Chapter 6 (Part 5) Games with Sex and Death, Debt The First 5,000 Years by David Graeber

The paradox of a humane economy: systems of debt that create people are also the means to its destruction

Dear Reader,

I hope that you have been able to follow the sub-arguments of this chapter. We are nearing the end so thank you for your patience. I have been learning more and more about David’s vision of a humane economy with social currencies. However, it seems inevitable that the human condition necessarily involves violence at all levels. This is not paradise at all. The seeds for violence are within human society. Why this is so (or how to avoid it), I’d encourage you to read his other book The Dawn of Everything which tackles this very question of oppression and violence in human organisation.

The language of debt and its possible replacement—care/gift—in government, AI data privacy laws, organ donation, etc. is an interesting turn of the debt language. The switch to gifts and language of care is equally fraught with the same problems. Try practising what you have learned here by looking at this issue. It is also scary to think how much internal violence is concealed.

I love the combination of spring thunderstorms and bright sunny days. Enjoy the contrasts of life. It remains a sweater season which I adore.

Regards,

Melanie

Ideas Integration

Graeber’s project of a humane society consists of two principles:

a social currency that supports the life transformation of individuals (birth, marriage, death)

the incommensurate substitution between money and people

However, unavoidably, paradoxes exist in all forms of human organisations even in acephalous societies or without clear leadership or any formal political structure. You would think that such societies are generally peaceful (and they are on a daily basis). However, we have seen from the Lele in our last post that nonequivalence has a cost.

That cost is the substitution of money for humans (more often, females).

Balance or cancellation comes at the price of blood and slavery. Among the Lele, kidnapping for marriageable wives eases the inequality for young males. By cutting off women from their social context, they can reacquire new relations and roles in their captive village. All it takes is for a village to acquire (legal) personhood. This means the members get together and the village association becomes an entity that can keep wealth, acquire debts, and extract payments through force.

The story of the Tiv beyond the exchange of females for wives also struggles with balance. This gives rise to what the anthropological literature calls a flesh-debt among the Tiv.

Ethnographic Source

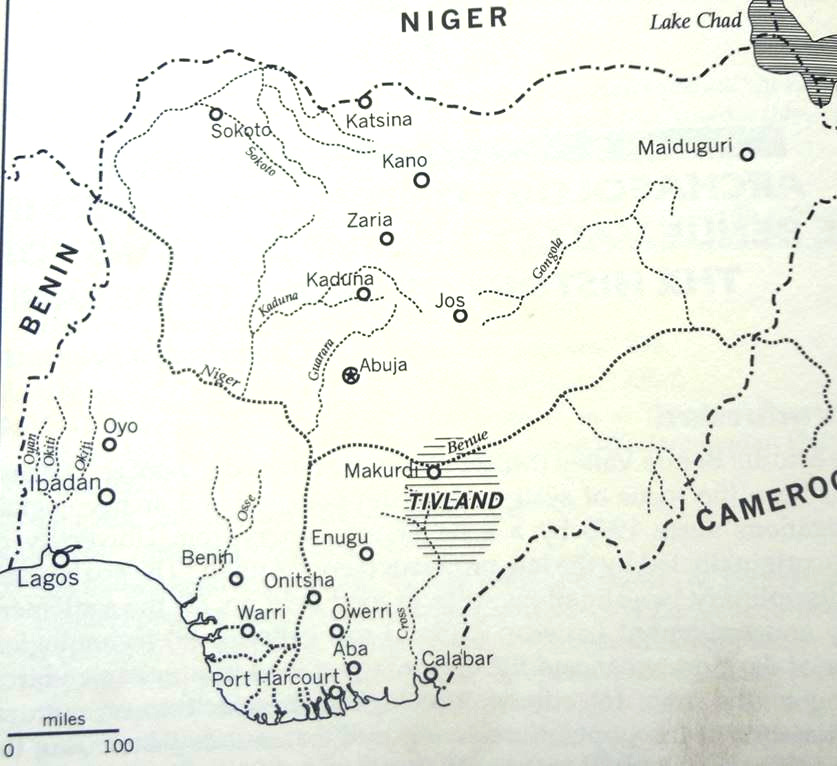

Graeber’s account highlights the ethnographic analysis of the anthropological research of Laura and Paul Bohannan among the Tiv of Nigeria at the tail end of British rule. Similar to Mary Douglas’ work, they documented practices that have ceased since independence in the 1960s such as canoe building.

The Tiv, then numbered 80,000, resided along the Benue River in Central Nigeria. They are a farming community with family residences and compounds enclosed by vegetable gardens. These compounds are situated beside or near their farms. The Tiv are directly in the sphere of the slave trading economy centred in the coastal port of Calabar. Compared to the Lele, the Tiv were exposed to stresses associated with the commercial exchange of money and the slave trade.

When male wealth becomes dangerous

The males control the money that makes the Tiv community go around. These two social currencies are

the tugudu cloth (a long white cloth that may be dyed)

the brass rods for gift and social payments for services (for curing, magic, and religion)

These items are essential to secure marriages and build adult life. Some of its uses include payments for curative and political negotiations, as well as magic and for religious purposes. Though we have outlined previously that these uses are bounded within specific social purposes, aka that these brass rods cannot be used to exchange for wives, there are ways around it.

Men who have charismatic personalities are said to ‘turn chickens into cows.’ They have an abundance of tsav a biological substance that makes them highly influential and can bend another’s will. For instance, an individual may negotiate for brass rods payments for ritual assistance. This innate talent for talking and a ‘strong heart’ results in a quite prosperous life —having a large family. This is significant because, with a ward and female exchange system in place, a man can hold a great number of pawns for any debt exchange. Or retain a high amount of social currency.

This level of success attracts its equal serving of jealousy and social takedown.

It’s called witchcraft.

There is a mbatsav or a society of witches that looks for men to prey on and recruit into their society. Successful politicians in the community are said to be secret cannibals. The witches ensnare their victims by contracting a ‘flesh debt.’ The witches entice an unsuspecting male guest to eat a piece of flesh added to their food surreptitiously. The witches take flesh from a murdered family member. Once ingested, the victim becomes haunted until he offers his relatives one by one to pay off the debt. But the witches’ appetites are insatiable as the target’s social power and stature increase. Only until the victim’s death can finally free himself from this debt.

Of course, cannibalism is likely not a real practice. Rather, the threat of witchcraft is to balance any unexplained power and influence in an acephalous and egalitarian society.

Next week, we’ll look at how the Atlantic slave trade impacted the language of human transactions among the Tiv.

Round-Up

A humane economic system holds a dark side. A non-substitution principle between people and money cannot always hold. The cost is valuing people with money. This paradox balances unequal practices in the community.

This does not only apply to the Lele but also the Tiv.

Social boundaries surrounding the use of social currencies are constantly upended. This time the cost is fear, anxiety, and jealousy which translates into a strong witchcraft cannibal myth.

These fears about being eaten and becoming themselves food as the ultimate debt cancellation have their roots, Graeber argues, to external violence brought about by the slave trade.