Slow Read Book Club: Chapter 10 (Part 2): The Dawn of Humanity by David Graeber and David Wengrow

In our last post, I posed some provocations about the use of the term ‘state:’

What do we lose by using the term ‘state’ to describe settlements?

We lose the unique and interesting things that may have occurred that do not fit the term or by trying to fit settlements into the term.

What do we have in common and what differences do we have between past settlements?

When it comes to historical constraints, it seems that a ‘state’ revolves around the exercise of sovereignty, bureaucracy, and competitive politics. The variation revolves around how much these are present or absent in any polity.

What can we learn about the ‘state’ and freedom and equality?

Graeber and Wengrow talked about the three freedoms that we can see throughout human history: the freedom to move (mobility), the freedom to disobey (rights of refusal), and the freedom to create and transform social relationships (that is, free from bondage under another person or system that erases our kin rights). It is apparent that the ‘state’ has perverted or circumscribed most of these freedoms into full domination or control.

And this is where we start: when we lose our freedoms.

Why we recognise Egypt as the proto-state

Graeber and Wengrow propose that we see similarities with ours because it appeared that (pre) Dynastic Egypt emerged as

a combination of exceptional violence and the creation of a complex social machine, all ostensibly devoted to acts of care and devotion.

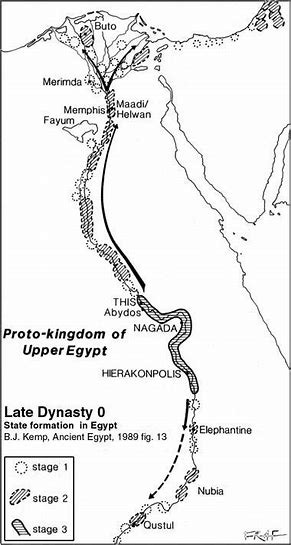

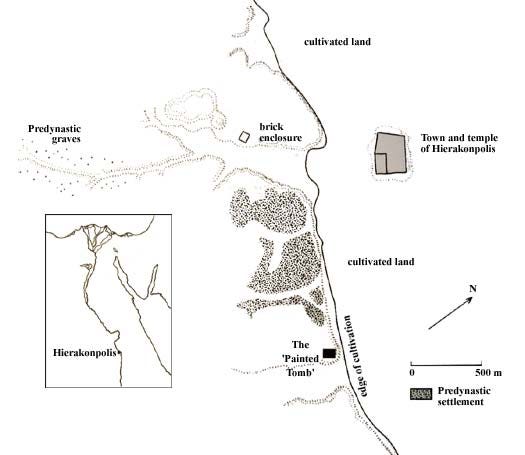

Prior to what we recognise as the monarchial kingdoms in Dynastic Egypt, the early sites (4,000 - 3,100 BC) were small kingdoms with multiple burials of monarchs extending from Naqada, Abydos, Hierakonpolis to Qustul in Lower Nubia.

There was evidence of multiple gravesites with a variety of grave goods comprising humans and animals.

Graeber and Wengrow postulate that the evolution toward monarchial kingdoms stems from what they call a combination of agronomic and ceremonial processes. For Egyptians, they traced it to their specific belief that the dead become hungry and need to be fed leavened bread and fermented wheat beer. This need started the creation of what they see as the first peasants who became tied in debt and obligation to fulfill these requirements, especially those without means of arable land, oxen, or plow. By the time the First Dynasty rolled around, estates were created to fulfill the needs of the dead including the creation of the Great Pyramids (2500 BC) but also bread and beer to supply workers during their seasonal royal construction projects. Temporarily, they become relatives and caregivers to the king and well-fed.

The model of the monarchy seems to be a popular adaptation in human history and mostly they theorise it as combining caring for a baby with the terror of the monarch’s power to wield mass violence. We have both sovereignty and administration but with the absence of competitive politics.

State as a family and a machine

The observation of Graeber and Wengrow about the state as a tool for care but also of terror is significant.

When sovereignty first expands to become the general organizing principle of a society, it is by turning violence into kinship.

This explains the practice of ritual killing around royal burials in which subjects are incorporated as part of the royal household since they care for the king.

…a ritual designed to produce kinship becomes a method of producing kingship.

They posit the idea that caring labour is a particular task tending to the unique qualities and needs of the cared for. The state usurps this principle of care but corrupts it with ‘a confluence of maths and violence.’ When a state and bureaucracy combine, it results in total domination, and the appearance of slavery and bondage.

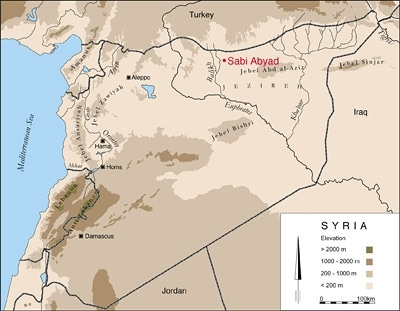

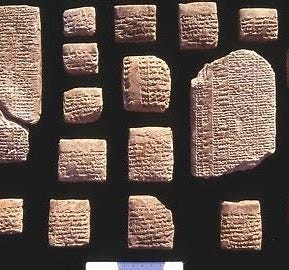

However, as we have seen previously, the appearance of a bureaucracy did not correlate with a large ‘state’ but with smaller communities like Tell Sabi Abyad in Raqqa, Syria (6,200 BC).

The site is remarkable for its record-keeping rigor prior to writing. The village had central granaries and warehouses tracked by using geometric clay tokens, seals with stamps, and identifying marks.

Unlike common assumptions, the village bureaucracy has an absence of large residences, rich burials, and personal status. Rather, their bureaucracy seemed to produce standards of uniformity like those found in cities. (Note: cities won’t appear until 2,000 years later in Mesopotamia.) Bureaucracies seemed to prevent rather than produce hierarchy. However, such measures of tracking and care can be used for nefarious reasons and produce suffering.

This was what happened with the ayllu system of the Inca which was a way to allocate land and labour to ensure that everyone met their needs and provided mutual aid at the village level. They used khipu strings to track (tying) and cancel debts (untying). Once the bureaucracy of the Inca state was overlaid on top of it, debts were never untied producing a host of peons for the Incan courts which the Spanish exploited.

What’s interesting is their observation that

…the most violent inequalities seem to arise…from such fictions of legal equality.

Bureaucracy makes this possible with what they call principles of impersonal equivalence. Equality is made on the basis of interchangeability, or erasing personal differences that would be unlike if issues were discussed on a personal level. Hence, if we think about it, the origins of inequality ride on the back of equality. It is two sides of the same coin.

The modern state

This leads us to the main argument of Graeber and Wengrow that the modern state as we know now is just one form arising from three different principles: sovereignty, bureaucracy, and charismatic competition. All three of which, by themselves, have different origins. We’ve merely moved from the power of kings to the ‘people’ (nation) for the benefit of the people but competitive elections we now call ‘democracy.’ Quite a scathing critique but one that I nod and agree with. With the breakdown of sovereignties and bureaucracies, they call on us to rethink political governance and the possibilities afforded by decoupling what we think of state, bureaucracy, and power.

Back to civilisation

If we are to rethink political governance, we probably need to return to the etymology of the Latin civilis,

political wisdom and mutual aid that permit societies to organise themselves through voluntary coalition.

This is far from what we understand civilisation as referring to deeply stratified societies, an authoritarian government, and the subordination of women.

Throughout my previous posts, we have looked at the nature of equality, and this has been rooted in women’s work in small communities. At some point, there was a sudden shift to a patriarchial system. They argue that this is a gender appropriation of what was once women’s work - such as weaving and beadwork, and converted to geometry and calculus.

One such civilisation that they believe to be based on female political rule is Minoan Crete. A theocracy ruled by a councilor of priestesses. They support it by interpretations of art that focus on the ‘sexual energies and spiritual epiphanies.’ The throne rooms had bathing chambers until archaeologists found one under a fresco depicting female initiation linked to menstruation.

The point is that these ancient sites provide us with social and political possibilities that we ignore by labeling them ‘state’ or non-state.

Round-Up

The definition of a ‘state’ requires three features:

sovereignty

bureaucracy

competitive politics

Of course, proto-states are defined, as pre-dynastic Egypt, because they do not have three of these features. In fact, much of ancient societies have varying degrees of these. This means that these features evolved independently from each other.

When it comes to the origin of equality, Graeber and Wengrow postulate that it is two sides of the same coin with inequality. Their example is the nature of bureaucracy, originally thought of as a means to give aid to the locals. The ayllu is one such example:

uses the khipu, knotting technology, to allocate labour and resources to families

reduce marked economic and social differences among households

This same means to help others was used by the Incan court to produce unchanging economic states of people creating peons and slaves.

The challenge is to return to the core feature of society, that is, rendering mutual aid cognizant of changing individual circumstances, a civilisation. And we have a growing number of examples in our ancient past to lead the way.