Slow Read Book Club: Chapter 1 - On the Experience of Moral Confusion, Debt the First 5,000 Years by David Graeber

Untangling debt, morality, and violence in contemporary times

Reading David Graeber

I admire the ambition of Graeber in asking the Big Questions relevant to both academic and mainstream audiences in an accessible writing style. However, as I have previously mentioned in reading The Dawn of Everything, he writes as he speaks. That means there are gaping flaws. While his language is simple, his arguments stack, branch in multiple ways, and meander in different directions. Sometimes, you feel you have grasped his argument…then it floats away. He presents interesting insights that appear to answer his questions, but indirectly. This leaves you with a sense that maybe he answered one question but not what he started with.

I feel unhinged, in awe, and confused at times.

What helps is the act of writing as a device to think. Dear reader, as we spend the year together, I hope to extract his insights and be better thinkers.

The power of debt

Why write about debt? Graeber believes that debt as a concept is poorly understood and obtuse. Herein lies its power. Graeber argues that debt encompasses social relations built on different levels and scales of violence (at the social to the institutional and state levels) that imbues debt as a moral obligation. Hence, he talks about insidious social practices that appear acceptable but are actually unjust, ridiculous, and preposterous. And yet, we all seem to subscribe to the idea that all debts must be paid.

How did this come to be?

First circle: The principle of social obligation

Social obligations define our social world and Graeber argues that we tend to see obligations as debts — one that needs to be repaid. This moral aspect, defined by the Oxford English Dictionary, becomes part of the accepted social standards for what is good and right. This is what he says is the first level of confusion that debt accrues. It presents a conundrum:

Repaying money owed is deemed moral (even as it results in poverty, suffering, bondage, death, or destitution)

Take the case of the low caste in the Tehri Garhwal in the Eastern Himalayas wherein as late as in the 1970s where Jean-Claude Galey documented debt bondage. In their situation, low-caste individuals incur debts for weddings and funerals to higher-ranked caste members. The collateral in the case of a wedding is the bride herself. She becomes a concubine for a few months and works for the creditor’s family for several years until it is paid off. It is only then that she can continue her life as a married woman. Though it sounds shocking, it is not perceived as unjust. Furthermore, the moral authorities here, the Brahmins, are usually the moneylenders.

Morality as it appears here and in other groups is encoded in cultural norms.

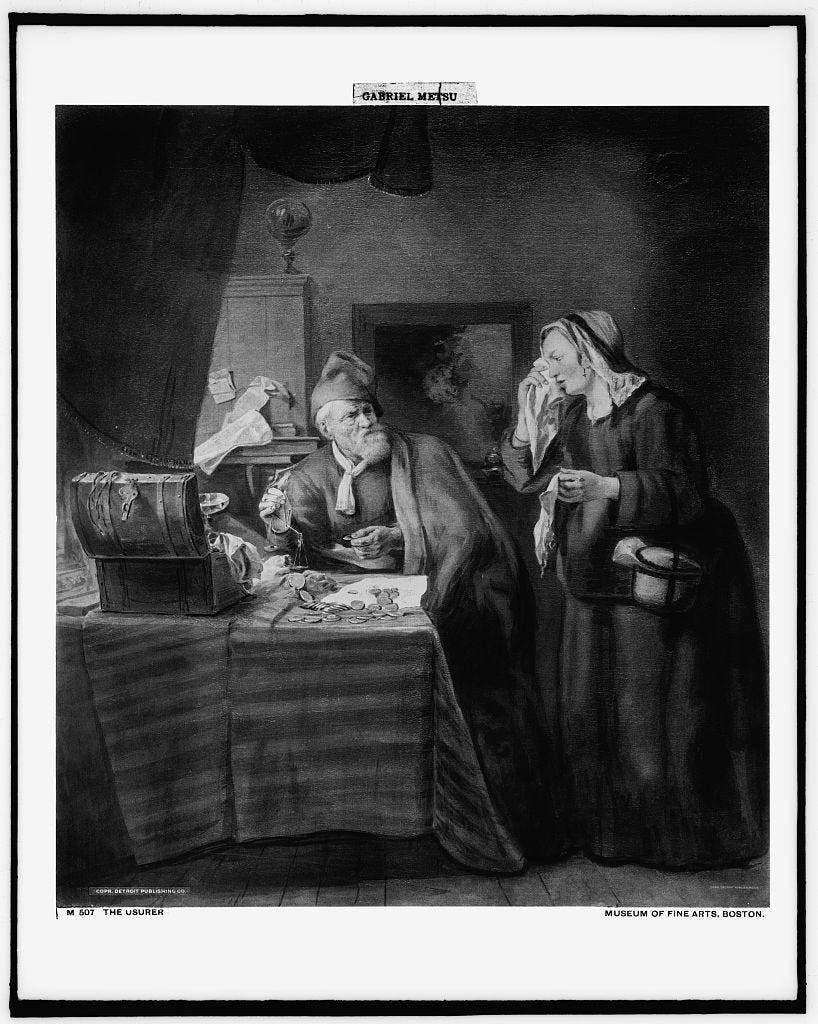

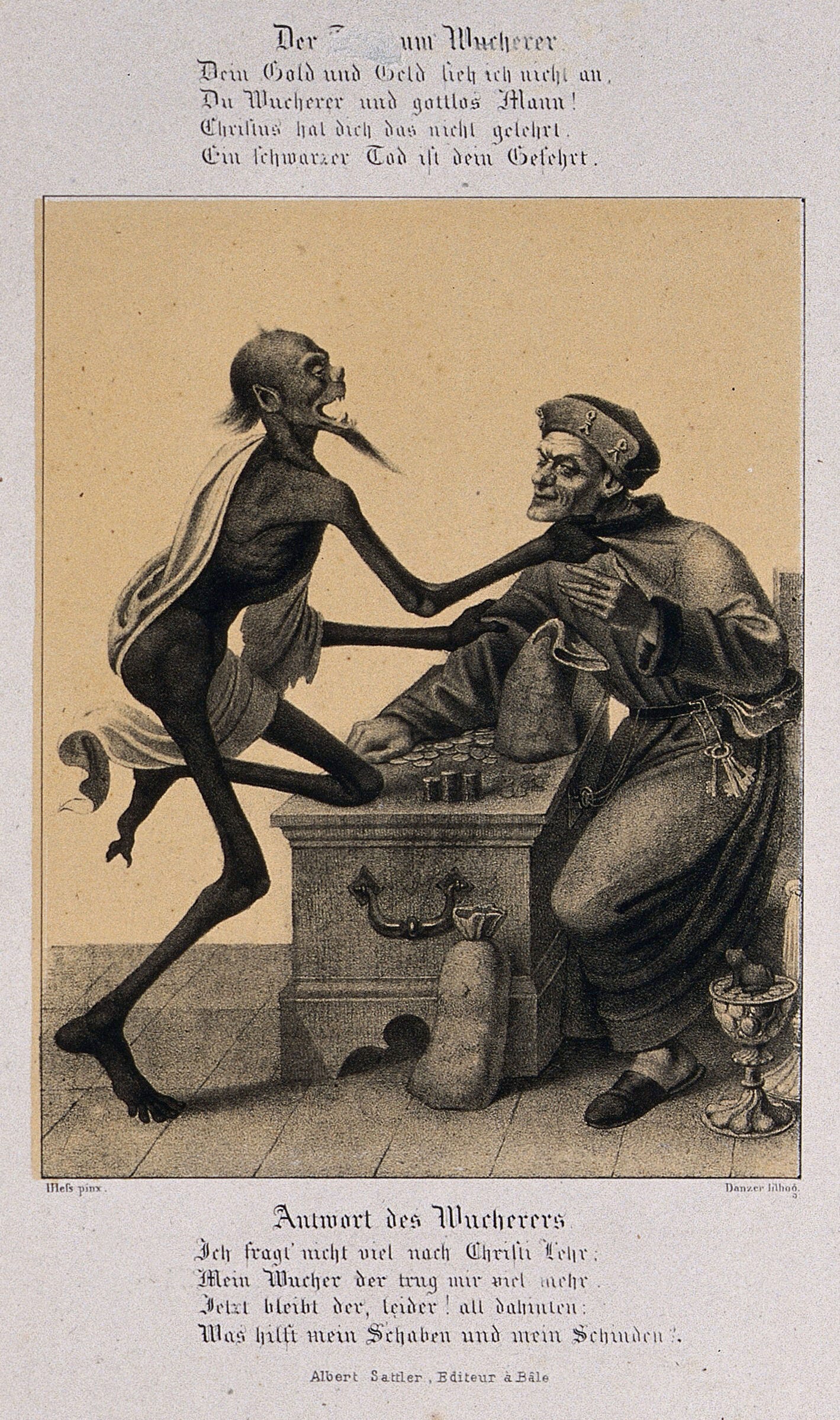

Creditors and lenders have historically been portrayed as evil

On the flip side, moneylenders in the Catholic church are detested and seen as destined for Hell. These frescoes in a cloister show how usurers cavort with the devil. No wonder Jesus converted them into his disciples and showed mercy to one of the most abhorred professions!

Second Circle: The principle of violence

According to Graeber, the second moral confusion around debt is the nature of violence that it engenders. This violence is what he calls the impersonal arithmetic conversion of social obligations. This means that a creditor can numerically quantify how much the debtor owes.

Why is this violent? This enables financial obligations to be impersonal and transferable erasing any form of negotiation between two parties that respect their needs, wants, and capacities. The transformation of obligations into spreadsheets and accounting columns meant we were using the language of debt to simplify human relations.

The problem is, the moment one starts framing things in terms of debt, people will inevitably start asking who really owes what to whom. (8)

This is what Graeber points out as the initial form of violence that would shape how we form our moral beliefs of what is right and wrong.

Twin Circles Conjoined: Debt Today

This language of debt and moral beliefs around it would be elevated at the institutional level and the way the modern nation-state practices capitalism (okay, democracy too). This is where Graeber’s advocacy on debt forgiveness or cancellation comes in. In most of his examples, he highlights debt relations between conquered countries and European nations turning colonial relations into debt indenture. One egregious example is the cost of war and infrastructure charged to the citizens of Madagascar.

The Haitian Independence Debt that began in 1806 is an example of colonial violence converted into financial debt (150 million francs then) as forced compensation for the loss of income from plantation-based slavery. The country borrowed from French banks, defaulted on their loans, and generated a cycle of indenture brought by compounding interest that was fully repaid by 1947. The interest rates were calculated anywhere between 17 to 28 billion euros today.

It was not enough that the blame lay on the French as the Americans occupied Haiti for 19 years further fuelling the devastation brought about by French debt. Graber asks, are these loans? Or is it tribute? putting the US right at the heart of IMF (International Monetary Fund) and World Bank loan policies funding dictators.

If you feel that bank loans (even at the state level) must be paid, Graeber asks, perhaps it is time we start to question why we feel this way and where it comes from.

And so it begins.

Round-Up

Graeber untangles our present economic crises by looking at how we construct the concept of debt on different time and social scales, ranging from social to institutional and state levels. Across these various human arrangements, one thing seems to be at the core:

Why are we compelled to repay a debt?

He proposes two bases on what compels debts to be repaid:

Social obligations built around debt repayment as a moral good

Implicit violence on debtors on two levels:

intimate violence - conversion of social negotiations into impersonal and quantified transactions

institutional violence - conversion of colonial power into the language of financial debt at the state level

He demonstrates how the compounding interest of debt has impacted and created low-income countries today.

Melanie advocates for deep learning through slow reading a difficult book or two per year. I’ve decided to have an in-person meet-up for the Slow Readers this January and build a community. Register now. See you!