Slow Read Book Club: Chapter 11 (Part 1), The Dawn of Humanity by David Graeber and David Wengrow

Are we doomed to end up where we are now?

The state as the conclusion of human development?

I’m probably not the only person to think that if we did not have the West go on around the world, conquering people, surely, someone else would have done the same thing.

We will end up in the same system we know now, except with different players. We could be speaking any one of the Native American languages, German, Japanese, or even one of the Aztec languages by now.

Why is this idea tempting and is this right?

In short, Graeber and Wengrow expectedly, disagree. They argue that the idea of the state as the inevitable outcome is an insidious product of the predominant Western-based social evolutionary theory. While they have argued previously that democracy may be a product of the indigenous critique, the concept of evolutionism is not.

Evolutionism is what they saw as a way for European writers of the eighteenth century to classify human societies according to different means - subsistence, technology, or power. Evolutionism goes against our complexity-to-complexity model and instead enshrines the simple to complex ranking of society with an apex elite managing at the top.

Pernicious evolutionism

We have read different versions of an evolutionary framework:

By technology - hunting, pastoralism, agriculture, industrial civilisation

Anthropology - Lewis Henry Morgan’s savagery, barbarism to civilisation

Marxists focused on power - primitive communism, slavery, feudalism, capitalism, socialism, communism

Evolutionary thinking is a hard disease to get rid of without alternatives. The prevailing mode we tend to classify human societies and interpret ancient finds are the following:

Band - smallest and said to be simplest consisting of mobile groups without political roles or extensive division of labour like the !Kung

Tribes - horticulturalists, informal sources of power with totemic clans or lineages; they might be slightly larger but their importance would be the same; groups like the Nuer fall here

Chiefdoms - ranking appears with craft and ritual specialists and some surplus evident with the chiefs fulfilling a redistributive role to the residents; Calusa of Florida and Natchez can fall under here

States - three key features we have previously discussed: use of violence, bureaucracy, division of labour, and the addition of agriculture

Not all groups can fit here and that is the problem. Not only does this force us to fine-tune the model to fit the data, but we also miss out on the dynamic of the different components within the categories as it appears in other societies.

True comparison: North American states

One way out of it is via comparison. While the authors don’t do a very good job explaining how this can be done, they do point out that people from North America provide a good control example of what possible outcomes look like. This is because the North American continent largely remained insulated to a certain extent from developments in the Eurasian continent until colonisation in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.

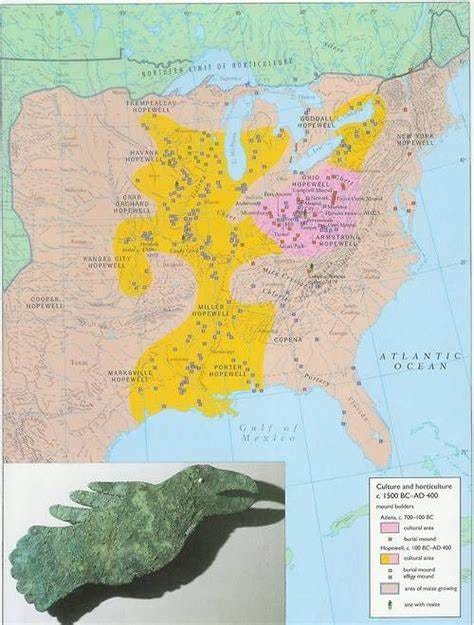

Let’s see what we can learn about two of them: the Hopewell and the Mississippian Valley Cultures.

Hopewell Culture Area

We need not go to Mexico to see North America’s early urban settlements. A network of settlements called the Hopewell Interaction Sphere (100 BC - AD 500) was built along the Ohio River Valleys. These are communities that participated in some form of hard-to-determine ritual complex. How did we know?

They deposited copious quantities of goods under burial mounds - some include obsidian from Appalachia, copper from the Great Lakes, conch shells from the Gulf of Mexico among others

The buried materials seem to be used to build ritual paraphernalia and costumes

Construction of giant earthworks may be systems of measurement linked to astronomical meanings or it could be a by-product of creating flat spaces for games, feasts, and assemblies

The larger earthworks such as Poverty Point or the Newark Earthworks in Licking County, Ohio have a much more deliberate construction. The Newark is said to be a lunar observatory set over two square miles with embankments as high as sixteen feet tall

The basis of measurement for these sites is made by arranging cords into equilateral triangles. This system of measure marks other Hopewell sites in the upper and lower Ohio Valley. It appears that for much of the period, these sites remain empty and people only congregate at specific times of the year for games or ceremonies.

The rest of the time, it appears that people preferred to move around, hunt, and plant garden plots with North American staples like sunflowers, goosefoot, sumpweed, and squashes and live in homestead arrangements. They mostly chose to live on higher ground and dispersed with no single city centre. There is no definitive explanation for the multiple mound sites. One of the prevailing explanations was that people visited different sites to fulfill a ceremonial cycle.

Now, if we classify Hopewell as a North American state because of the megastructure then other features do not seem to fit.

Lack of a bureaucracy - Hopewell’s art relies on individual differences rather than standardisation that you would likely see in an expansive cultural area

Lack of total domination over the people

Lack of violent indicators

Hopewell influence on the Native American communities focuses on what Graeber and Wengrow label as ritual diplomacy around the seasonal aggregation of strangers. Hopewell burials end around AD 400. Graeber and Wengrow believe that the purpose of these mounds uniting a broad swathe of people under a common rubric of ritual diplomacy may have been fulfilled by that time.

The State of Cahokia of Mississippi

Following the conclusion of the Hopewell sites, settlements along the Mississippi Valley between AD 400 - 800 emerged. Cahokia sits on what is called the American Bottom, a place of swamp, shallow pools, and mud. It is no surprise that the largest mound was constructed there to connect to the underworld.

The Monk’s Mound sits in the background of a wide plaza and is a vantage point for the ruling elite looking over the planned residential zone. Some of the mounds have palaces, temples, or sweat lodges atop them. Other areas of the place had spaces for visitors or foreign populations and craft specialists. By around AD 1050, the population would explode up to 10,000, some estimates totaling 40,000 in the American Bottom.

Cahokia conducted mass executions and noble burials in the early stages of its growth. It required human sacrifice for elite burials and the exercise of violence to maintain this esoteric structure. This violent component of governance meant that few self-governing communities would remain in Cahokia hinterlands.

This forcible aggregation of communities under elite surveillance also applied to games. Reminiscent of the Mesoamerican ball games, chunkey was invented around AD 600 in Cahokia and attracted spectators. The objective is to throw the spear as close to the rolling ball disc without touching it. The winner is the one who is closest to the disc once it stops rolling.

The game eventually became an elite monopoly with the chunkey discs disappearing in ordinary burials and appearing in rich graves. Despite this, it was an important avenue for commoners to become nobles and enshrined in bird-man symbolism.

Compared to Hopewell, it seemed Cahokia had the markers of a true North American state similar to developments in Mesoamerica:

Extensive esoteric knowledge embedded within burial mound technology and funerary rites and grave goods

Ritual and physical domination of certain sectors of the population - human sacrifice in elite funerary burials

Growing elite groups or selected individuals - via competition

As we can see, the categories of state do not completely satisfy Cahokia but you can see its connection with its Mesoamerican counterparts.

From State to an Anti-State

The experiment of the state would not last very long. In AD 1150, Cahokia erected a palisade around parts of the city due to external threats and destruction from its neighbours. War, destruction, and abandonment would prevail in Cahokia with the state system being rejected and across its regions. After AD 1400, the region would be referred to in the literature as The Empty Quarter with no resettlement or reuse of these areas again.

What we find in the Mississippi Valley region consists of several features shared with other Eurasian settlements:

The reverse process - state-like features and urban aggregation collapsing into smaller dispersed groups

Cultural refusal of the people for long-term dependency or domination and abandonment as a direct response

Lack of total power of elites for full total domination

It is unfortunate that there is so little mainstream interest and awareness to connect these North American groups and archaeological sites to the discussion of statehood and the fate of human history. Most of the sites have been destroyed by development partly because the mounds were…not impressive by any means compared to their Mesoamerican cousins.

By the time the French, Spanish, and British encountered the Mississippian Valley cultures, they were already done with the state experiment. They have already chosen to be smaller polities that attempted to maintain egalitarianism.

Round-Up

Using the North American examples, the state nor a monarchial system is not the penultimate human conclusion. We have seen that the social evolutionary framework does not fit the dynamics that happen to experiments in human society.

It is clear that an elite system combined with esoteric knowledge may result in increasing use of violence

It is difficult to achieve total domination over people across territories in the absence of a bureaucracy

Abandonment and war are necessary forces to counter pernicious surveillance and unequal systems

It is possible to do a system reset after several hundred years of the status quo.

In part 2, we shall learn how the Native American Indians did it.