Slow Read Book Club: Chapter 8 (Part 3) of The Dawn of Everything by David Graeber and David Wengrow

The end of egalitarianism in Early Mesopotamia and Anatolia

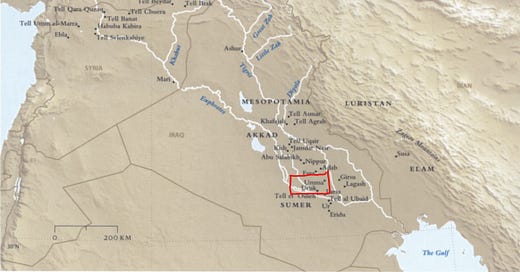

We continue our search in ancient Mesopotamia, roughly the short time period of 3300 - 2000 BC, for egalitarianism. We have two urban settlements develop a centralised form of authority and bureaucracy but with a limited authoritarian government. One city, Uruk, is in Southern Mesopotamia and the other is in the North at the headwaters of the Euphrates River in the Taurus mountains in Anatolia, Arslantepe.

Both began as populated temple-based settlements with a type of centralised bureaucracy that predated the monarchy or an authoritarian ruler. This system would not last. But how is population rule possible without a monarchic autocratic rule? Both had religious affiliations that influenced the everyday life of the settlers to transform them into citizens. While we need more evidence, we can see some clues that point to ancient forms of democratic governance.

Understanding the timeline

The Mesopotamia and the Anatolia regions comprise of multiple small and large settlements that are in constant flux. It is confusing for new learners of the region. The sites have been occupied continuously by different groups of semi-permanent settlers, seasonal nomads, but also conquerors. Therefore, the specific timeline that we are looking at is so short (several thousands of years) with clues so limited by the archaeological residential site and cuneiform tablet records for Uruk. Arslantepe did not adopt cuneiform. My knowledge is, of course, cursory, given the limited time. I am focusing on the period that David Graeber and David Wengrow characterise as centralised, yet, egalitarian urban settlements.

A religious city with democratic ideals?

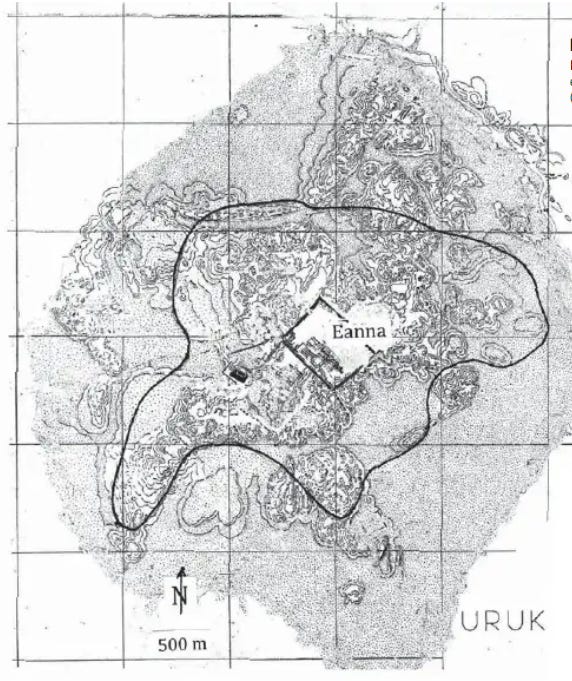

Uruk is a 200-hectare settlement dated 3,300 BC that was continuously occupied until Alexander the Great in the 4th century BC. The population was estimated to be between 20,000 to 50,000. Between the years 4,000 - 3,001 BC (fourth millennium), a public district called Eanna House of Heaven was erected.

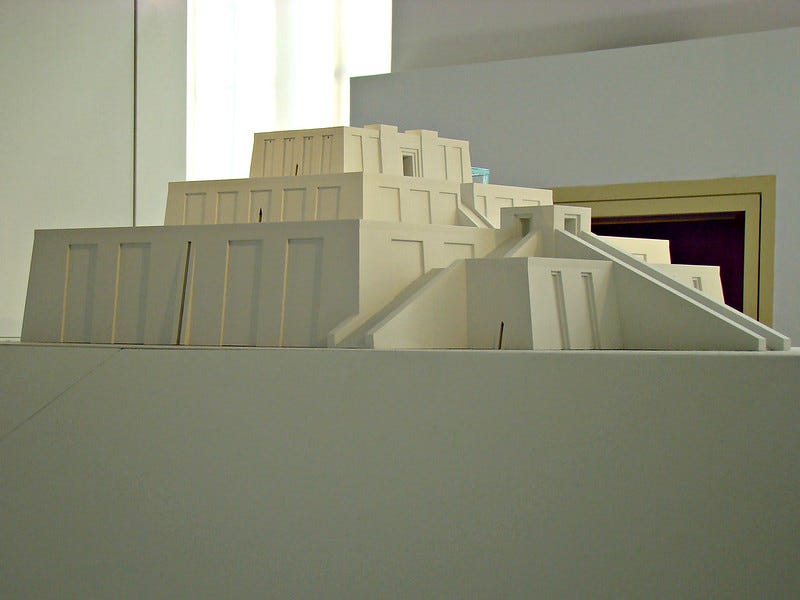

The central temple of Uruk combined both a worship place for the Goddess Ea-nna and courtyards that could be open for the general population for both religious events and pragmatic governance and production activities.

This urban design for a large people assembly venue was what convinced Graeber and Wengrow that the city was governed by the local citizens. They describe the monumental complex as having nine limestone buildings topped with the timbers transported downriver from Syria. The Great Court is an enormous sunken plaza that is 165 feet across and surrounded by two tiered benches and gardens fed with water canals. A part of their argument draw parallels to a similar structure in ancient Greece, the Pynx, that could hold councils for 6,000 to 12,000 people at a time. Much of this is, of course, speculation.

What is true is that these public areas double as food production, processing, and redistribution. The centralised bureaucracy driving the city rests on both the religious/symbolic representation with the pragmatic features of governance. The cult of Ea-nna requires continuous production of food and work/labour to maintain a constant and consistent supply for the Goddess, her cult, and her festivals. Much of the clay tablet records show different standardised measurements of goods develop as well as meticulous records of labour time from people who contributed to its production. It is unclear who these people were - whether they were slaves or corvee labour or indigents who require the security of the temple to sustain themselves. While the temple complex operates in a centralised bureaucratic manner, there is little evidence of a king or monarchic rule. However, the influence of Uruk “exported” much of these standards and culture in the neighbouring and far-flung areas through their trading networks. Uruk became a prized target for conquest.

By about 3,000 BC, the Ea-anna temple was razed to the ground and enclosed spaces were created in the form of gates and ziggurats by conquerors.

Hundreds of years later in 2,900 BC, royal palaces were erected near the temple. It is clear that a new form of governance has emerged and replaced what was previously probably more open to the public. Graeber and Wengrow note that few ordinary settlements are yet to be studied to draw stronger conclusions on elite and ordinary citizens.

Arslantepe and the fall of egalitarianism?

A similar fate befell another central settlement in the highlands of Anatolia (Turkey), Arslantepe. Some scholars believe it to be an outpost modeled after Uruk. Others like Marcella Frangipane (2019) believe it to be less an Uruk colonial outpost but a state on its own. (She introduces the term state here which will be our later topic). One of the significance of Arslantepe is the presence of a temple complex and a bureaucratic administration without monarchic rule. This is why it appears to be a sister city of Uruk in the North. But with no written records, it is hard to deduce its similarity.

Arslantepe is important and highly prized for its metal, metallurgical skills of its residents, and timber resources. It sits in the Malatya Plain located 3,300 feet above sea level and was most likely snowed in during the winter period. It is in the neighboring Elazığ province and within the Taurus Mountain zones.

Arslantepe during the 3800 - 3400 cal. BC appears to be similar to other Tepe in the region with small room housing, typical houseburials, and ordinary grave goods such as cooking pots or bowls. However, there were elite housing that consisted of subdivided rooms from a large hall with white plastered mudbrick colums. Southwest of this housing is Temple C.

Just like the Eanna complex, Temple C functions both as religious and secular centres including food production and redistribution. The large room measures 18 x 7.20 meters with a wide platform at the centre for meals as part of the ritual practices. There was areas for food storage but unlike Uruk, had no system of writing or recording. Nevertheless, Frangipane agrees that Arslantepe is similar to its Mesopotamian counterparts in terms of bureaucratic governance to supply the temple complex.

Between 3,350 to 3,000 BC, Temple C was replaced by a more restricted and enclosed design access in the form of Temple A and B.

However, by around 3,000 BC a fire destroyed the palace temple and the period until 2,800 BC marked a period of instability and conflict before it was completely abandoned. What happened? The record is unclear. However, what appeared afterward in the archaeological record show a shift in culture and governance model. Frangipane theorise nomads and pastoralists occupied the abandoned Arslantepe and brought a Transcaucasian culture or people from the Caucasus and Armenian highlands.

The result is a fortified acropolis in the upper settlement for unknown reasons. The village occupys the mound slope and maintained household production of metallurgy, cereal processing, and a courtyard for livestock slaughter. Outside of the village walls, there is one elite burial consisting of a male with jewelry and gold silver ornaments and swords. He was buried with two young presumably slave children found on top of his tombstone and two household servants outside of the cist or coffin-box. The disappearance of the cult areas, mass produced bowls, elite burial, and fortifcation made Frangipane interpret the shift of Arslantepe towards a military leadership with defense as its primary objective rather than bureaucratic governance. This is why Graeber and Wengrow suspect that a warrior society has taken over Arslantepe.

Round-Up

We have two examples of a small and large urban settlement with two key features of democratic governance: a combined religious and pragmatic centralised bureaucracy. These two major factors enabled a size like Uruk or Arslantepe to operate without a clear elite monarchic rule despite some evidence of elite housing or differentiated individuals. Still, in Uruk, there is no recorded mention of a king.

I would almost agree that there is a shift in urban design that indicate enclosed and exclusive access to religious spaces and the reduction of public assembly spaces. Especially in Arslantepe. In both cities, elites do exist but it does not seem to have much impact in governance until changes to temple practices have dissolved potentially its link to public assemblies, participation, and governance. This does not bode well for the citizenry with the lack of large religious and public participation in the city’s daily activities.

It is no surprise that the egalitarian or democratic governance of bureaucracy was ultimately replaced by those who seek to conquer. As we have seen in the Late Neolithic, both egalitarian-based and warrior-based societies, co-exist. The time of egalitarianism has ended and now it is the time of kings.