what we have seen in Middle to Late Neolithic settlements in other locations outside of China. The rank hierarchy will become even more marked in the Late period as well as a more specialised religious practice restricted to specialists.

Late Neolithic Period - Longshan 2600 BC

We are interested in the lead-up to the first monarchial period of the Shang Dynasty (1200 BC). The settlements are characterised by rammed earth (hangtu 夯土) fortifications regardless of size. These feature include the smallest village that covered 30 hectares up to 300 hectares.

Graeber and Wengrow focused on two exceptional fringe settlements from the Late Neolithic. One, Taosi, an urban area that covered 300 hectares at its peak in the Yellow River, and Shimao, a Northern settlement similar to Karahan Tepe.

Shimao (2300 - 1800 BC)

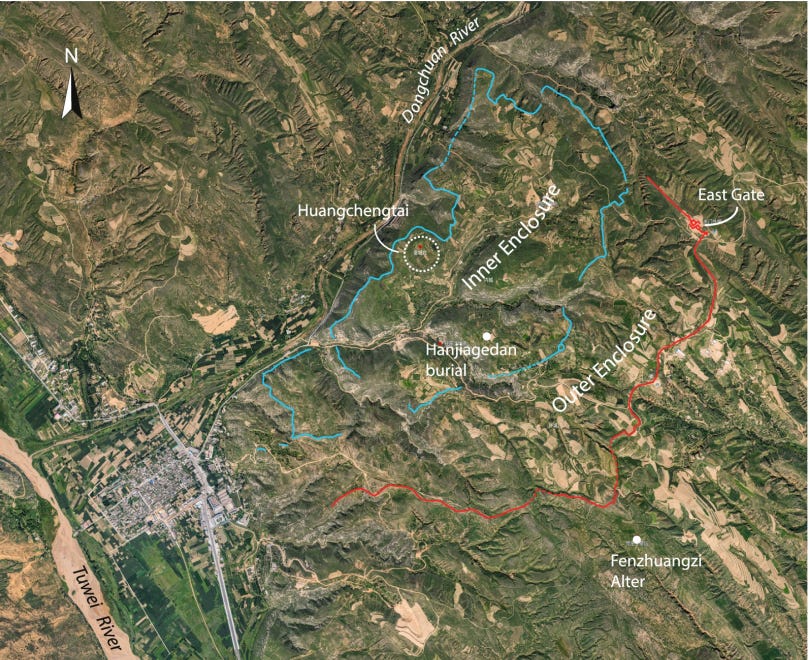

It is located along the Tuwei River in the North Central region of China, Shaanxi. It is considered in an area where it approaches the desert. Like the others, it is a fortified settlement but unlike the other settlements, it is designed against attack. It sits atop the hilltops with two enclosures, an inner and outer wall with gate towers, corner towers, and turnstile gates. At the centre is a pyramid tiered structure of rammed earth called Huangchengtai.

The inner enclosure follows the natural topography and covers an area of 220 heactares and the remaining wall runs 5700 meters in length. The outer enclosure is its extension with an area measuring greater than 190 hectares covering the length of 4200 meters. An experiment has shown that it would take 504 days to complete this with 200 people working at 1.2 meters per person.

The centre is an impressive tiered pyramid with the flat top covering over 8 hectares with a rammed earth foundation (1500 square meters) and square shaped pond (300 square meters). This is a ritual complex with finds that include stone human heads and alligator skins used for ritual drums. There is another altar found 300 meters outside of the outer enclosure, the Fengzhuangzi Altar.

The population and their dead lived within the confines of the inner enclosure. The focus of excavation largely focused on the walls and pyramid. Thus, a more robust ritual and symbolic representation of Shimao can be made. It is possibly a warrior- based society, not unlike the agro-pastoralist modality in this area, with aggression a necessary part of its every day life. It is unsurprising that they found six pits of human skulls near the East Gate as part of its foundation construction. They number from 1- 16 skulls to as much as 24 skulls primarily from young females with cut marks and burns.

The abandonment of the settlement is largely due to environmental deterioration.

Taosi (2300 - 1900 BC)

In contrast, Taosi is what Chinese archaeologists call as the precursor capital city of the Xia Dynasty. Like Shimao, it has characteristics of what scholars would attribute to a Chinese capital having fortifications, roads, storage areas, a distinction between commoner and elites, craft specialists and workshops. This meant that there was careful dating made on this site:

Early Period 2300 - 2100 BC

Middle Period 2100 - 2000 BC

Late Period 2000 - 1900 BC

Taosi sits near the Fen River in Shanxi Province and spans from a village of 60 hectares in the Early Period expanding up to 300 hectares. What is interesting in this site is what archaeologists have dubbed the Palace and the Royal Tomb.

The “palace” (could it be also a temple?) initially had a dry moat but eventually it was filled up with rammed earth wall creating a rectangular shape platform. The platform itself covers an area of 8,000 meters while the building sits at the centre measuring 280 square meters with about 18 postholes. Does this indicate an open space? Unlike what we have seen in the Mesopotamian and Indus Valley, the storage system is further away. However it does have an ice storage underneath it where chunks of ice could be dragged from the river. It is theorised that it is used to preserve bodies.

If this is a temple, then there is no distribution mechanism as part of its religious function. However, carbonized rice was found in the building so possibly food sacrifices occurred within it. We have seen the similarity with other Indus Valley and Mesopotamian cities where elite and commoner residences were found adjacent to the public building. Could the people perform secular or religious public services in this building?

The Royal cemetery is named as such because of six large tombs with grave goods attributed to monarchs such as dragon painted ceramic, ceramic drum, drums covered with alligator skin, jade axes and much more. They distinguish this from elite tombs that has 20 - 40 artefacts similar to the monarch without the tray, wooden drum or chime stone. There are roughly 10,000 total burials here with only 1379 excavated. Among that number, 556 were smaller graves with few ornaments. This tells us that there were rank hierarchy but should we attribute a monarch? Could this be also a head shaman, for instance?

This site is also remarkable because of an observatory attributed to a celestial cult around sun, fire, and heat. More practically, this observatory was used to track ceremonial, local cultivation, and local weather for 4100 years. A Taosi solar year is divided into 20 terms with 2 solstices and 2 equinoxes. Is this an indication of a different form of bureaucracy defined by calendric cycles enmeshed with religious symbolism? Quite possibly.

This settlement show indicates rank hierarchy in burial but also craft specialisation and skills with ceramic and celestial calculations. But without a clearer picture of ordinary settlements, it is hard to ascertain whether this is an example of a monarchic city or a temple city. I have not read much evidence for me to be sure.

Collapse of Taosi

The reason this city was interesting for Graeber and Wengrow was that towards the end of the Middle Period, there was an invasion or conquest that occurred in the city. Much of the spatial divisions between the elite and commoner were destroyed through burning, covering the palace/temple with earth, workshops occupied the elite residential settlement, and the mixing of commoner burials in the elite cemetery. Corpses were violated and with some evidence of torture.

In other words there was a revolution and the differences were reversed. Graeber and Wengrow postulated that a marauding group, cultural opposites of this emerging hierarchical group, burned down the city and everything that characterised it. While there was an attempt to rebuild the old palace/temple, the city overall was in decline.

Were these marauders similar to the Shimao group? In a lot of ways both are similar but quite different in their temperament and cultural symbolism.

Round Up

Egalitarianism seems weaker in the Chinese case. However, as we can see the evidence that would support egalitarianism is few despite the number of sites. This is partly due to the attention given to large areas, fortifications, and burial sites and less to the ordinary every day life of its population. This means that we hardly know what is going on in every day life.

However, some issues niggle in my head:

Does rank hierarchy automatically mean governance by elites? I am not convinced. Without using the state development model, the possibility of an egalitarian set-up is likely. If bureaucracy occurs without monarchy in Mesopotamia or Indus Valley, a ritual or religious based city can operate just as well without centralised form of government. This is what we must be critical when reading the available archaeological evidence (separate from historical documents that are recorded thousands of years later).

The centralised religious structures in these settlements convince me that there is a stronger pull from religious symbolism than elite control to rule a city. Of course, there might be specialists involved but there were clearly no specific signs of a sole monarch or a series of them. We need to know more but for sure, unlike later dynasties, there is not enough courtly evidence yet to indicate a sole autocratic ruler(s) for the duration of the long period.

What we are seeing are factors that encourage the rise of monarchical rule. External threats from warrior-based societies provided the balance against this.

Late Neolithic settlements

As Chinese scholars have interpreted, these social hierarchy would increasingly deepen in Late Neolithic settlements. A state development model is one interpretation that is quite strong since the Xia-Shang-Zhou Chronology Project funded by the Chinese state to ascertain the dates and locations of the first dynasties of China. In Lee’s analysis, the main problem was the relationship between archaeology and historiography. He argues that archaeological data becomes a tool to verify historical records. Note that Chinese scholars have been weeding out unverified Chinese texts. However, the dominant framework for analysis would make these sites easy to fit the findings in a state development model (as well as the reverse, that we interpret these sites as egalitarian). Given our comparative approach to other similar sites, we may be able to parse some features of these urban centres to find evidence of palaces, temple cities, or hybrid egalitarian bureaucracies like in Mesopotamia or the Indus Valley.

Taosi in modern Shanxi Province, was part of the Chronology Project and believed to be the capital of the Xia Dynasty based on historical references. Based on the carbon dating and ceramic typology

It is a large enclosed and fortified settlement of about 300 hectares with:

Royal Palace and an ice storage within the complex

Royal cemeteries

Elite and commoner residences surrounding the palace

Storage centres

Specialised craft production areas

Round-Up

What I do appreciate is the strong religious component in the analysis that has been missing in most of our archaeological interpretation. Luckily, the sites have numerous burial sites and grave goods that we can use to corroborate or propose new readings. That’s what makes this post fun. We have a lot of evidence we can go through and much of the analysis will be contrary to what has been interpreted.