Chapter 6 (Part 6) Games with Sex and Death, Debt The First 5,000 Years by David Graeber

How the slave trade entrenched the violent equivalence of money and people

Graeber puts forward two interesting questions in this chapter:

When did people use the language of debt to refer to human relations?

How did the non-substitution clause between money and people transform into full equivalence?

For the last three weeks or so, we have been trying to answer these questions. The examples from small communities like the Lele and the Tiv point to fascinating answers:

Commodity money transactions (one-to-one exchange and valuation) exist alongside social currency transactions (incommensurable exchange between money and people)

Only in extreme situations (inter-village raids and threats of witchcraft/violence) do people become exchangeable with money

The former idea, just like virtual money, first exists in the mind. People were clear about what is a commodity and what is non-tradeable. The way people balance between these two concepts is a work in progress. It was not paradise even in small societies. The Lele and Tiv, though relatively egalitarian and without any hierarchical political structure, exchange females as a measure of equivalence/non-equivalence. They are a patriarchal society even if they follow matrilineal tracing of belongingness.

Today’s post examines how commercial transactions became prevalent in what was once a secondary preoccupation in small societies like the Tiv. Graeber attributes this to the violence of slavery. Though it is clear that commercial valuation and trading predate 19th-century slavery, there is something specific about that upheaval that impacted the language of debt among the Tiv.

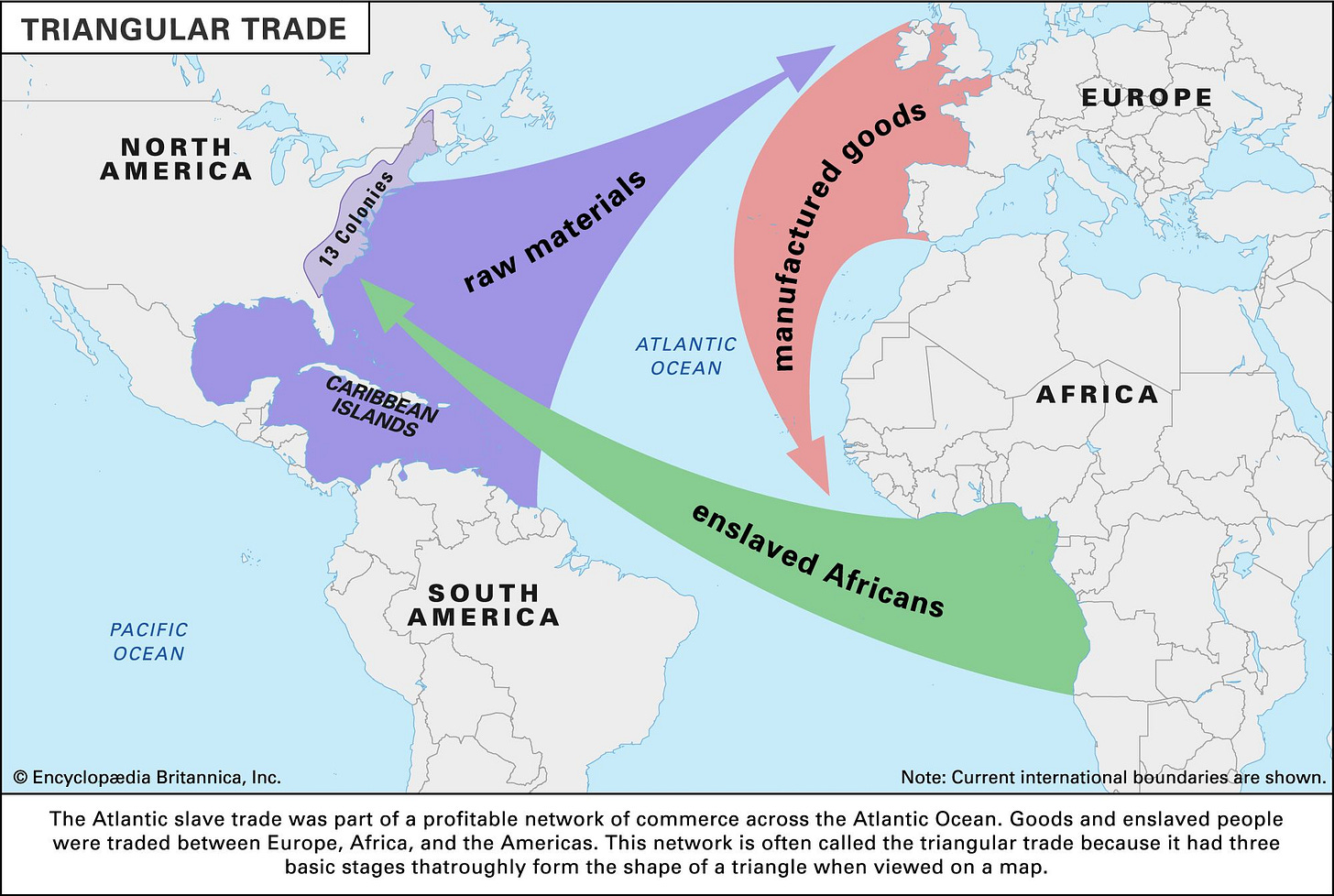

Money for People: the Atlantic Slave Trade

The commodification of people is a mixed process. Shipowners based in Liverpool and Bristol would aggregate valuable commodities like textiles from Lancashire and Yorkshire, copper and brass from Staffordshire and Chesire (the valued social currency among the Lele and Tiv), and guns from Birmingham.

These goods would reach the African port cities like Calabar on the coast of Nigeria.

The port of Calabar with direct access from the Niger River into Tiv land used copper bars as the main currency for the valuation of goods. Graeber found an entry of a merchant ship called Dragon who in 1698 set exchange values.

Though these goods had a currency value, much of the transactions were in the form of credit awarded to African agents who would take them upriver. Since these trades were highly insecure and uncertain, European merchants demanded collateral in the form of human pawns as payment security.

First step: the bastardisation of pawnship

It is not a coincidence that foreign re-interpretations of local and similar arrangements trapped local populations into untenable arrangements such as debt slavery. It is easy to see how the idea of European captains holding pawns as a guarantee for payments transfers effortlessly when the locals understood women pawns and their children as interest-bearing assets. These debt peons worked in the creditor’s household until full payment. Their labour stood for monetary interest until full payment was made.

These debt peons are in a liminal position. They are not slaves from the European or Tiv perspective. They were not separated from their families but they were not necessarily free. European captains who could not wait for payment absconded with their peons. The peons transformation into slaves would be completed.

Second step: the localisation of debt peonage

The African agents copied this model and required pawns as guarantees for payment. In the Dahomey Kingdom (now Benin), West of the Tiv, enslavement quickly became a much expedient and valuable punishment for crime. That includes for the accused family who could be sold as slaves.

It is unsurprising that in the Cross River region, human trading and new definitions of slavery caused untold damage, terror, and chaos. Anyone risked being kidnapped and sold to slavery in the coast. This condition led to the rise of local merchant societies that purported to restore order but merely redirected slavery for their own ends.

One of the more powerful was called the Aro Confederacy, an Igbo group based in Arochukwu. They basically became the local slave traders that profited from a combination of ritual with political power. Their Long Juju Oracle combines both a religious judicial system that exacted punishments through enslavement.

Third step: creating a religious trap for the locals

The rise of these cult societies means that not only do they mete out punishments but they recruit members who misuse these rules to

receive copper bars from selling convicted individuals as slaves

a moneymaking scheme of selling individuals by accusing them of crime

A secret society such as the Ekpe of Calabar accepts members but only by going through nine initiations accompanied by nine laddered payments in copper bars. Run by merchant societies, members

pay fees between 50 - 300 boxes of brass rods per level

use masks, cloth, metal and costumes bought from the merchants

seize a debtor’s communities’ property such as people, animals or goods and when they are usually not enough pressure them to pawn their family members or themselves

The way these politico-magico cult societies work is that it has turned debt and pawnship into:

transforming irredeemable debts of people and social currency (copper or brass bars) into ‘debt cancellation’ by the direct exchange of money for people (slavery)

acquiring socially restricted exchange of social currencies through quick commodity exchanges especially slave trading

The Atlantic slave trade has transformed the language of debt or the non-substitution of people and money into a system where people must strip their humanity to pay a debt indefinitely.

Round-Up

Graeber puts forward an answer to several questions about when and how we have forgotten about the concept of the non-substitution of money with people. He argues that violence, particularly the slave trade, is one specific moment that

shows how small groups like the Tiv come to use the language of debt for social relations

shows how the violence of slavery makes a secondary temporary substitution of people with money a permanent state

This happened in three steps:

The introduction of human pawns by European captains as guarantors and interest bearing assets for goods

The copying of this practice by local merchants and creating these debt relations with religion

Enticing the locals to participate by way of membership and thereby entrench the acquisition of social currency (which now becomes commercial money) and find ways to extract payments through raiding and selling off people into slavery

Though the transformation of social money into commercial money existed prior to the Atlantic slave trade, the legacy of these processes has made sure that ‘money for people’ became permanent conditions.