Slow Read Book Club: Chapter 11 (Part 2), The Dawn of Humanity by David Graeber and David Wengrow

How the Osage clan and tribe structure is an example of political reform

Hi Readers,

I’ve been away from this book for close to a month already. It may be hard but that is what I am here for. To help you get through the finish line. So we’re nearly at the end. I want to be there with you on that.

Enjoy a peaceful reading holiday,

Melanie

Cycle of State and Anti-State

The only constant in human history since the Paleothic period is the cyclical community building and destruction. That is, as settlement expands, people stifle under increasing social control. (Not surprisingly, environmental collapse too). This becomes a problematic bargain for the sake of community. Thus, revolution, political competition, or total rejection become inevitable and spells the end of a settlement. Nothing lasts forever.

We see this cycle again in Etowah River Valley, encompassing the areas of what is now Georgia and Tennessee. The ancestors of the Choctaw built small towns along the river around the same period as the Cahokia (1000 AD - 1200 AD). These eventually escalated into palatial mounds, tombs, and palaces. At which point, by about 1375 AD, unknown internal or external enemies, sacked Etowah’s holy areas. There were attempts to occupy the area again but was ultimately abandoned possibly for lack of ritual authority or economic resources.

What happened during the contact period?

Graeber and Wengrow argue that by the seventeenth and eighteenth century, North American Indians were in the middle of political and cultural reorganisation. This is contrary to the accepted reasons that community collapse occurred due to war, slavery, disease or conquest. Rather, the authors argue that communities rejected the highly hierarchical societies around the mound structures (seen in South American societies), embraced smaller community sizes (about 1,000 to 2,000), and established egalitarian clan structures and communal councils. According to the authors, there was a political war over hereditary forms of leadership and elite knowledge hoarding. This meant that a lot of mound-based hierarchical societies were eventually eliminated (including stories about it) and in its place, the institution of consensus building council houses ensued.

We circle back to Kandiaronk and the practice of long debates around tobacco (smoking pipes) or caffeinated drinks akin to a coffee houses of Europe by First Nations groups. This has come to replace the hierarchical model with the mound- based cultures eliminated though always in tension with the egalitarian model.

How the Osage Got Out of Coercive Structures

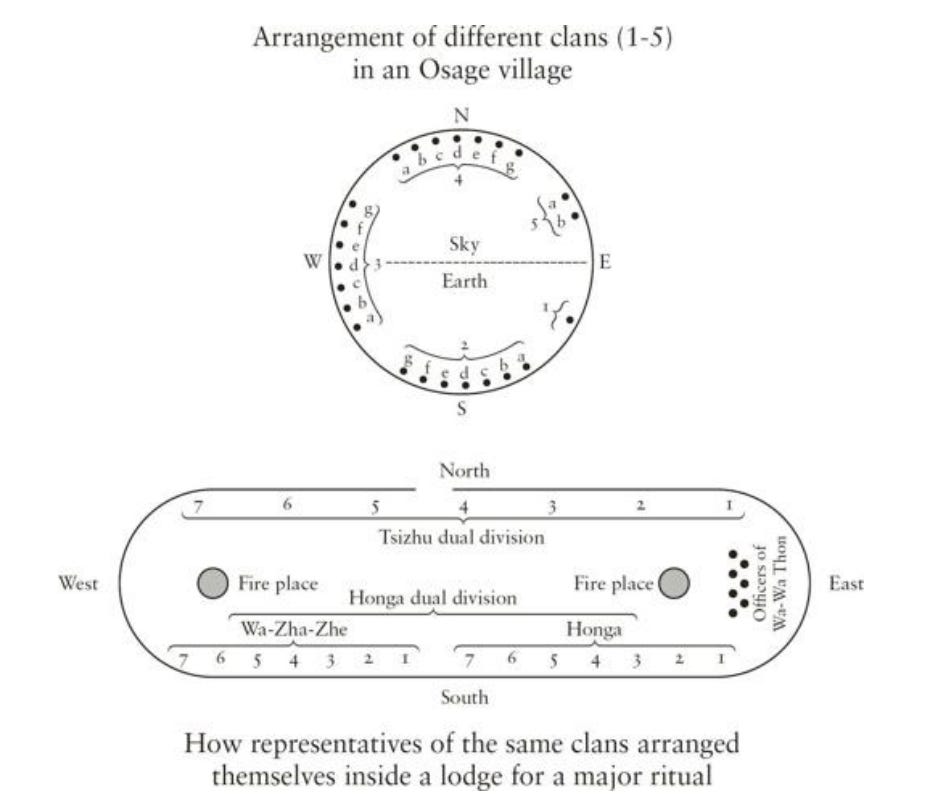

An example of the cultural and political re-orientation is the Osage clan who can trace their ancestry direct from the Mississippian Fort culture and who were able to ally with the French government and maintain a somewhat independent status. They were free to trade and established their own empire between the periods of 1678 to 1803. Moreover, their story was recorded by Omahan speaking ethnographer, Minxa’ska (Francis La Flesche).

In his description, Minxa’ska describes how the Osage elders reorganised themselves into twenty four clans divided into Sky, Earth, and Water with the latter two part of the earth moiety (a term referring to the social division of a single clan into two halves. The Earth and Water clans may be divided but trace their descent from a single ancestor).

The unique division of Osage society means that esoteric knowledge, political and origin knowledge, is divided across clans and everyone has access to a part of it. The very nature of their story or myth is enacted in their clan structure, that is, the nature force (God or Mystery or Wakonda) stems from the interaction between Sky and Earth and so their marriage rules involve one group marrying into another. Their village order or circular organisation follows from their mythical constitution that subvert centralisation.

This type of social knowledge is attained or understood at a lower level by most people. However, those who advance into the knowledge level are known as the Nohozinga or Little Old Men who can discuss natural philosophy and negotiate with political authorities.

Graeber and Wengrow argue that North American First Nations were the leading thinkers and doers of Enlightenment principles around institutional reform. They argue that this comes much earlier than the widely recognised source French philosopher Charles Louis de Secondat, Baron of Montesquieu (Spirit of Law published in 1748). They postulate that the Baron garnered his ideas from a public event held around 1725 when French explorer Bourgmont brought Osage and Missouria delegation from the Atlantic to Paris (including his son named Missouria). They surmise that the Baron would have gotten some ideas from them.

We return again to the early argument from Graeber and Wengrow about the importance of the North American example to their state formation thesis. That is, even if coercive societal formations occur, like in Cahokia or Etowa, there is a way out.

The Paradox Remains

What is important in the authors’ extensive discussion of egalitarian reorganisation in North American First Nations is that a paradox exists. That is, there is tension in any human group. The desire to dominate another needs to be checked.

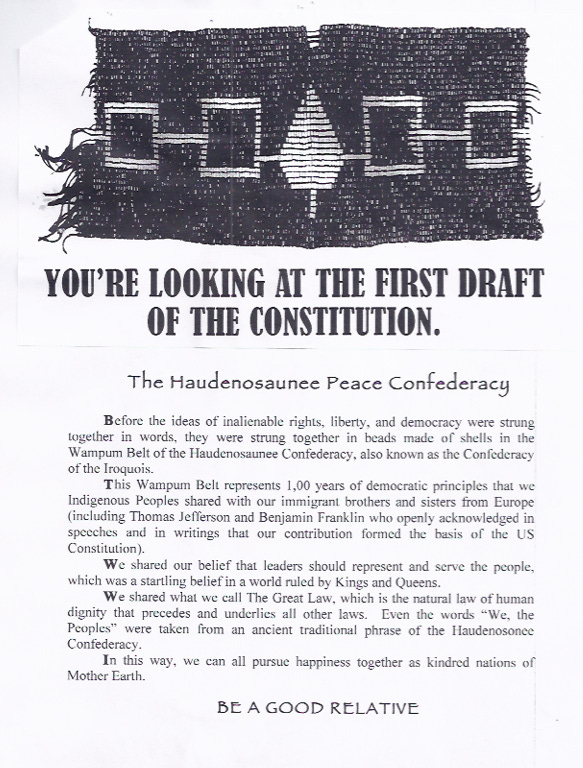

Thus, one important resource available is the foundation document of the League of Five Nations around Late Ontario (the Seneca, Oneida, Onondaga, Cayuga, and Mohawk), called Gayanashagowa. It is a political confederation document infused with mythical characters of a Peacemaker and a Mother Figure that aims to install order among warring factions but also envision how human relations are conceived by recording them alongside episodes of crises.

The league is said to be created between the years 1142 AD - 1650 AD. The origin story elements include narration of crises: warfare and torture in the year 1050 AD, recording of new crops: corn, beans, and squash, the formation of settlements as large as 2,000 inhabitants and the control of population thereof according to limits to game and hunting. Most importantly, the figure of the Mother of Nations, the Jigonsaseh, is important as a creation but also a historical figure in which female councils balanced the male-led councils and warriors.

Round-Up

We circle back to the Indigenous Critique of Western Society to highlight the ways in which nations or confederacies are envisioned. This is why the North American First Nations are important historical institutional processes because:

They actively rejected the hierarchical political and social model of the mound culture or pyramid building culture (as its counterpart in South America)

They actively sought to rebuild different socio-political ways to ensure egalitarian processes using a combination of small group sizes, mobility, generalised access to esoteric knowledge, and female participation.

Graeber and Wengrow argue that while birth and destruction of human communities are part of the condition, this means that the state as a way of life and system as we know it is NOT inevitable. The case of the First Nations show how we can reconceptualise a vision for order that supports egalitarianism as a way of life.

Our follow up questions could then be:

How do we manage this when human populations are now in the billions? And we live in mega cities? Should we focus on neighbourhoods?

How do we ensure adequate food resources from both staple and wild ones?

How do never forget human crises and from there create shared myths or vision of community?

We have long ignored the contribution of the First Nations to our political philosophy and the authors’ work is one way to make First Nations’ fragmented stories comprehensible if we want to rebuild an anti-state.

I’ll see you in the final chapter. I am excited to start a new book in 2024!