Slow Read Book Club: Chapter 8 (Part 2) The Dawn of Humanity by David Graeber and David Wengrow

Freedom in Early Mesopotamia

Freedom with scale and bureaucracy

In part two of our case studies for egalitarian urban cities, Early Mesopotamia provides an example of scale and bureaucracy without sacrificing citizen autonomy or individual freedom in the political arena. Or so what Graeber and Wengrow believe. They largely focus on evidence of political assemblies, people councils, and the participation of women in civic life as hallmarks of not just freedom but also of a form of egalitarianism at scale. The idea that Mesopotamia possessed a ‘primitive democracy’ was first advanced in the 1940s by Thorkild Jacobsen, the Danish historian and Assyriologist. Graeber and Wengrow disagreed with the label of primitive democracy because it assumes that it is not complex when, in fact, they are.

Early Mesopotamia

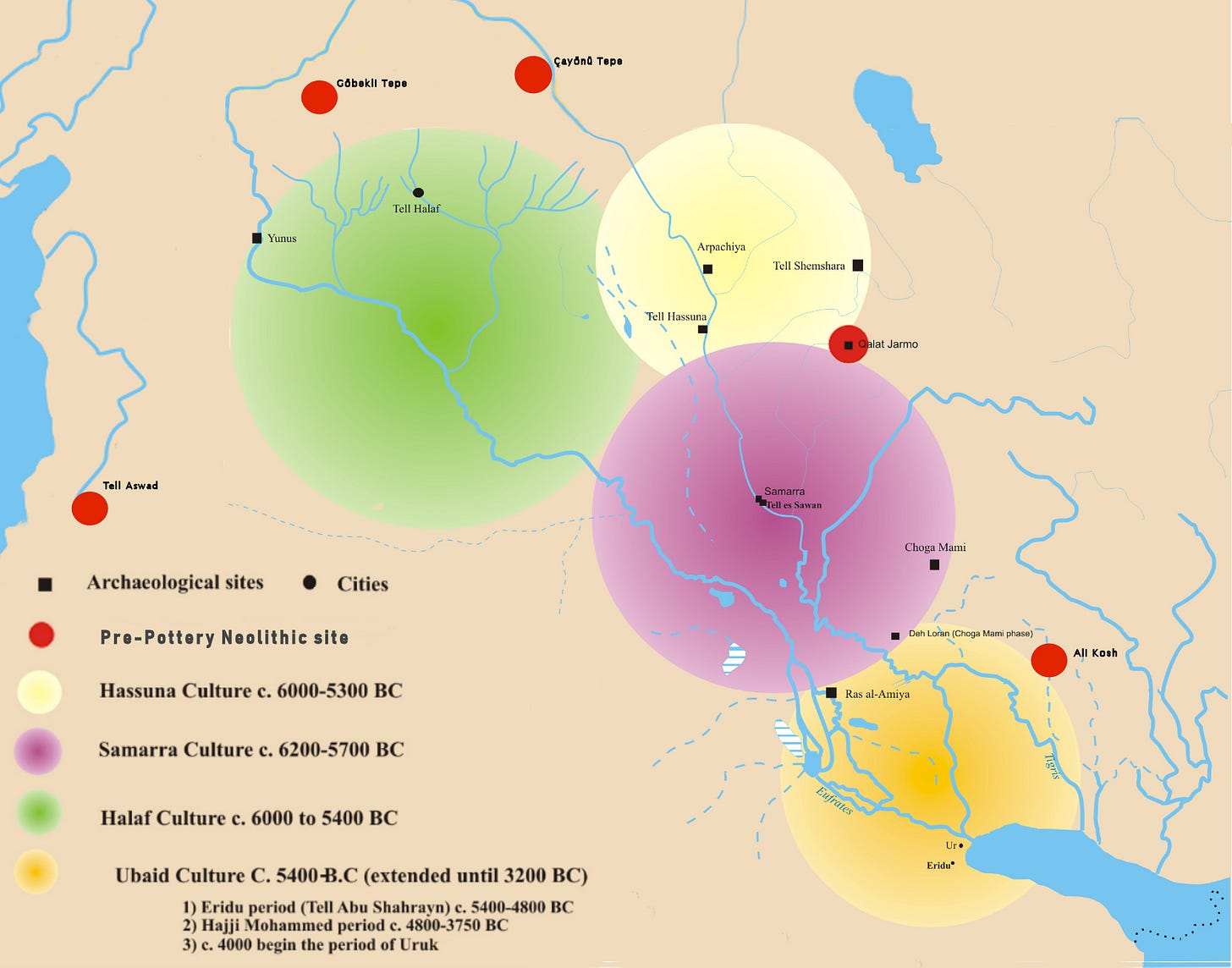

What we know as Mesopotamia is actually South Mesopotamia, situated in the alluvial plains of the Tigris and Euphrates plain. North Mesopotamia consists of the areas between the Zagros Mountains, the Anatolian plateau, and the Euphrates River at Carchemish (modern-day location as Karkamis in Turkey and Jarabulus in Syria). If you trace this area with your finger, you will form a crescent covering the North and West (Mediterranean) all the way to the South (Persian Gulf).

The evidence we know about the political assemblies is set in the time period 3,000 - 1500 BC.1 Prior to this period, we have yet to find out what happened clearly. However, the development of Neolithic Mesopotamian urban villages like Jormo (7,000 - 4900 BC), the Samarran culture (5500-4800 BC), and Ubaid culture (5500 - 3700 BC) show similarities with other Neolithic egalitarian settlements.

Like Cataholyuk Tepe, these urban settlements have some indications of centralised activities but are otherwise devoid of highly bureaucratic structures.

What allows them freedom is the continued possibility of seasonal movement and escape between the desert (animal herding) and the fertile plains.

People Councils

Several thousand and hundred years later, these egalitarian arrangements came to be found alongside bureaucratic structures with an elite class performing local governance issues like divorce or neighborhood activities. Some of these assemblies are also related to temple administration and related activities. Both these types of arrangements traffic between secular and religious purposes. Note that almost all the information is only available around the second millennium from clay tablets.

To make this system work, we need a sense of identity that is beyond the household level. One is a lineage system and the other is the more interesting city identity that Bojko Barjamovic says is essential to have a functioning council.

The sense of communal affiliation within the city-state rested upon a notion different from kinship. Its population was multi-ethnic, proclaimed no common ancestry, and (like the tribe) it shared its language, religion and culture with a number of other communities…(49)

Why was this system of governance maintained? It acted as a check and balance between those who were in positions of power and the people’s will. The result is a form of indirect control and freedom granted to these urban settlements for local issues. This is why royal envoys would have very little power in these satellite communities.

The linguistic references of people’s councils across different cities and times like in Old Babylonia (1900-1500 BC), the city-state of Assur (see map above), and the council of elders in the poem of Gilgamesh and Agga, among others show that this practice is not unique. This predates what we know of the Grecian origin of democracy. Unfortunately, its ubiquitousness means that much of the protocol is left unrecorded with only the royal or exceptional cases receiving written form.

While there is very little evidence as to how these councils are run, however, there is a trial in Nippur that shows the participation of ordinary citizens as part of an assembly. Here’s a podcast episode detailing the oldest murder case recorded (No, I am not talking about Cain and Abel). The case starts at 17:04 and the mention of the assembly will be at 22:34, and 27:04. The enumeration of names of the assembly is at 29:47. Here’s the audio from the Criminal Records Podcast, Episode 32.

The Mashkan-shapir, the second city of Larsa, had no clear status distinction in their residential neighborhoods and central offices.

The city of Mari, West of the Euphrates (2950 BC - 1760 BC) shows a complex of palaces and royal areas but with no evidence of urban resident settlements. Graeber and Wengrow postulate this as an expression of a population's withdrawal of support to a reigning king.

Round-Up

Early Mesopotamia demonstrates the ubiquity of councils and people’s assembly within hierarchical and warrior models of governance. Democracy’s roots go way back than the Greek attribution but probably due to current political reasons, this was not readily taught.

In part, I believe that Christian text has positioned these Mesopotamian groups - the Sumerians, Hittites, and Babylonians as anti-Christian, ignoring the other features of their culture and governance practices. The Code of Hammurabi does not help project an equitable system. In fact, it is rather odd to have a totalitarian system and the people’s voices operate within the same milieu.

The region is home to political strife which makes research difficult and site destruction, sadly, a reality.

The Islamic influence in popular history narratives is low and therefore much of this information is available only to niche audiences.

The presence of a people’s council though does not mean that egalitarianism remained as what we know from the early Neolithic periods. A hybrid system of democratic local governance units combined with highly centralised and autocratic systems seems to be the Early Mesopotamian model. While I do believe that knowledge of these people’s councils balances out what we know of Mesopotamian city-states, it does not mean that people experienced sustained justice or freedom.

What has changed by this time:

Limited seasonal movement - while the desert and herd animals remain important in the region, much of the population has reduced mobility with resources largely circumscribed around fixed assets like mud homes, nut trees and publicly shared structures like temples or community projects

The gradual erosion of female roles in society - the warrior societies and autocratic system are largely male with art representing more male figures in power

Writing and bureaucracy have ‘fixed’ or standardised some ideas, codes, and rules that would otherwise remain oral and more flexible to interpretation or rejection

A stronger city or place identity has developed

These and other reasons have contributed to the reinterpretation and dilution of egalitarianism within urban settlements.

I have largely omitted the female component of political participation due to time constraints. I hope to have time to discuss it in the next one.

My main source is Jonathan Postgate’s Early Mesopotamia Society and Economy at the Dawn of History. Daniel Fleming’s Democracy’s Ancient Ancestors Mari and the Early Collective Governance is a great read.